HIV/Aids: Why were the campaigns successful in the West?

- Published

The arrival of HIV/Aids in the early 1980s led to predictions of deaths on a massive scale - yet developed countries largely avoided such a fate. What did the wave of urgent awareness campaigns get right?

Under darkened sky, a volcano erupts. Doom-laden images of cascading rocks give way to shots of a tombstone being chiselled.

"There is now a danger that has become a threat to us all," intones the actor John Hurt ominously in a voiceover. "It is a deadly disease and there is no known cure."

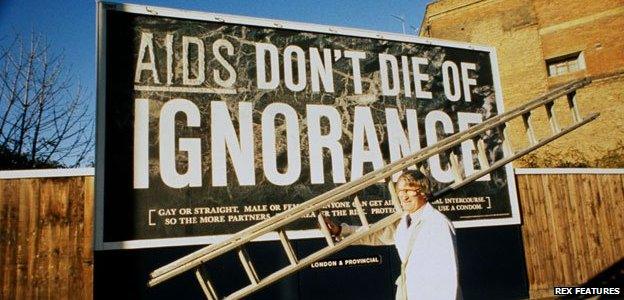

The word etched on to the blackened grave is revealed - Aids. "Don't die of ignorance," runs the slogan.

With its stark, unambiguous warnings ands bleak message, the advert shocked viewers , externalwhen it appeared on British screens in 1986. Immediately, it faced accusations of panic-mongering and complaints that it would terrify any children who happened to be watching.

The idea of the 'Tombstone ad' was to shake a nation into taking charge of its own sexual health

And yet the campaign - the world's first major government-sponsored national Aids awareness drive - would later be hailed as the most successful.

Its tactics were imitated around the world. France, Spain and Italy were all slower to react, the Terrence Higgins Trust (THT) has noted. Each of those countries has around twice the number of people with HIV as the UK, where there were an estimated 86,500 in 2009, according to the trust.

Those figures are in stark contrast to sub-Saharan Africa, where two-thirds of the world's 33.4 million people with HIV live. In the three worst affected countries - Botswana, Swaziland and Zimbabwe - around a third of the population lives with the virus, according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/Aids.

The disparity between rich and poor nations can partially be explained by resources. However, the Department of Health spends £2.9m each year on national HIV prevention in England, part of the £10.6m spent on sexual health promotion in general. By comparison, in 2008 alone some $15.6bn (£10bn) was spent on HIV/Aids prevention around the world, mostly in developing countries.

Early campaigns are widely credited by experts with making the difference in the West by raising awareness and changing behaviour. And yet in the early 1980s, the UK would hardly have seemed an auspicious location for this revolution to begin.

As reports of a new, deadly virus filtered across the Atlantic from the US, British authorities were initially slow to react, argues Sir Nick Partridge, chief executive of the THT, the sexual health charity which was set up in response to the emergence of HIV.

The climate made this unsurprising. Some headlines spoke of a "gay plague". The fact that the groups most at risk were homosexual men and intravenous drug users meant outright hostility from certain quarters.

Between the 1982 Aids-related death of Terry Higgins, who gave the charity its name, and the government's decision to open needle exchanges for addicts in 1985, very little was done to tackle the growing list of fatalities, Sir Nick argues.

"Those three years of people dying seemed a long time," he says.

"There was a huge sense of anger - if Aids had hit any other group in society, there would have been an immediate response."

However, those in authority who wanted to take action had to confront high-level antipathy. The then-Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police, James Anderton, referred to victims "swirling about in a human cesspit of their own making".

Nonetheless, Norman Fowler, now Lord Fowler, then health and social security secretary, and Sir Donald Acheson, the chief medical officer, were convinced that action had to be taken. By the middle of the decade, scientists were predicting that the cumulative total of UK HIV cases could reach 300,000 by 1992 if nothing were done.

"There were people in government and also people in the media who said, 'Why are you spending all this time concerned about gay people and drug addicts?'," Fowler recalls. "But that was a minority view."

As a result of the two men's lobbying, the government's drive against Aids was not run from Downing Street but instead co-ordinated by a cabinet committee chaired by the plain-spoken Tory grandee Willie Whitelaw.

"It was like he was running a VD campaign in the Army," recalls Fowler wryly. "I think it's an advantage it wasn't done at No 10. It wasn't a natural subject for Margaret Thatcher.

"We did it in an extremely pragmatic way. We treated it as a public health issue."

An advertising agency, TBWA, was commissioned to make adverts intended to shock the nation into action.

As well as the tombstone clip, another showed an iceberg which, beneath the surface, bore the legend Aids in giant letters.

The message of both was simple, but apocalyptic - a deadly disease was a threat to everyone, not just the "small groups" who had largely been affected by it so far.

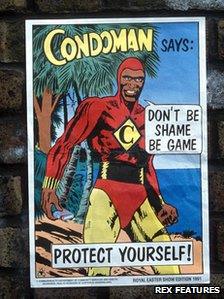

The message correlates masculinity and responsible sexual behaviour

No-one doubted the strategy was bold and attention-grabbing. But all involved were acutely aware of the risks and the potential to backfire.

"It was done with considerable degrees of secrecy," remembers Sir Nick, who was consulted on the campaign. "I had to go to TBWA's entrance at 8pm and go through the goods entrance, such was the degree of political sensitivity.

"There were those who said the adverts increased fear more than understanding. I think they did both. They stopped a lot of people from having any sex at all for quite some time, but one upside was that they got everybody talking about sex and safer sex."

The iceberg and the tombstone were not all there was to the campaign. In addition, a leaflet was sent to every household in the country and a week of educational programming was scheduled at peak time on all four terrestrial channels.

But it was the television adverts which made the longest-lasting impression on the popular consciousness, instilling a sense of doom easily recalled by anyone over the age of 30.

"They were tremendously effective. They were visually so striking," says Dr Sarah Graham of Leicester University, who recently organised an exhibition of Aids poster campaigns. "People had to watch because it was so extreme."

The impact was so immediate that it was widely imitated around the world. Fowler recalls visiting the US in 1987 and discovering to his surprise that there was no national campaign.

"What we found, to our amazement, was the Americans saying, 'What we think we need to do is what you're doing in the UK,'" he remembers.

The British strategy was consequently imitated by other countries, although these varied according to cultural backdrop. For instance, it is difficult to imagine the focus of Australia's campaign, a muscle-bound, prophylactic-wielding superhero named Condoman, receiving official backing in Whitehall.

And in sub-Saharan Africa, the world's worst-hit area, running such an awareness drive is no easy matter. European HIV/Aids advertisements can be text-heavy as a means of getting information across, Dr Graham says. But she says this is simply not possible in national territories where dozens of languages and dialects may be spoken.

Moreover, antipathy from political leaders has prevented such campaigns in the countries which need them most, according to Simon Garfield, author of The End of Innocence: Britain in the Time of Aids.

A 2005 billboard campaign against HIV/Aids outside a university in the Niger Delta

"If you've got a head of state who's saying there isn't enough money and this doesn't happen here anyway, it's hard to make any headway," Garfield adds.

"You are talking about different educational cultures, different sexual cultures. But what you can say is that if there had been anything comparable it would have had a major effect."

For Fowler, however, the issue is not just about variances in national culture. Sexual health, he argues, will invariably be a topic that makes elected leaders unconformable.

Indeed, a House of Lords committee chaired by the peer concluded in August that HIV campaign efforts in the UK at present were "woefully inadequate", that a false sense of security had been allowed to set in and that a new awareness drive was needed.

"It's not a natural area for politicians to be in," Fowler says. "Sometimes religion comes into it, sometimes there are views about gay people. It's undoubtedly controversial and some people don't like being controversial in this area."