Penn State: Would you do better than Joe Paterno?

- Published

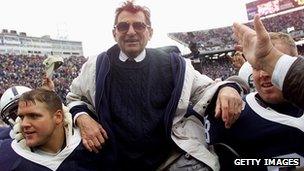

Joe Paterno watches his team practise. He would be sacked later that night

The author, a Pennsylvania State University graduate, wonders how her alma mater could find itself in the centre of a horrific sexual abuse scandal. The answer: very easily.

This week, the office of Pennsylvania's attorney general released a damning grand jury report. It outlined years of sexual abuse allegedly perpetrated by former Penn State assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky.

Though Mr Sandusky had retired from the university in 1999, the report alleges that he raped and molested boys on Penn State's main campus for the next several years.

The report also included details of witnesses seeing the abuse and declining to call the police. There were allegations of school officials, amongst them long-time football coach Joe Paterno, receiving evidence of abuse and declining to take serious action.

The shocking behaviour did not end there: President Graham Spanier, who has since lost his job, offered his full-throated support for two university officials accused of covering up the abuse.

Then, after the board of trustees voted to fire both Mr Spanier and Mr Paterno, hundreds of Penn State students took to the streets, demanding the return of their beloved coach.

To the rest of the world, it looked like madness. What on earth was going on at Penn State?

Sadly, what's going on is what always happens in cases like these - only this time, the whole world is watching.

'Unbelievable consequences'

Conservative estimates published in the journal Science, external suggest that 5% to 10% of American boys have been sexually assaulted, as have 20% of girls. Some 90% of these cases are never reported.

These numbers have remained consistent for years. And the Penn State example helps demonstrate why.

"We choose not to talk about it," says Jolie Logan, chief executive of Darkness to Light, a non-profit group that trains adults to prevent abuse. "Who wants to think about people having sex with children? Because it's not comfortable to talk about, we don't."

At Penn State, Mr Paterno's actions have led to a lot of justifiable outrage, along with a lot of less-justifiable claims that anyone else in that position would have done things differently.

"All of us over-estimate our likelihood of being a hero, and the ease with which we would go ahead and do the right thing," says David Finkelhor, director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire. "Faced with the unbelievable consequences that the disclosure might have, their will collapses, and they are unable to do the right thing."

Paterno eventually lost his job for going to the university administration instead of the police with information about an assault. It was a poor decision, but a common one in these types of cases. "People don't know the law. Unless you have campaigns or an awareness program, people go to who they perceive to be the authority, instead of the police," said Lisa Cromer, co-director of the Tulsa Institute for Trauma, Abuse and Neglect.

'Betrayal blindness'

Ms Cromer has conducted 10 years of research on why sexual abuse goes unreported. She notes that men are significantly less likely than women to acknowledge abuse, but that in a tremendous number of cases, witnesses to abuse find ways to rationalise that behaviour.

Joe Paterno was a legendary winner and was revered by players and fans

"Generally speaking, we all under-report," she says. "People think it's a big deal to report - they want to make sure there's no doubt. But really, that's a decision for the authorities and the courts."

Self-preservation, denial and fear are all at play. Some of that stems from conscious decision-making, and some of it may be "betrayal blindness".

Jennifer Freyd, a professor of psychology at the University of Oregon, has been testing this concept, which posits that people who could suffer harm from confronting abuse - physical, professional, or psychological - are often unable to recognise that the abuse exists.

"If you get to the point where you're aware of the abuse, it's hard to avoid that you've detected it," she says.

"A better strategy, if you're lucky enough to be built this way, is to just not see it in the first place. This can get a lot of people in trouble."

A hopeful riot

Psychological rationales do not let the Penn State officials off the hook. But they do suggest that the factors allowing sexual abuse are not unique to the university.

To open one's mind to the realities of sexual abuse - that it happens all around us, that good people are complicit, that not enough is being done to stop it - can be too intimidating, says Ms Freyd. She says the denial displayed by the protesters makes sense in this context.

"Once you really look at it, you feel you need to do something about it. It's taking on an awfully big responsibility. A lot of people who are responding to this situation may not be ready to deal with it," she says, especially considering the statistical reality that numerous abuse victims and sexual abuse perpetrators are part of the audience.

To her, the riots, the firings, the nationwide scandal are actually positive signs. Sexual abuse of this magnitude, she says, goes on all the time, but rarely are charges filed, officials held accountable, or outrage expressed. The uproar at Penn State is much better than the alternative: silence.

"Though it's very uncomfortable for everyone, it helps that people are freaked out," says Ms Freyd.

"It's hard to get through the process of becoming aware, but with awareness we're in the position to stop this sort of thing. The more we talk about it, the more it will come to an end."

- Published10 November 2011

- Published8 November 2011