The beginning of the end for the mademoiselle?

- Published

- comments

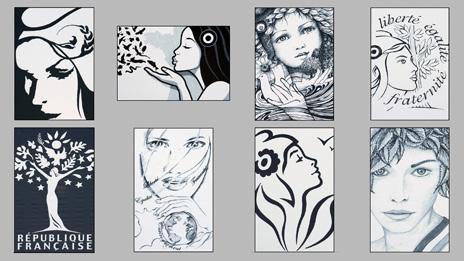

The symbol of French liberty - and "egalite" - is a young woman, Marianne

A town in Western France has banned the word "mademoiselle" - the French equivalent of "miss". The move comes as feminist groups campaign for the word to be consigned to the dustbin of history everywhere. Could its days be numbered?

There are no longer any "mademoiselles" in the town of Cesson-Sevigne.

The small Brittany community has banned the use of the term in all its official documents, arguing that women, like men, should not be defined by their marital status.

From now on, teenagers, greying grand-meres and 30-something career girls there will all be known as "madame", just as men of all ages become "monsieur" as soon as they grow out of shorts.

The Germans waved goodbye to their "Fraulein", as a term to addres adult women, in 1972. In the English-speaking world the use of "Miss" is in decline - and on occasions when an honorific is required, "Ms" provides a convenient way of avoiding being pigeon-holed as either "Miss" or "Mrs".

But in France - just as in Spain with their "senorita" and Italy with their "signorina" - things are a bit different. "Madame" or "mademoiselle" can even be used to address someone in the absence of a name - "Would Madame care to be shown round the church?" a verger asks Flaubert's Madame Bovary.

It's a superfluous box, say feminist campaigners

These forms of address are not just about formality and respect, but also about flirtation and familiarity.

Doyennes of the stage and screen retain their "mademoiselle" status, regardless of how long in the tooth they are. Waiters can gently flatter a lady of a certain age by calling her "mademoiselle", and officials can patronise by refusing to call a woman "madame".

But for the mayor of Cesson-Sevigne, Michel Bihan, the key thing is eliminating "discrimination".

Elected in 2008 on a sexual equality platform, he and a group of like-minded councillors have been transforming the town of 16,000 to change anything deemed unequal.

The changes have been both practical and symbolic - there are now changing rooms for women at the town's stadium and council texts use both masculine and feminine wording when women might be among the number referred to.

His slogan at the last election was "une ville pour tous" ("a town for all") though he now says it should have been "une ville pour tous et toutes", using the feminine form of the word for "all" too.

"It just seemed like the natural step for us. It is symbolic - a signal, a gesture, but one among many," he said of the decision to ditch "mademoiselle".

It's not the first time a French municipality has taken such a step. The city of Rennes, close to Cesson-Sevigne but far larger, officially dropped the word in 2007. But this time there is also a national campaign by feminist groups against "mademoiselle", external.

They want Madame to be de-coupled from the idea of a married woman or wife to become, like Monsieur, a general term of address.

Women can buy badges with the "mademoiselle" option crossed out and are encouraged to download a letter to their electricity provider or bank informing them why wish to be called "madame".

But why, others have argued, should we fret over the linguistic cosmetics of which box on a form gets ticked when key issues such as equal pay, availability of child-care and political representation remain bigger practical obstacles to a fully equal society?

Professor of applied linguistics Dr Penelope Gardner-Chloros, of Birkbeck University, says that a society's language - and how it chooses its terms of address - can reflect deeply ingrained attitudes.

"[Language] it is a sensitive indicator of the distinctions that a society makes - so if it is important to know if a woman is married or not, then it will be indicated in language," she explains.

"'Mademoiselle' was a courteous title and there was even a male equivalent - 'Mondamoiseau', though it was very rarely used," and later fell out of use completely. (The word "damoiseau" can be translated as "squire".)

More equal societies tend to put less emphasis on regulating forms of address, Prof Gardner-Chloros says.

The fact that the words "Miss" and "Mrs" are used less frequently in English than in French suggests that British society has had less use for the distinction. In a similar way, English dropped the word "thou", a more familiar version of the pronoun "you", as time went by, while French has retained "vous" and "tu".

Language, she says, can sometimes drag its feet behind social norms. The adjustment with "Fraulein" came in Germany in the 1970s, and it may be that the same is beginning now in France.