Protests: When's it time to go home?

- Published

- comments

London's Parliament Square has been cleared of protesters after a decade-long battle, activists also face eviction from a camp by St Paul's Cathedral and in the US, Occupy protests have been cleared. Is there a time protesters should pack up and go home?

The aim of a protest is usually to change something. Or keep it the same. To pass a law. Or overturn one. To draw attention to a cause. Or show how much support that cause has.

Protests can be symbolic, but more often than not they aim to disrupt - to picket, to blockade, even just to embarrass.

The protesters want to keep on getting their message across until their goals are achieved. The authorities often want them to stop as soon as they've had their initial say.

So in a democracy there is always a tension between affirmation of the right to protest and the desire for normal life to continue.

Prime Minister David Cameron said in October of the St Paul's protest: "I don't quite see how the freedom to demonstrate has to include the freedom to pitch a tent almost anywhere you want to in London."

The protest at Greenham Common lasted 19 years

New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg criticised the Occupy protest in the city's Zuccotti Park for "making it unavailable to anyone else". He said: "New York City is the city where you can come and express yourself. What was happening in Zuccotti Park was not that."

On Monday, anti-war protesters at the Democracy Village camp in Parliament Square were removed by police seven years after a law was passed which enabled the clearance. On Wednesday, the City of London Corporation won the right to evict Occupy London protesters outside St Paul's Cathedral.

And in the US, Occupy Wall Street protesters were removed by police from a range of sites at the tail end of last year.

The Occupy movement says it is fighting corporate greed, and the protesters at St Paul's have argued their aim is not disruption, insisting that worship can continue easily and that the highway is not blocked.

But what is clear is there is a long line of activists who have wanted to stay until their point was made. Many Protesters in Egypt's Tahrir Square stayed until Hosni Mubarak was deposed on 11 February, but others held on for all their goals to be met.

"I believe there are moments when the desired outcomes of a protest are achieved, a point has been made and going home is the only option," says activist Shahinaz Nabeeh.

The fuel blockade ended after a week in 2000

"But after spending two weeks in Tahrir Square in Cairo during the July sit-in, when many felt the spirit of the original protests was returning, I realised that leaving the square on 12 February shouldn't have been an option until the full demands of the revolution were met."

In Tiananmen Square in 1989, protesters had been there several weeks before the troops moved in and massacred them.

And in democracies, staying power can also be a big part of swaying the undecided.

In the early 1990s, lengthy campaigns tried to disrupt work on new roads in the English countryside. The Earth First! group organised camps and "tree sits" in places like Twyford Down to prevent the M3 extension, outside Newbury to stop a bypass, and Fairmile in Devon, where Swampy became an unlikely celebrity in the battle to stop the widening of the A30.

All of these attempts failed to stop the new roads. But by the late 1990s, after years of protests, government policy had moved away from new motorway building. How much of that was down to the protesters, and how much because of research suggesting that new roads simply created more traffic, is hard to say.

Of course, for many people, hindering lawful action like an approved development is not a legitimate form of protest. Tolerance can have a shelf life.

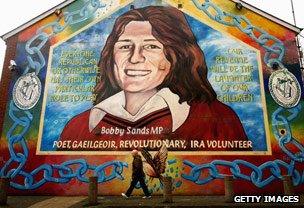

Bobby Sands' protest ended in his death

The fuel protesters who blockaded British oil refineries in 2000 initially enjoyed overwhelming popular support. But after a week, essential services were being disrupted and the inconvenience of not having petrol began to elicit a different response.

The public mood shifted and within days the blockades had ended. The protesters had made their point, but it was time to pack up and go home.

The women of Greenham Common who camped outside the US Air Force base in Berkshire to protest against the deployment of cruise missiles carried on a vigil for 19 years, continuing even after the missiles left the base.

Again, the IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands is remembered because his protest was carried through, resulting in his death.

Dr John Price, a historian of public protest at London's Goldsmiths University, argues there are four key elements that help determine when the job of protesters is done. "For a movement to be successful, worthiness, unity, numbers and commitment need to be demonstrated and maintained."

Indeed shorter protests are just as effective as longer-term occupations but in a different way, according to Price. "A very large, slow-moving march is about showing numbers and unity and is influential in communicating ideas to a large number of people."

Shorter protests can quickly grab attention and put a cause in the spotlight, as with the current US Tea Party movement, which aims to reduce taxes and make government smaller, and intends to echo a long tradition.

Shahinaz Nabeeh in Cairo's Tahrir Square

"In America's history of tea parties, they have always been perceived as fun and quick 'events' that are an effective platform for getting attention," says Joseph Cummins, author of Ten Tea Parties: Patriotic Protests That History Forgot.

Joan Smith, a columnist and human rights campaigner, thinks protesters can undermine their cause by staying too long.

"The St Paul's protesters have ended up getting into an irrelevant argument with the Church of England, which is a diversion from their original critique of the Stock Exchange.

"Once you've met your aims, it's crucial to take your cause forward and I'm not sure continuing to stay outside St Paul's Cathedral takes these protesters' political objectives any further."

In many cases, of course, the issue will be decided by the authorities moving in with an eviction notice.

So the "how long" question that the protesters must answer might be how long before the police move in, or "how long" before public sympathy wanes.