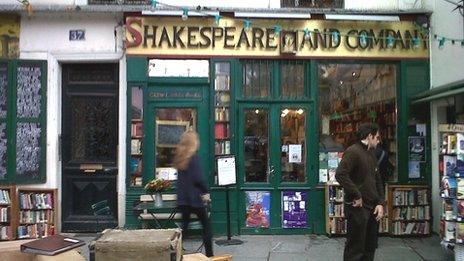

Shakespeare and Co: A writer's haven on the River Seine

- Published

George Whitman, who died this week, ran a remarkable Paris bookshop that has for decades been more than just a place to buy books in English, but also a writer's refuge and tourist destination - a place with an atmosphere all its own.

George Whitman made his money selling books, but he never forgot what he owed to those authors.

His bookshop was a refuge for them. Over the decades, thousands of writers have helped out there, giving their time in exchange for a few hours, or even longer, with kindred spirits.

Whitman's dictum was, "Give what you can, take what you need."

A few lines of WB Yeats are painted on the wall: "Be not inhospitable to strangers, lest they be angels in disguise."

Visiting authors and students were able to work here, sleep amid its piles of books and soak up its unique literary atmosphere.

A few weeks ago, before George Whitman's death, I talked to his daughter Sylvia, about joining those ranks of writer-volunteers. Then, not long after, I stepped into the warm glow of Shakespeare and Company.

"And this is the section to do with Paris," said Linda at the counter, in her Irish lilt, starting my grand tour of the bookshelves.

It is a grey Monday morning, not a time you would expect many people around, but already the shop is buzzing with bibliophiles.

The store was named after another which used to stand not far away, also by the River Seine, a gathering place for the likes of James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. That Shakespeare and Company was owned by a woman called Sylvia Beach.

George Whitman named his own daughter Sylvia after her. Reputed to be the grand-nephew of the American poet, Walt Whitman, he had his own radical friends in Paris.

The work of these 1950s Beat poets occupies not just a section but a whole glass case in the shop.

His daughter took over the reins a few years ago and, as some wondered whether the e-book would come to replace its paper and ink counterpart, she took Shakespeare and Company online to promote its events and history. The virtual book seemed not to matter. As ever, it was all about just being there.

Linda guides me past poetry and the modern fiction sections, and through a series of tiny rooms which have the feel more of a library than a commercial enterprise. Mr Whitman described them as being like the chapters of a novel.

I study walls papered with news cuttings and postcards, and walk up the stairs - through "plays and playwrights" - to the hallowed upper floor. This is where Sylvia Beach's own library sits, in a room now used for events.

Amid the hush, I hear a familiar "tack, tack, tack, thunk" and a glimpse into a cosy writer's cave reveals someone sitting at an old portable typewriter at a desk, and shelves laden with well-thumbed books about how to get published.

The only other sound, apart from the typing and the conversation, comes from a piano on which customers sometimes get carried away. "It's nice," says Linda, "the sound carries downstairs to the tills."

She then gives me the science fiction and fantasy section to sort.

Putting the books into some kind of order is a strangely comforting task. Conversations continue around me.

A woman is flouting the "Please no photography" notice, directing a mobile phone photo shoot in the history section. "No," she instructs, "I want that shelf to be in it."

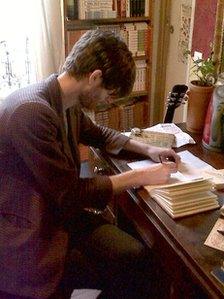

Poet Jimmy Hargreaves finds living at the bookshop helps him write

Someone else is seeking advice on a good title for a book club reading, which results in a lively dialogue about international authors.

I become fascinated by the role of the bookshop assistant.

In my hands, sundry titles are unearthed from darker corners of the shop, and putting them into the few gaps I find in the shelves means I am bringing them, and their authors, into the light.

On the stairs another volunteer is gamely trying to organise her section, precariously lunging with piles of books, between people going up and down.

We smile as a light bulb blows in the crime section, leaving it in mysterious darkness.

The light restored, a so-called "mirror of love" is revealed upstairs, its surface covered with notes and billets-doux, love poems and declarations.

Here you can see not only a fascination with books, words and with Paris, but also the reflections of book lovers chatting over dusty tomes. "Oh, that's my favourite Auster too," says one.

My session as a volunteer over, I go to collect my bag from a locker in the labyrinth upstairs. It turns out to be the lair of a writer-in-residence, 25-year-old Jimmy Hargreaves.

He is a published poet from Grimsby and, with his long hair flopping over his chiselled face, he looks every inch the part, head bent over his paper notebook.

"I'm a dreamer," he tells me. "This is a place where I can create."

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: A 30-minute programme on Saturdays, 1130.

Second 30-minute programme on Thursdays, 1100 (some weeks only).

Listen online or download the podcast

BBC World Service:

Hear daily 10-minute editions Monday to Friday, repeated through the day, also available to listen online.

Read more or explore the archive, external at the programme website, external.