Drive-in cinemas: Will they survive the digital age?

- Published

At their peak, there were more than 4,000 drive-in cinemas in the US. Now only a few hundred have survived against the odds - but could the cost of converting to digital be the final straw?

"I would hate to close America's oldest drive-in movie theatre, but it's a matter of personal choice about whether we can afford to spend that kind of money."

Shankweiler's, in Orefield, Pennsylvania, first opened its doors in 1934 but current owners Paul and Susan Geisinger fear the 2012 season may be its last.

Like many small independent cinemas across America, it could be forced out of business by the cost of converting to digital projection.

Mr Geisinger is coming up to retirement age and is not keen on the idea of taking out $175,000 (£112,000) loan to pay for a digital projector and the necessary building work to house it.

"It is a lot of money for a seasonal business. But we have been left with no choice. Either the conversion has to be made or it's going to close," says Mr Geisinger, who started working as a projectionist at Shankweiller's in 1971, before buying the business in 1984.

The big Hollywood studios are eager to eliminate the cost of manufacturing and shipping the 35mm film prints that have traditionally been the mainstay of the industry.

By posting hard drives instead distributors could save hundreds of millions a year, according to some estimates - a tempting prospect for an industry under pressure from internet piracy and video games.

And with more than half the cinema screens in America already converted to digital, experts believe 35mm prints could disappear altogether within two or three years.

The industry says digital leads to a quicker turnover of movies, greater choice for consumers, and the promise of 3D and other special features.

But hundreds of small independent cinemas, in the US and around the world, have already decided they cannot afford to buy the equipment needed, say industry sources.

The death of the drive-in - if that is what is happening - is likely to be felt more keenly in the US than in a country like the UK, where the concept never really got out of first gear.

A generation of Americans spent their formative years - and did their courting - at the drive-in, in an era when the car was king.

At the height of their popularity, in the late 1950s, America had more drive-in movie theatres than indoor screens - more than 4,000 of them. But they declined in the 70s and 80s due to owners cashing in on high land values and the competition of video rentals.

About 400 drive-ins have survived to the present day, most of which are small, family-run concerns in rural areas.

'Passion pits'

Fred Heise took over the Melody Drive-In Theatre, in Knox, Indiana, from his father in the early 1970s, and had hoped to hand the business on to his son, until the digital spectre reared its head.

"We will probably end up doing it. It is one of those where you do it kicking and screaming," the 64-year-old says. "One wonders if you would live long enough to completely pay it off."

Drive-in cinemas have shown resilience to past challenges

Today's drive-ins are a far cry from the so-called teenage "passion pits" of 50s legend - you are more likely to be parked next to a pair of "baby boomers" reliving their youth, or a young family enjoying a cheap night out, than a car full of rowdy or amorous teenagers.

But despite the pervading air of nostalgia, the owners have tried to keep pace with technology.

Patrons can now listen to the movie on their car stereos, on a special FM frequency, rather than through the primitive "sound poles" that sit next to each parking bay.

Drive-ins also try to offer better value than the local multiplex. You can normally watch three or four of the latest Hollywood releases for less than $10 (£6.39) in total, as well as stocking up on popcorn and hot dogs for less than you would pay in one of the major chains.

"For me it's mostly family value. Because I work so much my daughter and I don't get to spend a lot of time together so we come here and we watch the shows," says Michael Ravenscroft, a truck salesman, from Sykesville, Maryland.

'Mesmerised'

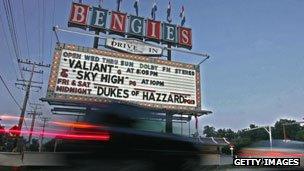

He has been visiting Bengies, Maryland's only remaining drive-in, since he was eight.

Edward D Vogel's pride and joy: An original 1956 projector

Diane Hain, an accountant from Baltimore, is possibly Bengies' number one fan, having visited the theatre 70 times in the past year: "This place is special. I wouldn't know what to do with myself if it was gone."

Fortunately for her, Bengies owner, D Edward Vogel, is among those who plan to make the leap into digital. He is convinced the drive-in is more than just a museum piece.

"Young people, who have the video games and all those fancy toys and those nice phones, they are amazed.

"They come in here and they are mesmerised by this fine old antique I call the Bengies drive-in and that does warm my heart like you would not believe."

Mr Vogel, who bought Bengies from his father more than 20 years ago, is still using the same projection equipment his family installed when they opened the theatre in 1956.

'Scary' time

Maintaining the two vintage projectors, and splicing film together with classic trailers to provide a continuous show for customers, are what he enjoys most about the job and although he believes digital will rob the drive-in of some of its magic, he is in no mood to throw in the towel.

"There is something so special about sunset to me. That moment before twilight. That even when I am not operating, I will look at that screen and my heart pines to put light up there."

Mr Vogel, who is also administrative secretary of the United Drive-In Theatre Owners association, says it is a "scary" time for many of his members.

"You would think the distributors would take special care of the little guy and, truthfully, I don't think they really care. I think they already figure the screen count's going to go down."

Few drive-in owners will go hungry, even if they are forced to shut up shop. Many are sitting on prime real estate and should be able to look forward to a comfortable retirement.

'Retiring to Florida'

They are also reluctant to be seen as standing in the way of progress.

"I have seen digital and it is brilliant," says Steve Wilson, owner of the Holiday Drive-In, in Mitchell, Indiana, but he believes the distributors have pushed the technology on independent operators too quickly, before the price of the hardware has a chance to come down.

And he believes that if drive-ins are allowed to die, the US will lose a little piece of its soul.

Drive-in audiences have changed over the years

"I think it is a big loss to the American people. Everywhere, you see theatres winding down and people are just aghast at what is going on, but they cannot do anything about it."

He will not be among the drive-in owners "retiring to Florida" after "selling their land to Wal-Mart", he is quick to point out, and is currently looking for a job after deciding to get out of the cinema business.

Fewer than 20 drive-in cinemas around the world have so far made the plunge into digital, according to industry experts, and probably no more than four in the US.

But the industry has proved remarkably resilient over the years.

Shankweiler's, which was the second drive-in theatre to open in the US, but may well be the oldest one in the world to have stayed open continuously, even bounced back from being destroyed by a hurricane in the 1950s.

It would be a shame, says Paul Geisinger, if it were to close now.

"I am going to toss a coin and decide what to do," he says. "By September 2012 we will either have converted to digital or will be packing our things into boxes and closing it down."

You get the feeling this particular big screen story may yet have a sequel.