'Cleansed' Libyan town spills its terrible secrets

- Published

The 30,000 people living in a town in northern Libya have been driven out of their homes, in what appears to have been an act of revenge for their role in the three-month siege of the city of Misrata. So what really happened in the town of Tawergha, are the accusations of brutality against the town's residents fair and what does it say about hopes for national unity?

"No, they can never come back… They have done us too much harm, terrible things. We cannot forgive them."

Najia Waks, a young woman from Libya's third largest city, Misrata, is talking about the people of Tawergha, a town about 50km (30 miles) to the south.

For three months between early March and the middle of May, the forces of Muammar Gaddafi laid siege to Misrata. These forces were partly based in Tawergha, and the people of the town are accused of being complicit in the attempt to put down the uprising in the city. They are also accused of crimes including murder, rape and sexual torture.

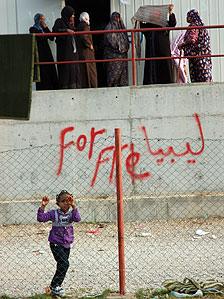

Tawerghans are scattered across Libya in camps

The fighters of Misrata eventually prevailed, breaking out of their battered city, and Misratan brigades made up part of the force that overran the capital Tripoli in August. They also captured and killed Gaddafi and one of his sons in late October, and put the corpses on display in their city.

In the middle of August, between the end of the siege and the killing of Gaddafi, Misratan forces drove out everyone living in Tawergha, a town of 30,000 people. Human rights groups, external have described this as an act of revenge and collective punishment possibly amounting to a crime against humanity.

Tawerghans are mostly descendants of black slaves. They are generally poor, were patronised by the Gaddafi regime and were broadly supporters of his regime. Some signed up to fight for him as the regime fought for its survival.

What happened in Misrata and Tawergha revealed one of the fault lines in Libya. It illustrates how difficult national reconciliation is going to be in some areas. It can also be seen as an example of the victors in the war that overthrew Gaddafi imposing summary and brutal justice on some of the communities that sided with the former regime and were vanquished.

Ghost town

As you enter Tawergha from the main road, the name is erased from the road sign. It is now eerily silent but for the incongruously beautiful bird song. There were a few cats skulking about, and one skeletal, limping dog.

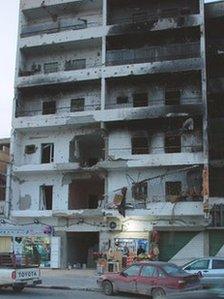

Building after building is burnt and ransacked. The possessions of the people who lived here are scattered about, suggesting desperate flight. In places, the green flags of the former regime still flutter from some of the houses.

Buildings show the scars of heavy bombardment, some are burnt out shells, some are just abandoned. The town is empty of humans, apart from a small number of Misratan militiamen preventing the return of the town's residents.

Those that escaped the town are now scattered across the country. As many as 15,000 people are in Hun, in central Libya. Some are in Sabha and Benghazi, and more than 1,000 are in a refugee camp in Tripoli.

This camp, run by the LibAid humanitarian organisation, was a building site abandoned early in the uprising by the foreign construction workers who lived and worked there. It teems with women and children. There are men about, but they are very few and keep out of sight. The women are ready to talk but they want to cover their faces.

Umm Bubakr can't trace one of her sons. "They bombed and shot at us and we had to run away. I ran away with my kids. I've lost a boy and I don't know whether he is alive or dead. And now we are here, with no future. We are scared, we need a solution to our problem and we want to go home."

She says there are nightly raids by Misrata militiamen on the camp, to take away young men. They are not seen or heard of again.

Umm Saber says militiamen claim her nephew has confessed to raping a woman from Misrata, but she swears that he does not know the meaning of the word.

"There is no evidence that rapes occurred. They drove us out because they want our land and homes," she adds.

The top sign says hospital; the one indicating Tawergha is scrubbed out

Outside in the yard, as we leave the camp, the children gather to sing a protest song about their captivity in the new, free Libya.

People in Misrata explain what happened in Tawergha, the cleansing of a whole town, in terms of the rapes and sexual torture.

They are in no mood for reconciliation or forgiveness. In this conservative society, rape is an unforgivable crime. The victims do not come forward and so there is no way to know the extent of the crimes.

But the authorities in Misrata say that Tawerghans have confessed to rapes and that they have footage taken from mobile phones as evidence.

We were not allowed to see this, but the BBC was allowed to speak to a 40-year-old man who was held by pro-Gaddafi fighters from Tawergha as a suspected rebel fighter. His teeth were knocked out by a rifle butt.

He says that he saw a series of sexual assaults - including more than 20 men suffering torture to their genitals, a man being sodomised with a stick, and Tawerghan women who worked with the Gaddafi military urinating on prisoners who had been forced to lie on the ground.

Riyadh and Osama insist they are innocent and want their day in court

Assuming evidence of rapes and other crimes eventually emerges, it seems that Tawerghans are being collectively blamed for the crimes of a few people.

And because the people of Tawergha were largely supportive of Gaddafi, Misrata's triumphant militias seem to be holding them responsible for the far greater crimes of the former regime in its last months.

In Misrata, workmen are converting the former state security building into a prison, floor by floor. Conditions here appear to be good, though it is overcrowded.

The prison is clean and organised. Medecins Sans Frontiers (MSF), a humanitarian organisation, runs a small hospital, a pharmacy and a counselling service in the prison.

About 60 men from Tawergha are held here. A prison warden invites volunteers to speak to us. He insists they can speak freely and there will be no repercussions.

Torture claims

Riyadh steps forward. He insists he was not involved in rape, though he believes such things did happen. He says no-one has yet investigated his case or charged him with anything. The jail is not a bad place to be, he says, because outside it he would be in great danger. Riyadh hopes he will get his day in court and clear his name.

He urges his uncle to come forward to talk to us. Osama is a lot less voluble, but he shows what he says are scars from a beating with a heavy electrical cable he received from militiamen in Misrata after he was stopped at a checkpoint.

"I am innocent and want to be judged, but it is taking a long time. The people who committed crimes should be punished, not me," Osama says. "I'm obliged to stay a refugee. That's the situation. We will not be able to go home now, these people will not allow it."

This is pretty much Najia Waks' view of the situation. Najia had to move out of her home when it was destroyed by a rocket during the siege of Misrata. She lost four relatives in the war.

We meet her in a school on the outskirts of Misrata where she is taking part in a sewing workshop. Psychologists from MSF are also here, helping women and girls deal with the trauma of the siege they suffered.

Najia has no direct experience of the rapes and torture allegedly carried out by people from Tawergha, but she is in no doubt that they happened.

One of the teachers working at the school tells me that she cannot say herself if the rapes happened or not. "Everybody talks about this, but no-one really talks about it. It is too shaming," she explains.

Some of the women have lost husbands, sons or brothers in the fighting. They are being offered training so that they can support themselves.

Schoolgirls dance to patriotic songs as part of attempts to help them with stress and trauma

Children's drawings on the wall mock Gaddafi and his family. The young girls dance and sing songs celebrating victory, bravery and martyrdom - above all else, martyrdom. Pictures of dead relatives hang around their necks.

There is no question that the people of Misrata suffered terribly in the siege - the damage from bombardment is everywhere.

Mohammad Bashir al-Shanbah, the man who has founded the Martyrs' Museum on one of the main streets in the city, says that more than 1,200 people from Misrata died in the fighting. Hundreds of people are still missing, unaccounted for.

His museum is a kind of gallery. Pictures of all those who have died cover some of the walls. There are pictures of people killed in purges carried out in the city by the Gaddafi regime in the city as far back as the 1980s. In front of the museum, you can wander among piles of the various shells, bullets, heavy guns and grenades that were used against the city. The golden fist that once stood in Gaddafi's compound in Tripoli is here too, a trophy that families come to be photographed beside.

Anyone who died in the cause of overthrowing Gaddafi is a martyr in today's Libya - the discourse of martyrdom is almost suffocating. Every speech opens with prayers for the martyrs, the TV stations are saturated with songs thanking the martyrs for their sacrifice. The central square in Tripoli has been renamed Martyrs' Square. The people of Misrata have adopted this language wholeheartedly.

War-torn city: Misrata suffered three months of intense siege

In the politics of the new Libya, Misrata is striking a hard bargain. Its militiamen continue to hold onto territory and weapons taken in the fighting. Their military successes and their suffering in the war leave them feeling entitled to a share of power.

Officials in Tripoli have said that there will be an investigation if any acts by fighters from Misrata have broken the law. But it does not appear that anyone is being held to account for the events in Tawergha.

With the townspeople being stopped from returning to their homes, it can be argued that the abuse is continuing and being compounded.

A striking aspect of Libya in this immediate post-Gaddafi period is that the regional or provincial centres - Misrata, Benghazi and Zintan for example - are dictating to the political centre, Tripoli, the capital and the seat of government.

Many cities and communities suffered terribly in the war. Tawergha and Gaddafi's home town of Sirte, which was devastated by heavy shelling, are just two examples.

But they have no voice in the new Libya, as they were on the losing side.