How can musicians keep playing despite amnesia?

- Published

- comments

Scientists are trying to understand how amnesiacs can lose all memory of their past life - and yet remember music. The answer may be that musical memories are stored in a special part of the brain.

When British conductor and musician Clive Wearing contracted a brain infection in 1985 he was left with a memory span of only 10 seconds.

The infection - herpes encephalitis - left him unable to recognise people he had seen or remember things that had been said just moments earlier.

But despite being acknowledged by doctors as having one of the most severe cases of amnesia ever, his musical ability and much of his musical memory was intact.

Now aged 73, he is still able to read music and play the piano and once even conducted his former choir again.

Now researchers believe they are closer to understanding how musical memory is preserved in some people - even when they can remember almost nothing of their past.

Clive Wearing conducting a choir seven months before his illness

At a Society for Neuroscience meeting in Washington this month, a group of German neurologists described the case of a professional cellist, referred to as PM, who contracted herpes encephalitis virus in 2005.

He was unable to retain even simple information, such as the layout of his apartment.

But Dr Carsten Finke of Charite University Hospital in Berlin says he was "astonished" that the cellist's musical memory was largely intact and that he was still able to play his instrument.

The brain's medial temporal lobes, which are largely destroyed by severe cases of herpes encephalitis are "highly relevant" for remembering things such as facts and how, where and when an event happened.

"But this case and also the Clive Wearing case suggest that musical memory seems to be stored independently of the medial temporal lobes," Dr Finke says.

Musical therapy

He has also studied the case of a Canadian patient who in the 1990s lost all musical memory after having surgery that damaged another part of the brain known as the superior temporal gyrus.

This has led him to conclude that the structures of the brain used for musical memory "might be the superior temporal gyrus or the frontal lobes".

Dr Finke says more research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

"But what is really new in this case is that we could show that in such a severe and dense amnesia there's still an island intact of memory, the musical memory," he says.

Dr Finke thinks it may be possible to use this to improve PM's rehabilitation and that of other amnesiacs.

"It's very interesting to know that in these patients the memory is intact at all, so it could be used as a gateway to these patients. You could think about maybe coupling special music to activities like taking medication.

"They can also do musical therapy, starting to play music again and by doing this gaining some quality of life," he says.

Such techniques should be applicable to both musicians and non-musicians as they share the same memory systems.

"We know that musicians have differently adapted brains - some areas of the brain are larger than in non-musicians, but it's not so easy to think that they develop a new system," he says.

Damaged lobes

Musical memory isn't necessarily the same as other types of memory, says Dr Clare Ramsden a neuro-psychologist with Britain's Brain Injuries Rehabilitation Trust, which is studying the case of three musicians, including Mr Wearing.

Clive Wearing plays well, but he has no memory of having played before

"That's potentially because it isn't just knowledge. It's something you do," Dr Ramsden says.

Different aspects of playing music involve different parts of the brain, she has concluded.

"The research we're doing is starting to show that people with damage to mainly their frontal lobes, their musical skills are affected differently to people like Clive whose medial temporal lobes are damaged.

"Clive can still play and read music, but people with frontal lobe injuries might have difficulty reading and performing a piece of music for the first time, but are better at pieces they already know," Dr Ramsden says.

Prof Alan Baddeley of the University of York, who has written study papers on Mr Wearing, said he was not surprised by the findings of the German team.

"PM's case is a very good example that memory isn't unitary, that there's more than one kind of memory," he said.

"Amnesia doesn't destroy habits, but sufferers do lose the ability to acquire and retain information about new events."

Handel's Messiah

Clive Wearing's wife Deborah has written a book, Forever Today, about how their lives have been affected by his amnesia. She says all his musical skills are still intact.

Clive and Deborah Wearing were married in 1983

"If you give Clive a new piece of music he sight reads it and plays it on the piano, but you can't say he's learnt it," she told the BBC World Service.

But she adds: "Clive has no knowledge of ever having played the piano or whether he still can."

He has lived in specialist residential care since 1992, having spent his first seven years of illness in a secure psychiatric unit.

"Even though he's had a piano in his own room for 26 years he doesn't know it until it's pointed out to him."

Ms Wearing says her husband's performance does improve, when he plays a piece regularly, even though he has no memory of having played the piece or anything else before.

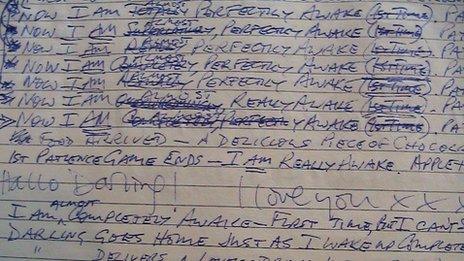

Extract from Clive Wearing's diary in 1990, where he records the moment he woke up over and over again

However, she says he does remember things he has known all his life or performed regularly. "He learnt Handel's Messiah as a child and can still sing it," she says.

She says he remembers her and their mutual love and that music is a wonderful pastime for both of them.

"Music is a place where we can be together normally because while the music's going he's totally himself. He's totally normal.

"When the music stops he falls back into this abyss. He doesn't know anything about his life. He doesn't know anything that's happened to him ever in his life."