A Point of View: The shady side of gardening

- Published

Gardens such as those at Hampton Court might have a darker side

Say it with flowers, goes the saying. But sometimes the message is not so innocent - that beautiful garden may have more to do with spin and intrigue, says historian Lisa Jardine.

Sir Francis Bacon, Lord Chancellor to King James I of England, and Father of Modern Science, was a lifelong enthusiastic gardener. The opening lines of his essay, Of Gardens, first published in 1625, will be familiar to many listeners:

"God Almighty first planted a Garden; and, indeed, it is the purest of human pleasures; it is the greatest refreshment to the spirits of man."

These lines came back to me when I read in the Radio Times this month that the celebrity gardener Alan Titchmarsh had expressed the view that gardening is more comforting and stable than politics.

"It has a consistent point of view. And that is that a piece of ground should be cherished… The natural world has a kind of stability. There is a cycle that's reliable and sound, and that is real life to me... Gardening is the stuff of life."

On the face of it, Bacon and Titchmarsh seem to share an idealised view of gardens as a place where innocence can still be nurtured in a nasty world.

But the reason Bacon sprang immediately to mind was because the 17th Century Lord Chancellor was acutely aware of the way that expertise in horticulture, garden design, plantings and prunings could be used to worldly effect. Throughout his life he deployed his gardening skills to gain favour with those in power.

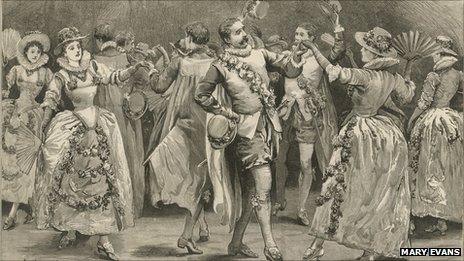

On Twelfth Night 1613, when he had already acquired a considerable reputation for planning extravagant groves, walks, fountains and flower gardens at his country house at Twickenham and his family seat at Gorhambury, Bacon personally designed and paid for a spectacular Masque of Flowers to be performed in the outdoor Banqueting House in the grounds of Whitehall Palace, by the gentlemen of Gray's Inn.

The Masque of Flowers in action at Gray's Inn in 1613

The masque's performance was the culmination of the celebrations for the wedding of James I's favourite Robert Carr, Earl of Somerset, to Frances Howard. Its setting was an elaborate artificial garden, perfectly contrived to mimic the real thing, and Bacon spent a small fortune on it, as reported by a contemporary:

"Sir Francis Bacon prepares a masque to honour this marriage, which will cost him in excess of £2,000, and though he has been offered some help by Gray's Inn… yet he would not accept it, but offers them the whole charge with the honour: marry his obligations are such to his Majesty as to the great Lord [Somerset], and to the whole house of Howards as he can admit no partners."

Bacon was a green-fingered soul

A printed description of the Masque of Flowers survives, from which we can appreciate the gorgeous simulated beauty of its garden setting:

"Every quarter of the garden was finely hedged about with a low hedge of cypress and juniper [we learn], the knot-gardens within set with artificial green herbs… In every corner of each quarter were great pots of gilly-flowers… The two farther quarters were beautified with tulips of diverse colours."

The one-night-only performance was a glorious success, attracting enthusiastic praise beyond that for any other wedding-related extravagances. And having ostentatiously honoured the factions of both bride and groom, Bacon's gift succeeded in significantly advancing his political career.

The wedding in question was, however, widely seen as scandalous. The bride Frances Howard's first marriage to the Earl of Essex (when she was only 13) had been annulled on grounds of non-consummation in order that she could marry Carr, rising star at court with whom James I was besotted, and with whom Frances was already romantically involved.

Proceedings included a dubious virginity test (Frances's face was veiled to protect her modesty and there were rumours another girl had been substituted). Her first husband claimed his sexual prowess was impaired by her mocking of his manhood.

Thomas Overbury, a senior member of her household, maintained throughout that the annulment was a sham, and strongly opposed the second marriage. The king had him imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he died mysteriously 10 days before the wedding.

This was tabloid-type scandal, widely reported, and damaging the reputations of all concerned.

Three years later, as speculation and tittle-tattle continued to circulate, and the Somersets fell from royal favour, they were charged with the murder of Thomas Overbury.

At their trial in May 1616, Bacon - creator of that delightful wedding garden and now attorney general - led the prosecution and secured the conviction of both parties. Frances pleaded guilty and was pardoned. Her husband was condemned to death, although the sentence was never carried out and he was eventually quietly freed.

Trodden underfoot

So by the time Bacon published Of Gardens in 1625, a year before he died, and five years after his own political disgrace on charges of accepting bribes, he had a good deal of experience of the way in which an individual's gardening-related activities - however far they seemed from more worldly events - could get enmeshed with their political fortunes.

And indeed, Bacon's writings on the delights of gardens themselves hint at a darker side to its supposedly innocent pleasures.

In Of Gardens, Bacon especially recommends filling the perfect garden with sweet-smelling flowers to perfume the air. And he advises planting paths and walkways with carpets of scented herbs whose fragrance will be released as they are walked on:

"Those which perfume the air most delightfully, not passed by as the rest, but being trodden upon and crushed, are three: that is, Burnet, Wild Thyme, and Water-Mints. Therefore you are to set whole alleys of them, to have the pleasure when you walk or tread."

But in a collection of witty sayings that Bacon also published in 1625, these fragrant walkways provide a more sinister thought about bruising plants underfoot. Good men reveal their sweetness most vividly when sorely tested. Or as Bacon puts it:

"Virtuous men [are] like some herbs and spices, that give not out their sweet smell, till they be broken or crushed."

Bacon says he learned this maxim from his "intimate and dearly beloved friend" Jeremy Betterton, a fellow member of Gray's Inn. It was Bacon and Betterton together who collaborated on another of Bacon's cherished garden projects - the creation of the Gray's Inn walks, which survive to this day as a precious green retreat at the heart of legal London.

Knot gardens were popular in his day

Work began in 1597 on what would become the "lower walks", and the contemporary account books record payments towards "levelling the walks", building stairs for access to the "upper walks", as well as rails and seats. The ambitious plantings included eglantines, pinks, violets, and primroses and large numbers of trees - 132 in 1598 and 58 more in 1601 - particularly birch, cherry and elm.

In 1609, after the death of Betterton, Bacon designed and paid for the construction of an artificial hill or "mount" on the Jockey's Field side of the walks, on which he built a summer house "topped by a griffon", with a loving inscription to Betterton's memory. The mount and memorial were demolished in the 18th Century and shortly afterwards, in 1825, the row of barristers' chambers called Raymond Buildings was built on the site.

According to garden historians, 5 Raymond Buildings - home to a set of entertainment and media barristers that specialise in high profile libel and privacy cases - now marks the spot where Bacon's summer house once stood.

These barristers have represented numerous celebrities against tabloid newspapers and each other:

Formula One boss Max Mosley v News Group Newspapers

footballer Rio Ferdinand v the Sunday Mirror

pop star Peter Andre v glamour model Katie Price

I can't help feeling Bacon would have rather liked the conceit that his memorial mount's location today is marked by the chambers of a set of barristers which, had it been in existence in the 17th Century, might well have represented the Earl of Somerset and his wife.

Their conviction for murder remains a matter for doubt to the present day and was largely based on rumour, gossip and hearsay and clearly politically motivated.

Perhaps had they done so, Somerset might have brought a libel claim against his accusers, or even brought a successful claim against the 16th Century news sheets that the public hue and cry and accusations were an invasion of the Somersets' privacy, not in the public interest.

At any rate, perhaps the innocence and sustaining consolation of gardens is not quite such a simple matter after all. The shadow of political self-interest falls across the sweet-smelling flowerbeds and shady bowers too.

We might recall that other memorable garden quotation - "Et in Arcadia ego" [I too am in Arcadia] - vividly represented in Nicolas Poussin's painting, which takes the phrase as its title. It shows a group of classically-dressed shepherds inspecting this inscription on a monumental tomb in a sunlit garden. Death, or at least, mortality, in other words, also inhabits the garden.