Eight radical solutions to the housing crisis

- Published

- comments

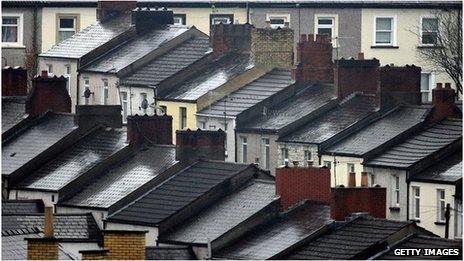

Pressure to address the UK's housing crisis grows ever stronger, with a number of radical solutions being put forward to ease the strain.

Hardly a week goes by without some idea making the headlines. On Tuesday, the left-leaning IPPR think tank publishes a report on how to pay for new house building, external, which includes local authorities investing their own pension pots and freeing up their own land for developers in return for an equity stake. Researchers also think the government should focus more on bricks and mortar than housing benefit.

Last week, a charity suggested encouraging elderly people to move out of their big houses to make room for larger families.

Just 134,000 new homes were built in the UK in 2010, the lowest number since World War II. This is despite 230,000 new households being formed every year. By 2025 there will be a housing shortfall of 750,000 in England alone, according to the IPPR.

The shortage is hitting the younger generation hardest. A fifth of 18-to-34-year-olds has been forced to live with their parents because they can't afford to rent or buy a home, according to the charity Shelter.

Commentators across the political spectrum agree the country faces a growing crisis but there is no consensus on how to fix the problem. Here are some of the boldest remedies being prescribed.

Encourage the elderly out of big houses

Campaigners say single people should also move out of large homes

One solution is to free up family housing by offering elderly people tax breaks to move into smaller homes, says one pressure group. The Intergenerational Foundation says more than a third of the housing stock is under-occupied, which means they have at least two spare bedrooms.

More than half of the over 65s fall into this category and as a result are "hoarding housing", the charity argues. They say the elderly should be given tax incentives to downsize, and the government should also make sure there is more suitable housing for the elderly.

Many would argue that people who have worked hard to buy their own home can live in whatever sized house they want. Some of them say it is not just the elderly who live in houses that are too big for them. Guardian columnist George Monbiot says people who live alone in large houses should lose the 25% council tax discount available to single people.

Television property show presenter Kirstie Allsopp says it is not fair to pick on the elderly as they usually want to hang on to their homes for their children's sake.

"It's not house hoarding. This is their home," she says. "A lot of that generation have done far more in life and taken far less than we have."

Freestyle planning

The government's proposed reform of the planning laws in England has generated much debate and attracted the anger of many groups, including the National Trust and the Campaign to Protect Rural England. Ministers want councils to adopt a "presumption in favour of sustainable development", making it harder for officials to reject proposals.

Proposed changes to the planning laws have raised concerns about Britain's green belt

Steve Turner, a spokesman for the Home Builders Federation, says the planning system has been an obstacle for growth for years. "For decades the planning system has not been delivering enough land to meet the housing needs of our population," he says.

Alex Morton, research fellow at the right-leaning Policy Exchange think tank, says the answer is to reduce the cost of land by freeing up areas for development. "We must shake up our out-of-date planning system, which was designed for the government run-society of the 1940s," he says.

Land costs alone are between about £30,000 and £60,000 per home, he says. Not only does this price people out of the market, it means there is little money left for good quality design and construction. His alternative system would see planners as private consultants working with developers to deliver realistic proposals, rather than working in the public sector stopping development. It would be up to the local community to decide if the proposal was up to scratch.

But planners warn that such an approach is a recipe for disaster. "Whether you are buying a house or building a factory, you want a level of comfort about what can be built on your doorstep," says Richard Blythe, head of policy at the Royal Town Planning Institute.

"The planning system provides this by balancing economic, social and environmental considerations and by enabling democratic input into what is proposed."

Contain population growth

The number of households in England, external is projected to increase from 21.7m in 2008 to 27.5m by 2033, an increase of 5.8m or 27%. Over the same period, figures are projected to rise from 1.3m to 1.6m in Wales, external, and from 688,700 to 880,400 in Northern Ireland, external. The number of households in Scotland, external is projected to rise from 2.3m to 2.8m between 2008 and 2033 - an increase of 21%.

Demand for housing is set to rise

"There's been a remarkable silence on the impact of migration on housing demand," says Sir Andrew Green, chairman of Migration Watch.

Citing the government's figures, he argues that more than a third of new households in England in the next 25 years will be the result of immigration. Even if housebuilding were to increase by 25%, there would still be a shortage of 800,000 homes by 2033, the organisation claims.

"It's a third of the whole issue and no-one's talking about it," he adds. He believes it is possible to bring immigration down to David Cameron's target of "tens of thousands", but it will probably take two Parliaments rather than one to achieve.

But Monbiot says it's neither a practical nor humane way to deal with the problem. "It would be foolish to deny that immigration contributes to housing pressures," he says. "But to say we could solve this through controlling the population - that's the hardest way of doing it. And I'd be very reluctant to take this out on immigrants."

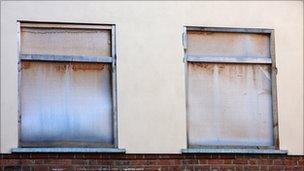

Force landlords to sell or let empty properties

There are nearly one million empty homes in the UK, and 350,000 of them have been empty for more than six months.

Owners keep properties empty for various reasons

Turning them into liveable homes could make a massive difference, says David Ireland, chief executive of the Empty Homes Agency. "If you could suddenly build 350,000 homes you wouldn't sniff at that. So those empty properties are worth having."

The last government brought in orders allowing councils to force landlords to bring empty dwellings back into use, but only 60 have been issued.

It's time for bolder measures, Ireland argues. A significant number of the empty homes are publicly owned.

The answer is to give people the right to buy or rent. They would be given reduced rent in return for doing up the property and their proposal would be overseen by an independent tribunal.

There are various reasons why landlords do not sell or let empty houses, such as property speculation and tax savings. There is zero VAT on building new homes,, external while converting or renovating properties attracts only a reduced rate. The main reason why properties lie empty is that landlords can't afford to do them up, says Ireland, and the answer to this would be to offer a loan to anyone wanting to refurbish them.

Ban second homes

In some parts of Britain holiday homes account for a substantial proportion of the housing stock. About one in 20 households across Cornwall , externalis a second home and owners receive a council tax discount. There's a fundamental unfairness in the fact that there's no penalty on owning a second home, says Monbiot.

About 13,500 properties in Cornwall are second homes

"Why are they doing this? We should be rewarding social good."

The electoral roll makes it easy to work out whether someone owns two homes because you can usually only register to vote in one place. You would have to spend about the same amount of time in your second home if you wanted to register to vote in that area as well, according to the Electoral Commission., external

Local authorities should increase council tax on those with a second or third home, Monbiot says.

But TV property presenter Sarah Beeny says second homes are not responsible for the housing crisis and banning them is "quite extreme".

"It doesn't fall that far from banning people from having a second child," she says. "Maybe make a second home less appealing, but the tax benefits are not there already. Owning a second home is better in theory than in practice."

Guarantee mortgage payments

In these difficult economic times, a lack of mortgage availability is the short-term constraint on development, say house builders.

"If people can't buy, builders can't build," says Steve Turner from the Home Builders Federation.

Most first-time buyers need a large deposit to buy a home

Ways need to be found to encourage mortgage lenders to lend on terms that people can afford, he argues. The best way of doing this is for the government, house builders and mortgage lenders to club together to fund an insurance scheme that would underwrite mortgages where the lender defaults. Talks are in progress but these are complex negotiations, he admits.

But mortgage lenders are risk-averse and have imposed stricter lending criteria for obvious reasons. The first global financial crisis in 2007 was precipitated by the collapse of the sub-prime mortgage market in the US, where banks give high-risk loans to people with poor credit histories.

"Forget the nonsense about the 'mortgage drought'," says Alex Morton from the Policy Exchange. The real problem is not so much lack of finance for mortgages but the impact of high land costs, he argues.

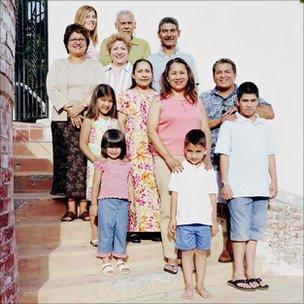

Live with extended family

The general trend is for more people to live on their own rather than with a big family. But in southern European countries, such as Italy, it is much more common for families to live cheek-by-jowl.

It is not always one big happy family when generations move in together

By following this model of grandparents, children and grandchildren all living under one roof, the housing stock would be more efficiently distributed. In 2008 the Skipton Building Society predicted numbers following this model would triple over the following 20 years from 75,000 to 200,000 people.

Several generations often have no choice but to squeeze into the one home to keep costs down. And the UK has its own "boomerang" generation, where young people have to move back home because they cannot afford to get on the property ladder. But where there is a choice, most people would prefer a more private and comfortable living arrangement.

Living with your family can create stress between the generations. The arts journalist Cosmo Landesman wrote in the Daily Mail, external of his experience of moving back in with his parents.

"We tend to sentimentalise the old, to see them as sweet lovable dears," he wrote. "But most people have no idea just how irritating, how utterly exasperating it is, living with two old people."

Build more council homes

Council homes have been part of British society for more than a century, from the "homes for heroes" cottages that were built in the wake of World War I to the much-maligned, monolithic high rises of the 60s and 70s.

New houses in Maidstone, Kent, in 1957

But the "right-to-buy" phenomenon, started by Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government in 1979, led to a massive depletion in council housing stock, with more than two million tenants taking advantage of the scheme.

And the building of council houses to let has almost died off, sending waiting lists through the roof.

Government figures show , externalnearly 168,000 local authority homes were built across the UK in 1950, 88,530 in 1980 and 17,710 in 1990. In 2000, just 280 were built and in 2010, the figure was 1,320.

Since 1990, the building of "social" housing has been mainly the preserve of housing associations, and since that year, they have built an average of 27,000 homes a year.

Abigail Davies, assistant director of policy and practice at the Chartered Institute of Housing, says there is a high demand for social housing across the UK.

"If you look at waiting lists, although a pretty crude measure, they are much higher and longer than could ever be matched by the turnover."

While building more affordable homes is always desirable, it will not solve the housing crisis on its own, she says. Davies believes the most radical solution involves making market prices come down and stay down.

"People often hark back to the 1960s when the state was paying for council houses to be built. I cannot see that happening again with all the other demands on its finances."

Additional reporting: Caroline McClatchey