A trip down Kafala Alley - and Sarkozy Avenue?

- Published

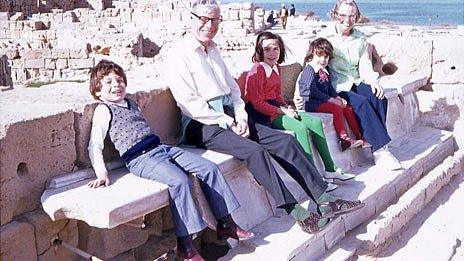

Visiting the Roman ruins at Sabratha with sisters and English grandparents

Forty years of Colonel Gaddafi's rule have been swept away in Libya this year, but when I returned to the country I left at the age of 10, I found some things had barely changed.

"Wishwasha" is one of those perfect Libyan words.

It refers to the people who inform on you to the secret police.

The word is onomatopoeic - if you say it just right, with your hand shielding your mouth, it sounds like malicious whispering.

The word has not always meant informer - for older Libyans, it still means mosquito.

Fear of the wishwasha is gone now.

People come and go, meet and talk, criticise, complain and gossip with glee.

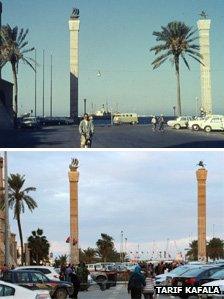

Cars were scarce on Green Square in 1971... and it's now "Martyrs' Square"

By one count, in Tripoli alone, 500 new civil society groups have been set up - political parties, pressure groups, newspapers and magazines, environmental groups, even an animal welfare society.

Everyone who is anyone is convening a conference to address some pressing ill.

All this politics is exciting and chaotic. Two of the conferences I attended ended in tetchy disarray, as debate turned to argument and then boiled over into shouting.

At times, Libyans seem drunk on their new freedoms.

Not everyone is thrilled with the make-up of the new government but many people I spoke to were proud that they have a government, and that the ministers could be seen nightly on TV, answering hostile questions and being hassled into doing something about what matters to them.

'The Mafia'

I anxiously watched the Libyan uprising at a distance, from England.

The protests turned almost immediately into a war, with terrible acts committed on both sides, and eventually the bloody drama of Muammar Gaddafi's end.

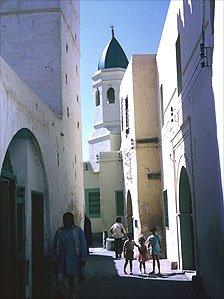

Tarik in Kafala Alley

It took only nine months to undo four decades of rule by a family often referred to now as "the Mafia".

But the fighting opened up existing fault lines in Libya and of course, where some Libyans are triumphant, others have been left vanquished, destitute and scattered.

And there are so many armed men, everywhere you look there are guns.

One of the most startling and immediate effects of the revolution is to sweep away all signs - on the surface at least - of Gaddafi himself.

He was a vain man, and his image and slogans were everywhere, but the only place you see him now is in the gaudy graffiti.

He is often depicted suffering another gruesome death.

Nicolas Sarkozy Avenue

Names are being changed too.

A huge tower in central Tripoli used to be known as Fatah Tower, in honour of the revolution that brought Gaddafi to power. Now it is Tripoli Tower.

Green Square in the centre of the city is now Martyrs' Square.

The Golf Club beach - scene of many childhood holidays

There seems to be a plan to change Algeria Place into Qatar Place. Algeria offered no backing during the uprising, as far as the revolutionaries are concerned, while Qatar was actively supportive.

There is talk of a Nicolas Sarkozy Avenue - France was the first government to recognise the National Transitional Council in Benghazi.

That is another key word for the new Libya, everything is run by a council these days. The old regime was very fond of committees.

Then there are the inevitable ironies of revolutions.

The current government is doing its work from the building that once held the General People's Committee, the body that ostensibly governed the country.

A grouping that is trying to fashion itself into a moderate Islamist party has set up shop in the office of Abdullah Mansour, the former head of Libyan television.

Childhood places

While in Tripoli, I went on pilgrimages to some significant sites from my childhood.

The Golf Club is now gone completely.

Tarik and his sisters visiting the old city back in 1974

It lost the golf course before I was born but retained the name, the clubhouse and a wonderful stretch of beach where most of our summer holidays were spent.

A few years ago, someone in power decided to level the clubhouse and dumped the rubble on the beach, leaving a huge mess that scars the seafront to this day.

However, my school (then the American Oil Company School) was still there, barely changed but a little shabby.

It has the same rows of lockers, the same classrooms separated by little lawns containing the same furniture, the covered walkway, the gym - exactly as they were but for a few coats of paint.

I visited Kafala Alley, a short, narrow street on the edge of Tripoli's ruined old city that once housed my father's extended family.

As a young boy, he lived in a classic Libyan home - three floors with small windowless rooms opening out on to a central courtyard.

And the home where I grew up, in a newer part of Tripoli, is still there - weathered and worn, lived in by some former army general who will not move out.

I peered through the gate into the garden.

The curtains in my old bedroom window were drawn closed.

Now that my wife and family are finally going to get to visit Libya, I am going to teach my children some more essential Arabic.

That annoying thing that buzzes around your ear just as you are about to fall asleep will definitely be a wishwasha.

We're going to reclaim the word.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: A 30-minute programme on Saturdays, 1130.

Second 30-minute programme on Thursdays, 1100 (some weeks only).

Listen online or download the podcast

BBC World Service:

Hear daily 10-minute editions Monday to Friday, repeated through the day, also available to listen online.

Read more or explore the archive, external at the programme website, external.