Northern Lights: Chasing the aurora borealis

- Published

In America "storm-chasers" are the intrepid types who pursue tornadoes, and sometimes hurricanes. But the Arctic Circle has its aurora chasers - people who speed around in search of the best views of the aurora borealis, or Northern Lights.

"Last week we saw one that had everything - spiralling, curtains, ribbons, greens and reds, and the whole sky lit up. We were amazed at what was unfolding before us," says Andy Keen.

Five years ago he left his job running a charity in the UK to move to Ivalo, a remote village in northern Lapland, Finland, latitude 68 degrees - two degrees above the Arctic Circle.

"I saw a TV documentary about the Northern Lights. So I went there to have a look. Now I'm absolutely addicted," he says.

Mr Keen's company, Aurorahunters, now takes seven tourists a week on hunting trips in the Arctic wilderness to search for the Northern Lights.

"The reason I chose here is because the population is very low, there's very little light or noise pollution, and it's perfect hunting territory for the aurora," he says. (See a slideshow here, external).

The aurora borealis is named after two gods, one Roman, the other Greek

There are similar companies operating elsewhere in Finland and in neighbouring Norway where the official tourism website describes the aurora as "a tricky lady". It adds: "You never know when she bothers to turn up. This diva keeps you waiting."

But aurora chasers like Mr Keen are impatient - they go after the diva instead of waiting for her to come to them.

That means studying charts to find clear skies. "We look at all the weather data," he says. "We're checking the cloudiness reports. Looking at the cloud movement, the density of the clouds. We're pinpointing a place we feel at that particular time there will be a hole in the cloud."

When a location has been selected, Mr Keen and his group jump into minibuses and head into the wilderness, sometimes taking to sledges pulled by huskies to reach the most remote areas. They often see moose and bear tracks and have ventured as far north as the Arctic Ocean.

All to get the best vantage point to see the aurora borealis, named after the Roman goddess of dawn (Aurora) and the Greek name for the north wind (Boreas).

However, it's the solar wind, not the north wind, that is the determining factor.

Sunspots

"The process that causes the auroras is similar to the physics of a neon sign," says Joseph M Kunches, Space Scientist at America's Space Weather Prediction Center, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA).

"That is, an electron interacts with neutral atoms and causes light of various colours to be emitted. What happens when the aurora brightens is particles that start at the sun - and most of these are electrons - are brought by solar winds towards the Earth and guided by the Earth's magnetic poles.

"When the particles interact with the Earth's atmosphere, they excite molecules already there, and they emit light.

"The colour of that light is dependent upon which gases in the Earth's atmosphere - oxygen, nitrogen, or some other - are being excited. And when the solar winds are stronger and more 'gusty', the auroras will be more brilliant."

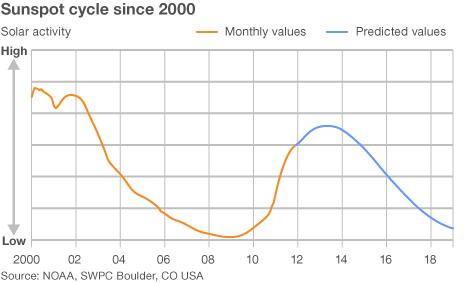

The strength of the solar wind increases or decreases in line with the number of sunspots, and it goes in cycles.

Aurora hunters are in for a treat in the coming few years, according to Mr Kunches. "Solar activity tends to increase rapidly every 11 years or so. According to our predictions, we are about to enter in 2012 and 2013 a new wave of heightened activity. That translates to more frequent auroras," he says.

The South Pole is affected by solar activity in the same way. The difference is seasonal. In the northern hemisphere, because it is winter now and often dark, we know of the auroras because we can see them.

"Those same dynamics are going on in the southern hemisphere too, but towards the South Pole the latitudes are bathed in 24-hour daylight and that means you just can't see it," Mr Kunches says.

In the north, the aurora can be seen from Scandinavia, Russia, North America and northern Scotland.

Crown of light

In Finland, photographer Martti Rikkonen is polishing his camera lenses at his home in Inari, in northern Lapland. He says today is a nice mild day in Inari. It's only -5C, and there's just 25cm (10ins) of snow. "It could be very much colder," he says.

Mr Rikkonen says Finns often take the Northern Lights for granted. "For many people it's nothing special, because we have them so often. You can see them here in clear weather perhaps for 200 nights of the year. But when they are good, everyone is interested because there is so much colour and they are fantastic."

He has vivid memories of one night. "I knew something special was happening because there was so much light around. I stepped outside and saw a corona, or crown of light, high in the sky, coming from all directions. There were actually two coronas. Green and red. I have only once seen two coronas, and it was really something special."

Mr Rikkonen says he tried to take photographs of what he was seeing that day, but was disappointed with the results. "It just could not be captured in a photo. It covered the sky. I was disappointed when I saw the photos later."

But Mr Rikkonen has taken many photos of the aurora that have not disappointed. He has judged Finland's top nature photography competition, which is held in Helsinki each year. He won it himself in 1995 with a photo, of course, of the aurora.

Clear skies

Like Joseph Kunches at the NOAA, Andy Keen also sees bright prospects for the Northern Lights in 2012.

"In the early months of the year, particularly January, February, mid-March, we get some really nice clear skies," he says.

By then most of the heaviest snows have fallen, so there is snow on the ground, but fewer snow clouds in the sky.

The summer, when the nights are short or non-existent, is downtime for the aurora chasers. The longer nights begin to return in the autumn, and the snow usually in October, though it was later this year.

There is something dream-like about these unpredictable light shows, and some people cherish an ambition to see them for years.

Christmas and New Year are popular times for realising the dream, Mr Keen says, with the polar nights, the auroras, and the festive season combining in one "romantic experience".

Listen to more on this story, and see a slideshow of the aurora borealis at PRI's The World, external, a co-production of the BBC World Service, Public Radio International, and WGBH in Boston.