Haruki Murakami: How a Japanese writer conquered the world

- Published

.jpg)

At midnight in London, and the same time next week in America, bookshops will open their doors to sell Haruki Murakami's latest novel to eager fans. This is not Harry Potter, it's a 1,600-page translation from Japanese. So why the excitement?

When Haruki Murakami's new book, 1Q84, was released in Japanese two years ago, most of the print-run sold out in just one day - the country's largest bookshop, Kinokuniya, sold more than one per minute. A million copies went in the first month.

In France, publishers printed 70,000 copies in August but had to reprint within a week. The book is already on the top 20 list of online booksellers Amazon.com - hence the plans for midnight openings in the UK and across the US from New York to Seattle.

"The last time we did this was for Harry Potter," says Miriam Robinson of Foyles, just one of the bookshops in London opening at midnight for the launch. "It's hard to find a book that merits that kind of an event."

This is the kind of hype that usually surrounds serialised teen literature, says Paul Bogaards of Knopf, the book's US publishers. It is entirely unprecedented in the case of a work translated into English.

The novel has been worked on by two English translators to speed up publication. At 1,600 pages, the book- which will come out in two parts in the UK - is not to be taken lightly.

The book is set in an alternate 1984 - the title plays on the Japanese pronunciation of Q, which is the same as of the number nine. Its two main characters, a male novelist and a female serial killer, exist in parallel universes but are searching for each other as the novel winds its way between their worlds.

Classic Murakami themes are here in the new novel - love and loneliness, alternative and surreal worlds, enigmatic characters and people who seem impassive but are stirred by deep emotions. Not for the first time, questions are raised about free will and cult religion.

"There really isn't anyone like him right now, he is completely different," says Dan Pryce, a member of the sales staff at Waterstone's bookshop in central London, who has been reading the new book in spare moments, in the shop's basement.

"I like the way he never really explains what is happening, he just presents storylines and just lets them flow. Also, there is no real resolution at the end of the book, which leaves you wanting more.

"He does inspire devotion. He goes on and on about his routine and how it bores him to death but he still does it. He is an utter enigma, he is really strange. I think that's what people like about him."

Nostalgia

To date Murakami's work has been translated into 42 languages and appeared on best-selling lists across the world, from South Korea to Australia, Italy, Germany and China.

But Japanese fiction isn't traditionally popular in the West, according to one of the novel's English translators, Harvard professor Jay Rubin. The post-war novelist Yukio Mishima achieved wide acclaim, but nothing on this scale.

Murakami hit the literary mainstream in Japan in 1987 with his fifth book, Norwegian Wood. Named after a Beatles song, it was a nostalgic love story about a group of young people living in a sanatorium in the hills outside Kyoto.

It became a cult classic among young Japanese, selling more than four million copies in Japan alone.

"Norwegian Wood was sort of an experiment for him in writing a novel that was completely realistic," says Philip Gabriel of Arizona University, the other translator who worked on IQ84. It was a commercially-minded novel which avoided the surreal oddities that characterise his earlier and later work.

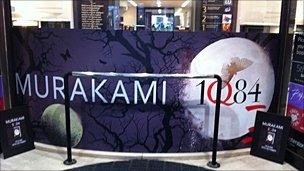

Waterstone's bookshop on Piccadilly prepares to welcome buyers of the new novel

The early novels were not well-received by Japanese critics. "He wrote in a style that the literary establishment found startling and puzzling," says Gabriel.

His scorn for Japanese literary tradition, his conversational writing style, and constant references to Western culture were seen as an assault on Japanese literary conventions. Writers such as Nobel laureate Kenzaburo Oe, initially branded him as a lightweight pop talent.

But as Philip Gabriel puts it: "His early works capture the spirit of his generation - the lack of focus and ennui of the post-Student Movement age."

Though Murakami's books are set in Japan, his subjects of loneliness, boredom and loss, have significance for readers anywhere.

"You don't go to Murakami for views of society but of the human brain," says Jay Rubin.

Anna Zielinska-Elliott, Murakami's Polish translator, who teaches Japanese literature at Boston University, says Polish readers of Norwegian Wood started out looking for "some sort of Japanese myth" but quickly began to appreciate him in a different way.

"If you look at the titles of reviews of his work in the early years, some have some mentions of cherry blossoms and other Japanese stereotypes and gradually over time they disappear.

"He was the first Japanese author who broke through these Orientalist expectations that the readers have. They stopped perceiving him as a Japanese author."

Murakami had a hard time getting Norwegian Wood translated into English, the full translation appearing only in 2000. But his books have now sold 2.5 million copies in the US alone.

Virtual recluse

In Japan, Murakami was adamant not to release any of the details of IQ84 before it launched, only the title and release date. But fans have been posting their own English translations on the internet for a while, prompting the publishers to release the first chapter on the Murakami Facebook page.

According to Knopf, pre-sales of hard copies in the US overwhelmingly outnumber digital pre-sales by 70% to 30%. The inverse is typical for most books, showing how keen Murakami's readers are to hold the physical volume in their hand.

Murakami's status as a virtual recluse has no doubt helped to build his cult following. His opinion on public affairs is constantly sought by the media, yet he gives few interviews.

In June, in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, he spoke out against nuclear power, and his words were reported widely in the Japanese media.

His main channel for communicating his opinion on the state of the world, remains his books.

His last long-form novel, Kafka on the Shore, was released six years ago with a print run of 30,000 books in the US. 1Q84's first print run is three times that, at 95,000.

Philip Gabriel sees him as the quintessential modern writer, one who speaks to a truly globalised world.

"Some novels are too tied in with the shared culture of a nation to be easily appreciated in translation. Murakami's are mostly the opposite."

Listen to Roland Kelts, author of Japanamerica, discussing Murakami on the BBC World Service on 18 and 19 October. Scheduling details here.