Who, What, Why: Why don't more countries use plastic banknotes?

- Published

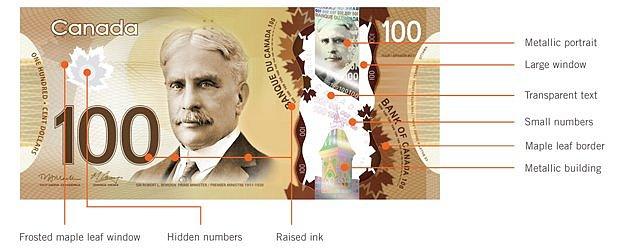

The Bank of Canada began circulating $100 polymer banknotes this week in an effort to combat counterfeiting and reduce costs. So why don't more countries use plastic cash?

On the face of it, plastic banknotes have many advantages.

They last a long time, and they don't get dirty so quickly - a great advantage in countries with hot climates, and sweaty pockets.

"The tropical climate is a challenging environment for banknotes, especially because of high humidity and high temperatures," says polymer researcher Stane Straus.

"This causes paper notes to absorb moisture, thus becoming dirty and limp quickly. Polymer notes, on the other hand, do not absorb moisture.

"You could say that polymer notes beat paper notes in terms of cleanliness and durability in all climates, but this particular advantage of polymer notes stands out even more in tropical climates."

Canada had security, cost and also the environment in mind when it took the decision to go plastic.

When counterfeiting hit a peak in the country from 2001 to 2004, blame was put on the $10 and $5 bills printed in 2001 and 2002, which were deemed to have too few security features.

By this stage, the polymer technology first introduced in Australia in 1988 was already well established, and security features such as transparent windows and microprinted watermarks looked like a solution to Canada's problem.

Canada claims its $100 bill is the world's most advanced banknote, including a hologram within the transparent window. It also shows a circle of numbers that match the value of the denomination when held up to a light.

A $50 polymer denomination will follow in March and a $20 bill in late 2012. By the end of 2013, new $10 and $5 bills will have been introduced, and all Canadian money will be printed on polymer.

Recycling

The new notes, says Bank of Canada senior analyst Julie Girard, will last 2.5 times longer than paper bills. The lifespan of a $20 bill - Canada's most widely circulated denomination - should be at least seven years.

That will save production costs because fewer bills will need to made - and the plastic is also recyclable at the end of its lifetime.

"It's possible that someone could be sitting on a lawn chair some day whose parts are made of currency," Girard says.

Stane Straus also sings the praises of polymer, from an environmental point of view, compared with traditional "paper" banknotes.

Many of these are actually made of cotton - US paper bills are 75% cotton - which, he points out, takes large amounts of pesticides and water to produce.

So why don't more countries cash in on this technology?

Today, 23 countries use polymer banknotes, but only six have converted all denominations into plastic.

Tom Hockenhull, curator of the Modern Money exhibition at the British Museum, says one reason is that the security gap between paper and plastic notes is closing.

It is now possible to make "hybrid notes" - paper notes with a transparent polymer window - he points out.

"Paper is much more secure than it used to be and the new [British] £50 note, for example, has features that are extremely hard to counterfeit," he adds.

Meanwhile counterfeiters are making progress with polymer. "Polymer is very hard to counterfeit, but it hasn't stopped people trying: good imitations do appear from time to time," Mr Hockenhull says.

Risk

He also points to some notable disadvantages of polymer banknotes:

They are harder to fold

They are more slippery, which makes them harder to count by hand

Some less developed countries may not have the facilities to recycle them - and when they burn they pollute the air

In addition, polymer notes cost more to produce in the short-term, which could be a drawback for developing countries. The payback from their extra durability only comes over time.

Another factor could the conservatism of central bankers.

"Central banks are very conservative institutions," Stane Straus says. "People making the decision to convert to polymer - partially or fully - are taking a personal risk.

"Many central banks are simply waiting until others convert and then they will follow."