The only living master of a dying martial art

- Published

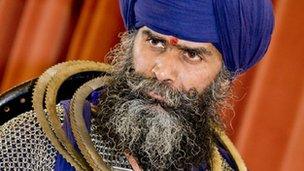

A former factory worker from the British Midlands may be the last living master of the centuries-old Sikh battlefield art of shastar vidya. The father of four is now engaged in a full-time search for a successor.

The basis of shastar vidya, the "science of weapons" is a five-step movement: advance on the opponent, hit his flank, deflect incoming blows, take a commanding position and strike.

It was developed by Sikhs in the 17th Century as the young religion came under attack from hostile Muslim and Hindu neighbours, and has been known to a dwindling band since the British forced Sikhs to give up arms in the 19th Century.

Nidar Singh, a 44-year-old former food packer from Wolverhampton, is now thought to be the only remaining master. He has many students, but shastar vidya takes years to learn and a commitment in time and energy that doesn't suit modern lifestyles.

"I've travelled all over India and I have spoken to many elders, this is basically a last-ditch attempt to flush someone out because if I die with it, it is all gone."

Mr Singh is searching India and Pakistan for a young successor

He would be overjoyed to discover an existing master somewhere in India, or to find a talented young student determined to dedicate his life to the art.

Until he was 17 years old, he knew little of his Sikh heritage. His family were not religious - he wore his hair short and dressed like any British teenager. He was a keen wrestler, but knew nothing of martial arts.

He spent his childhood between Punjab and Wolverhampton and it was on one of these trips to see an aunt in India that he met Baba Mohinder Singh, the old man who was to become his master.

Already in his early 80s, Baba Mohinder Singh had abandoned life as a hermit in a final effort to find someone to pass on his knowledge to.

"When he saw my physique he looked at me, even though I was clean-shaven and he asked me: 'Do you want to learn how to fight'," recalls Nidar Singh. "I couldn't say no."

On his first day of training, the frail old man handed him a stick and instructed Mr Singh to hit him. When he tried, the master threw him around like a rag doll.

"He was a frail old man chucking me about and I couldn't touch him," he says. "That definitely impressed me."

Open-minded

Mr Singh spent the next 11 years on his aunt's farm, milking the buffalos in the morning and spending every day training with his master.

In 1995 he returned to Britain to get married and took work packing food in a factory. He began to teach shastar vidya and immersed himself in research on early Sikh military history.

Soon he had enough interest from students to go into teaching full-time. He now travels around the UK to teach classes and to Canada and Germany where eager students have asked him to share his knowledge.

"The people who are here are open-minded," he says. "I have Muslims and Christians here as well as Sikhs."

But even his most advanced pupils have only recently reached the stage where they can fight him with weapons without getting hurt.

Shastar vidya often gets confused with Gatka, a stick-fighting technique that was developed during British occupation of Punjab and was widely practised among Sikh soldiers in the British army.

Though it is a highly skilled art it was developed for exhibition rather than mortal combat. It is much easier to practise in public.

By working to revive a culture and practice that left the mainstream more than 200 years ago, Mr Singh has come up against a lot of resistance from within the Sikh community.

He says he received 84 death threats in his first two years as a teacher, from other Sikh groups who disagree with the ideology of shastar vidya and the beliefs of the small Nihang sect, which he identifies with.

"It is not just martial technique, there is a lot of oral tradition and linguistic skills that has to be there as well," he explains.

Nihangs still maintain some tenets of the Hindu faith, they have three scriptures rather than one and these extra books contain influences from Hinduism.

Many Nihangs also eat meat and drink alcohol which orthodox Sikhs disagree with. Traditionally they also drank bhang, an infusion of cannabis, to get closer to God.

"Sikhism has gone through several stages of evolution," says Christopher Shackle, a former professor of South Asian studies at Soas, University of London. "When the Nihangs were formed at the end of the 17th Century they were a very powerful group but they became rather marginalised."

An Akali Nihang soldier in 1865

When the Sikhs established their own kingdom under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, he realised he needed a modern army to keep the British out, and he hired ex-Napoleonic officers to train up his soldiers, sidelining the Nihangs.

The Nihangs were further isolated when the British Raj defeated the Sikh state in 1849 and forced Sikhs to give up arms.

"The British introduced a shoot-to-kill policy," says weapons collector and historian Davinder Toor, adding that accounts of British army officers show some troops fired on any man with a blue turban and a firearm.

"There is a sense that the Nihangs got left behind by time," says Mr Shackle.

Mr Singh spends a lot of time travelling to India and Pakistan researching the art, searching for descendents of the Akali Nihang and adding to his vast collection of weapons.

So far he has only met four people who could claim to be masters, now all dead. The last of these, Ram Singh, whom he met in 1998, died four years later.

"Nidar Singh is like someone who has walked straight out of the 18th Century," says Parmjit Singh, who has worked on several books on Nihang culture with the master.

"He is like a window into the past."

He is also still hoping to be a door to the future, opening up the path for new practitioners of the art to follow.

The Last Sikh Warrior was broadcast on Heart and Soul from the BBC World Service. Listen via iPlayer or download, external the podcast.