Nasa city that reached for stars now reaches for resumes

- Published

Nasa hopes to build a "mega rocket", the next giant leap in the US space programme, in Huntsville, Alabama

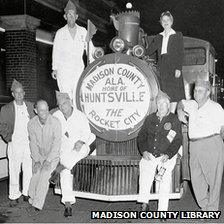

In Huntsville, Alabama, scientists developed the spacecraft that took man to the Moon. It's also where Nasa hopes to build a "mega rocket" - the next giant leap for the US space programme.

But hundreds of scientists and engineers have lost their jobs, and the place dubbed Rocket City is in search of an economic boost.

Karen Murphy has been working for Nasa in Huntsville since college.

In her first job in 1992, her team from the University of Alabama performed microbiology experiments on the space shuttle. They flew bone cells and cancer cells into space to see how they reacted to microgravity.

She's taken part in 20 missions since, studying radiation-shielding and working as an engineer in the Aries programme.

Karen Murphy has spent her entire working life in Huntsville

At the end of September, she was laid off.

"Space flight is a luxury," Ms Murphy says. "It's what you do when your economy and country is good and solid to the point where you can think of things besides here."

The state of the US economy, of course, is far from solid.

The effects of the downturn have hit this usually recession-proof city, which has one of the country's highest concentrations of scientists and engineers.

In the past decade unemployment here ranged between 3% and 4%. Today that figure is 7.7%.

From farms to rockets

At a time when politicians and the public are worried about government spending, the decision to permanently shut down the space shuttle mission last year seemed - for some - an appropriate metaphor for the grounding of American ambition.

Yet Rocket City Mayor Tommy Battle remains stubbornly optimistic.

"The future of Huntsville is bright," Mr Battle insists. After all, he says, the city has gone through radical changes more than once in its history.

Rocket City flourished during the Apollo and space shuttle programmes

Huntsville was a traditional farming community until World War II.

Then a group of German scientists who had surrendered to American forces and were working for the Allies moved in.

They chose to settle near Monte Sano, an Alabama mountain vaguely resembling a Bavarian landscape.

They went on to design rockets for the US, using technology they created during the Nazi regime.

The city has been a major base for Nasa rocket production ever since. It was here, in the 1960s, that the Apollo rockets were built.

And now, after a political stand-off over the future of the US space programme, Huntsville will once again play a crucial part.

In September, the agency finally announced the go-ahead for the Space Launch System, a new "mega-rocket" that will transport astronauts much farther into the Solar System.

It will be built in Huntsville with an initial budget of $1.8bn (£1.2bn).

Lack of vision?

The exact destination and deadline for the new rocket have yet to be finalised. The previous goal of getting back to the Moon by 2020 was cancelled with the end of the Constellation programme.

That decision led to job losses in Huntsville, forcing engineers and scientists to look beyond government-funded projects for work.

Herbert Guendel, one of those recently laid off, is now trying to launch his own small commercial company, Space Operations Inc, to build a capsule to take payloads and people into low orbit and to perform robotic operations.

"Scientists and engineers who have been laid off have now two options," Karen Murphy says. "Either try to go into the private sector or go and work for Redstone Arsenal, which is an army base."

Redstone Arsenal is the number one employer in the city. The Pentagon, of course, is also facing major spending cuts, but that doesn't seem to worry Mayor Battle.

He says the defence business here is booming.

"We are doing foreign military sales in the missile defence and aviation defence field," Mr Battle says. "And we have a lot of equipment coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan that has to be reset."

There is always likely to be work for the talented scientists and engineers who call Huntsville home.

But Richard Brown, who designed one of the engines for the Apollo missions, and spent all his life working for Nasa, laments the lack of vision when it comes to research and exploration.

At the time of the Apollo mission, he says, "nobody wanted a failure. But there was much more freedom to take risks. Today they seem much more hesitant to take risks."