Jamaica's patois Bible: The word of God in creole

- Published

The Rev Courtney Stewart reads extracts of the "Jiizas buk"

The Bible is, for the first time, being translated into Jamaican patois. It's a move welcomed by those Jamaicans who want their mother tongue enshrined as the national language - but opposed by others, who think learning and speaking English should be the priority.

In the Spanish Town Tabernacle near the capital, Kingston, the congregation is hearing the word of God in the language of the street.

At the front of the concrete-block church, a young man and woman read alternate lines from the Bible.

This is the Gospel of St Luke in Jamaican patois - or more precisely, "Jiizas - di buk we Luuk rait bout im".

The sound of the creole, developed from English by West African slaves in Jamaica's sugar plantations 400 years ago, has an electrifying effect on those listening.

Several women rise to testify, in patois, to what it means to hear the Bible in their mother tongue.

"It's almost as if you are seeing it," says a woman, referring to the moment when Jesus is tempted by the Devil.

"In the blink of an eye, you get the whole notion. It's as though you are watching a movie… it brings excitement to the word of God."

The Rev Courtney Stewart, General Secretary of the West Indies Bible Society, who has managed the translation project, insists the new Bible demonstrates the power of patois, and cites a line from Luke as an example.

'Vulgar' words

It's the moment when the Angel Gabriel goes to Mary to tell her she is going to give birth to Jesus.

English versions read along these lines: "And having come in, the angel said to her, 'Rejoice, highly favoured one, the Lord is with you: blessed are you among women.'"

"Now compare that with our translation of the Bible," says Mr Stewart.

"De angel go to Mary and say to 'er, me have news we going to make you well 'appy. God really, really, bless you and him a walk with you all de time."

Mr Stewart says the project is largely designed to bring scripture alive, but it also has another important function - to rescue patois from its second-class status in Jamaica and to enshrine it as a national language.

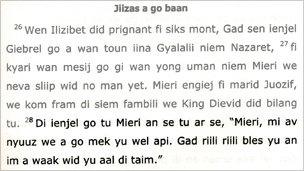

Jesus will be born... Luke, chapter one, verses 26-28

"The language is what defines us as Jamaicans," insists Courtney Stewart. It is who we are - patois-speakers."

The patois Bible represents a bold new attempt to standardise the language, with the historically oral tongue written down in a new phonetic form.

For example the passage relating the angel's visit to Mary reads: "Di ienjel go tu Mieri an se tu ar se, 'Mieri, mi av nyuuz we a go mek yu wel api. Gad riili riili bles yu an im a waak wid yu all di taim."

The New Testament has been completed by a team of translators at the Bible Society in Kingston - working from the original Greek - who intend to publish it in time for the 50th anniversary of Jamaica's independence from Britain on 6 August next year.

Most children arrive at school speaking creole, and need to learn English from scratch

But some traditionalist Christians say the patois Bible dilutes the word of God, and insist that creole is no substitute for English.

Bishop Alvin Bailey, at the Portmore Holiness Church of God near Kingston, argues that Patois is too limited a language to represent the nuances of Biblical text, and has to resort to coarse expressions to makes its meaning clear.

"I don't think the Patois words can effectively communicate what the English words have communicated," he says.

"Even those (Patois) words that we would want to use to fully explain what was in the original, are words that are vulgar."

Many others see the elevation of patois as a backward step for Jamaica, in a globalised world demanding English.

The vast majority of children arrive at school speaking little apart from the creole of their ancestors, and teachers are under intense pressure from the government to replace it with English.

The head teacher at St Richard's Primary School in Kingston, Jacqueline Williams, says she can understand the policy, because people make up so much of what Jamaica exports.

"If they do go elsewhere they would have to have English as the language of communication," she says. "That's why it is being sold as our first language."

That pressure is felt by even by the smallest of the children in their smart uniforms playing outside the two blocks of brightly-coloured classrooms.

"A little child in our class who can only speak that way... is going to be embarrassed," says Mrs Williams.

"I think that esteem problems can develop because of it."

Two girls from St. Richard's Primary School in Kingston Jamaica, perform the Patois poem Cuss Cuss by Jamaican poet and activist Louise Bennett

Stigma

Linguists at the University of the West Indies in Kingston, who have been working on the translation, insist that patois is an authentic language, with its own tenses and consistent grammatical rules.

Dr Nicole Scott claims that the response to declining exam results in English - which has been to reinforce the emphasis on English - is counter-productive.

"Literacy in patois would help the students to appreciate the structures that are used in English," she says.

Dr Scott says the new system of writing used the in patois Bible is critical if language skills are to be taught in creole, and that the Bible holds sufficient sway in Jamaica to act as powerful model.

"I think it will be massively, massively, helpful. People will realise they can hear the word of God in their own language and understand it very well, this same language that has been stigmatised for so long."

Patois was developed from English by African slaves on sugar plantations

Faith Linton, a linguist of almost 80 who was one of the founders of the Patois Bible project, believes the way patois continues to be looked down upon threatens the very future of Jamaica itself.

From the balcony of her old plantation estate house on the north coast of Jamaica, managers once kept an eye on slaves working the sugar cane.

She spoke nothing but patois until she was 12.

"The damage is deeply psychological," she insists. "The patois-speaker feels inferior, full stop.

"Because the model is the white English man, his language and educational standards… and we have not been able to attain it.

"Out of this sense of inferiority will come violence, illiteracy, disturbed behaviour and damaged emotional attitudes. All those spring from the idea that my identity is inferior."