Spitfire redux: The WWII guns firing after 70 years buried in peat

- Published

- comments

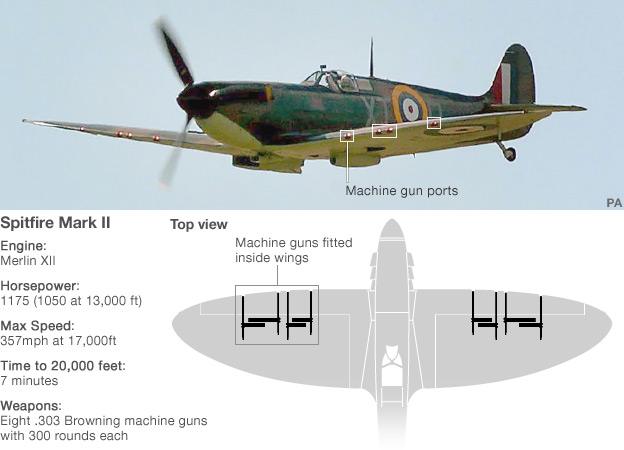

An excavation at the site of a 1941 Spitfire crash in a bog in the Irish Republic uncovered huge, remarkably preserved chunks of plane and six Browning machine guns. After 70 years buried in peat could they be made to fire? They certainly could, writes Dan Snow.

It was June in Donegal, when we stood on a windswept hillside in hard hats and high-vis surrounded by a crowd of locals and watched by an Irish army unit while we filmed an archaeological excavation.

This was the place where, in 1941, Roland "Bud" Wolfe, an American pilot flying a British RAF Spitfire, paid for by a wealthy Canadian industrialist, had experienced engine failure while flying over the neutral Republic of Ireland.

After flying a sortie over the Atlantic, Wolfe was on his way back to his base in Northern Ireland when he was forced to bail out. He parachuted safely to the ground - his plane smashed into the boggy hillside.

Fast-forwarding 70 years and local aviation expert Johnny McNee was able to identify the wreck site. The ensuing dig was accompanied by intense anticipation.

TV historian Dan Snow test fires a machine gun from a WW2 Spitfire which has been recovered from a peat bog in Donegal.

We did not have to wait long for results. Suddenly the fresh Donegal air was tainted with the tang of aviation fuel.

Minutes later the mechanical digger's bucket struck metal. We leapt into the pit to continue by hand. One by one the Spitfire's Browning machine guns were hauled out.

We had hoped for one in reasonable condition - we got six, in great shape, with belts containing hundreds of gleaming .303 rounds. The Irish soldiers then stepped in. This was a cache of heavy weapons, however historic they might be.

Next came fuselage, twisted but in huge pieces, over a metre across, still painted in wartime colours, with neat stencils of the plane's ID and the iconic RAF bullseye-style roundel.

Despite hitting the ground at well over 300mph the artefacts were incredibly well-preserved. The wheel under the Spitfire's tail emerged fully inflated, the paper service manual, a first aid kit with bandages and dressings, the instrument panel, the harness that Wolfe had torn off as he hurled himself out of the cockpit and my highlight - Wolfe's leather flying helmet.

Perhaps 20m down was the magnificent Rolls Royce Merlin engine, which the digger raised to a cheer from the crowd.

Thanks to the soft peat, the inaccessibility of the crash site and the crater rapidly filling with water, a huge number of artefacts had survived the crash with the authorities unable to clear them up.

But Wolfe's Spitfire had more surprises for us.

Thanks to a "wild idea" from Lt Colonel Dave Sexton, ordnance technical officer in the Irish army, it was decided an attempt would be made to fire one of the Browning guns that had spent 70 years in the bog.

His team painstakingly cleaned the weapons and straightened pieces bent by the impact. Finally, on Tuesday we were able to stand on an old British Army range just north of Athlone for the big day.

The machine guns looked as good as new. Soil conditions were perfect for preservation. Beneath the peat there had been a layer of clay. Clay is anaerobic, it forms an airtight seal around all the parts, so there is no oxygen, which limits corrosion.

Had they been in sandy soil, which lets in water and air, the metal would have been heavily corroded.

Rolls Royce Merlin engine: One careful owner, slightly worn

The Irish specialists had chosen the best preserved body and added parts from all six guns, like the breech block and the spring, to assemble one that they thought would fire. They made the decision to use modern bullets, to reduce the risk of jamming.

Wearing helmet, ear protection and body armour I crouched in a trench a metre away from the Browning, which I would operate remotely.

Every part of the gun, to the tiniest pin, had been under a peat bog for 70 years, to the month.

This Spitfire had seen service during Britain's darkest days and is reliably credited with shooting down a German bomber off the Norfolk coast in early 1941. The Irish had found large amounts of carbon inside the weapon, evidence of heavy use.

I turned the handle of the remote firing mechanism. The Browning roared, the belt of ammunition disappeared, the spent shell cases were spat out and the muzzle flash stood out sharply against a grey sky. It was elating.

That was the noise that filled the air during the Battle of Britain.

The gun fired without a hitch. There can be no greater testament to the machinists and engineers in UK factories in the 1940s who, despite churning out guns at the rate of thousands per month, made each one of such high quality that they could survive a plane crash and 70 years underground and still fire like the day they were made.

During the course of the war, one firm, Birmingham Small Arms (BSA), produced nearly 500,000 Browning guns. All this was despite being targeted by the Luftwaffe. In November 1940, 53 employees were killed and 89 injured.

The firing was yet more evidence that the Spitfire, with its elliptical wing shape, engine and machine guns, is one of the crowning achievements in the history of British manufacturing.

The machine guns will now be made safe and join the rest of the aircraft on permanent display in Londonderry, where Wolfe was based, a city on the edge of Europe that played a pivotal role in the war.

The excavation of Bud Wolfe's plane is part of Dig WWII, a series for BBC Northern Ireland by 360 Production to be presented by Dan Snow and due to be shown next year.