Battle of Hastings: Does it matter exactly where it happened?

- Published

- comments

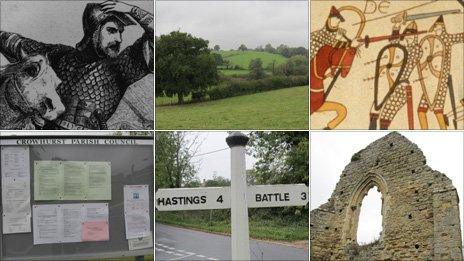

A new book claims King Harold was defeated by William the Conqueror two miles away from the official battlefield. But does the precise location really matter?

As you wander around the fields and lanes of Crowhurst in East Sussex it's not easy to picture one of the bloodiest and most decisive clashes in British history.

The village's cow-nibbled pasture and handsome wisteria-lined cottages seem like they could not be further removed from the carnage and devastation of the Norman conquest - or, indeed, from the tourist clamour that surrounds nearby Battle Abbey, where historians have traditionally believed the English army was routed in 1066.

But according to new research, Crowhurst may have a darker and more violent history than its placid modern-day appearance may suggest.

A book argues that the village and its surrounding fields was the real site of the Battle of Hastings, which placed a foreign ruler on England's throne and, many historians attest, led to the transformation of the national culture and language.

It's a development that appears to have taken Crowhurst by surprise.

Almost a millennium down the line there are few echoes of a more violent past in this settlement of fewer than 900 souls, populated by sturdy family homes with names like Cedar Dale and Badger's Croft, where the parish council noticeboard seems more concerned with the upkeep of the recreation ground and the village hall committee than the military history of the Middle Ages.

Two miles away in the town of Battle, by contrast, it's hard to escape reminders that this has long been thought the site of the clash. Tourists throng towards the visitor centre with its interactive displays. In the grounds of the abbey is a marker at the spot where King Harold was supposedly killed by an arrow in his eye, or ridden down by a Norman knight, depending on your interpretation of the Bayeux Tapestry.

Whether or not Crowhurst really is the true location of the combat zone, Battle is clearly the place indelibly associated with its legacy. And this raises the question of how important it is, if at all, to match known historical events to present-day locations.

For Nick Austin, author of Secrets Of The Norman Invasion, the book which claims Crowhurst as the real Hastings site, accuracy is everything. He insists that without understanding the true topography and layout of the battlefield, historians can never fully gain an insight into events from the past.

"When you know the real site and what was involved in trying to defend it, you get an insight into what was going on in Harold's mind," he says.

"Tourists want to see heritage - that's why they go to Battle Abbey. But they're being misled. The truth is demanding to come out."

Austin believes the Bayeux Tapestry offers clues which show the confrontation took place around Crowhurst. In contrast, English Heritage has maintained that the unusual hillside location of Battle Abbey can only be explained if it was the site of the fighting.

Whichever side is right, Hastings finds itself in good company. There are plenty of examples of hugely important clashes whose exact co-ordinates are the subject of dispute.

The Battle of Bosworth, which proved decisive in bringing the Tudors to the English throne, has been claimed by a number of sites. The exact location of the Battle of Stow on the Wold - the last major skirmish of the English Civil War - has also been widely contested.

And archaeologists have long argued over the whereabouts of significant Roman-era events like the Battle of Mons Graupius, as well as the later Battle of Dun Nechtain, fought in 685 between Picts and Northumbrians.

For this reason, there are those who question whether pinpointing such events is really all that important.

Prof Richard Sharpley of the University of Central Lancashire is an expert in "dark tourism" - visits to sites of death and disaster. He believes that geographical authenticity can be important for locations that have witnessed tragic events relatively recently, such as World War I battlefields where trenches have been carefully preserved.

But in terms of the more distant past, where the landscape displays little obvious trace of what once occurred, he argues the connection is far more nebulous - and, as such, he sees little point in raking over Crowhurst and Battle's rival claims.

"It doesn't matter from a tourist point of view," he says. "You go to a lot of battlefields and there is very little physical evidence left of what happened there.

"You're finding out about it through the visitor centre, not the site itself. The marker becomes the event."

Certainly, whatever the merits of the competing Hastings sites, Crowhurst does not feel like a place expecting to become a major visitor attraction any time soon.

Judging by the posters on the village's lamp-posts, the populace is paying closer attention to the forthcoming jumble sale and Halloween costume party.

In the pub, the Plough, landlady Annette Downey, 36, says locals are intrigued by the claims and are quietly proud of their community's long history. But she adds that few would ever hope to compete with their near-neighbour's tourist infrastructure, built up over centuries.

"Crowhurst's a tiny little place," she says. "Battle will always get the attention. It's been the focus for so long, and I can't really see that changing."

- Published4 August 2010