Is a cure for the common cold on the way?

- Published

In the northern hemisphere, cold and flu season is upon us. But the coughing, wheezing and spluttering masses that hit the streets each winter could, some scientists hope, soon be a thing of the past.

The reason for this optimistic thought is the progress being made towards the creation of a drug known as an antiviral.

Just as antibiotics kill many different types of bacteria, antivirals could kill multiple viruses, from the ubiquitous cold and flu to the life-threatening hepatitis virus and HIV. They could even prove crucial in the case of viral epidemics like Sars and bird flu.

Existing antiviral drugs are tailored to specific diseases - HIV, hepatitis and certain types of flu for example. Vaccinations are also very virus-specific and have to be redeveloped at great cost as a virus evolves.

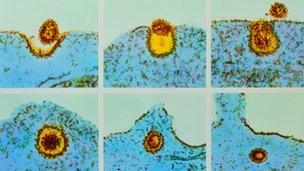

Viruses have special tags on their outer layer that allow them to break through the cell wall

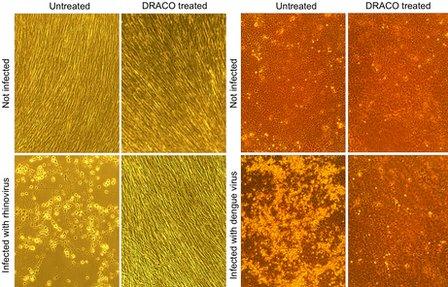

But Todd Rider, a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is developing an antiviral drug called Draco, which has proven successful against all 15 viruses to which it has been applied in lab trials with human tissue and mice.

These include the common cold, H1N1 or swine flu, a polio virus, dengue fever and the notorious and fatal Ebola virus.

To produce it, Mr Rider took an unusual approach, "wiring together" two natural proteins - one that detects virus entry, and another that acts as a suicide switch that kills the infected cell.

"I studied both biology and engineering back in the dark ages and really wanted to combine those studies," he says.

"Everyone in both departments thought I was crazy."

The dream of a broad-based antiviral drug has for years been a holy grail for microbiologists.

Recent developments in biotechnology - especially the ability of computers to analyse reams of information on DNA and the genetic make-up of viruses - has allowed for great leaps in scientific understanding of how these micro-organisms work.

This has brought a few researchers closer to the goal of a broad-based antiviral, targeting the problem in several different ways.

Last year, a breakthrough study at Cambridge University showed that cells have an internal system which fights and kills viruses. It was previously thought that once a virus succeeded in entering a cell, infection was inevitable.

Dr Leo James, the author of this study, is now working on creating antiviral drugs that can latch on to a virus and destroy it inside the cell.

At Mount Sinai Medical School in New York, Professor Peter Palese has developed an antiviral drug that has so far proven very successful against influenza, though less so against other viruses.

And in a laboratory at the other side of the US, Dr Benhur Lee stumbled across a drug that seemed to be effective against several viruses including various pox viruses and Ebola. He soon realised it only worked against viruses that shared a distinct characteristic, a greasy outer membrane or lipid envelope.

Dr James maintains some scepticism about Mr Rider's study.

"It is potentially very exciting but because the results are so unusual and because it was published in an unusual journal it needs to be proven by others," he says.

PLoS One, the online journal which published the paper encourages ideas that challenge established thinking.

Draco appears to have a greater range than its rivals, but it will be several years before Draco can be tested on humans. First the drug will have to go through several rounds of testing on larger mammals.

"Translating from the lab to people is really quite hard," says immunologist Hugh Pennington, Professor Emeritus at Aberdeen University.

Viruses and human cells become closely linked on infection, as a result there are many possible side-effects of a drug like this.

In the 1950s, scientists thought they had come up with a similar broad-spectrum antiviral wonder drug, interferon.

The drug causes an infected cell to secrete a warning signal to other cells, allowing them to build up their natural defences. However, it also triggers the immune system to send white blood cells to the infection, which can cause inflammation of the area, fever, aches and pains.

"Interferons are fantastic drugs," says Wendy Barclay, chair of influenza virology at Imperial College London.

"They are still used today, to treat hepatitis C virus. But if you had a mild virus infection like a common cold you would not want to take interferon to deal with it because it would make you feel horrible, even worse than the cold was making you feel.

"The problem with using that same approach today to develop a broad-spectrum antiviral is always the worry that something in your strategy is going to trigger that same response."

Like interferon, Draco is a protein and has the potential to provoke an immune response. This could be especially problematic when the drug is administered a second time. But no immune response has been observed in mice so far.

For the average human, who suffers through a cold up to four times a year, antivirals could be the answer to days of misery - and businesses could save weeks of lost work hours.

But for those on the front line of healthcare, it could mean much more.

A broad-based antiviral could obliterate the threat of a global pandemic and mitigate health scares such as that caused by the Sars virus in 2002 or bird flu in 2009.

"No-one can say when the next pandemic will occur, it may be next year or it may be in 100 years' time," says Hugh Pennington.

"We're still in the niggling worry scenario even when we are very optimistic… If we had a wonder drug like Draco might be, we could sleep much easier at night."

Find out more about Todd Rider's work and the search for a broad-based antiviral on Discovery from the BBC World Service. Listen to the programme here.