The rise of genocide memorials

- Published

Members of England's European Championship squad have visited the former Auschwitz-Birkenau Nazi death camps. This comes as memorials and museums marking the sites of mass killings around the world witnessed an increase in visitors.

A delegation led by Wayne Rooney and England manager Roy Hodgson took time out from training on Friday to visit the notorious death camp Nazi Germany operated on Polish soil after invading its neighbour during World War II.

Another group headed by captain Steven Gerrard travelled to Oskar Schindler's factory in Krakow.

The visits received a mixed reaction from commentators, with the <link> <caption>Daily Mirror's Oliver Holt saying the "harrowing visit... made an extremely powerful statement"</caption> <url href="http://www.mirror.co.uk/sport/football/news/england-footballers-visit-auschwitz-oliver-869360" platform="highweb"/> </link> at a time "football is wrestling with new and grave concerns over racism among players and supporters".

But for the <link> <caption>Daily Mail's Melanie Phillips, it was a "deeply distasteful football PR stunt"</caption> <url href="http://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-2157369/Euro-2012-The-unique-evil-Auschwitz-deeply-distasteful-football-PR-stunt.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> , which was "intended to cleanse the besmirched reputation of English football".

Yet England's players are not the first footballers to visit Auschwitz. Holland and Italy, who are also camped in Krakow, have already been, as have representatives of the German team.

And they join the millions of tourists who have walked through the iron gates at Auschwitz bearing the legend Arbeit Macht Frei (work makes you free) to pay their respects.

Last year, a record 1.4 million people visited the site, while Holocaust memorials all over the world are also seeing numbers soar.

Dark Tourism

At the same time, other sites of massacres or genocide and cemeteries are becoming increasingly popular with tourists.

Bosnia, Cambodia and Rwanda, are among the destinations on what has become known as the "genocide tourism" map.

Ben and Nicole Lusher made it their mission to visit memorials when they took an unusual five-month trip around the world, starting at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, Israel's official Holocaust memorial.

Ben says that while the couple learnt a lot on their travels, it was Rwanda's main genocide memorial, overlooking Kigali, that stood out.

"It was a new experience for us to be in a place where the genocide was still fresh and almost everyone we saw around the country had been affected," he says.

The couple were both only 10 years old in 1994 when between 800,000 and one million Tutsis and moderate Hutus were killed, so they were also learning about it for the first time.

More typical visitors to Kigali's memorial are tourists who have travelled to Rwanda to see the wildlife and the mountains. Aegis Trust attendance figures state that more than 40,000 foreigners visited Kigali's memorial in 2011.

Canadian Laura Maclean, who went to Rwanda to go trekking, says she made the decision to visit the memorial during her holiday because she thought "it showed respect".

Tour guide George Mavroudis, who charters planes to fly Americans around Rwanda to see the gorillas, says most of his clients ask to visit the memorial.

According to Mavroudis, who has been to the Kigali memorial more than 20 times, tourists believe it is important to understand the country they are in.

The memorial is not the only tourist spot that marks this dark chapter in Rwanda's history.

The Hollywood film Hotel Rwanda is based on the story of the general manager of the five-star hotel, Des Milles Collines, who sheltered Tutsis and moderate Hutus who were in danger of being slaughtered.

The current manager, Marcel Brekelmans, says tourists turn up every day to get their pictures taken by the entrance sign, and there is no escaping the country's past.

"It's not only about gorillas and beautiful lakes. Something happened here and everything you encounter here on a daily basis has a history," he says.

Brekelmans, who grew up near one of the largest World War II burial grounds in the Netherlands, says from his perspective, it is necessary to "stop and reflect from time to time".

But how memorials choose to mark such events is a contentious issue.

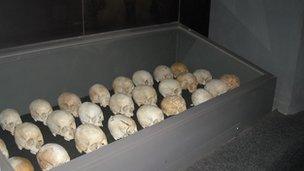

The main memorial in Kigali has cabinets full of skulls, carefully lined up one after another. Other cabinets display pile upon pile of bones.

Similarly, some of Cambodia's memorials to those killed by the Khmer Rouge regime display skulls in a clear pyramid called a stupa.

But exhibiting human remains in this manner is controversial, and a topic that has been debated at length by the very people who oversee such museums.

Some say displaying body parts disrespects the deceased

Dr James Smith is the founder of the Rwandan memorial centre and the UK's Holocaust memorial.

He says when he set up the memorial he worried that displaying skulls recently dug up from mass graves could have threatened the dignity of the deceased.

But he says he decided that it was important to create something where there could be no denying what happened.

As a compromise, Smith uses low lighting to make the display cabinets look like burial chambers.

"In terms of the bones we said, 'instead of stacking them on shelves, [let's] put them in a darkened room, underneath cabinets so it's like a grave that people can look into'," he says.

There have been times when foreign visitors have been insensitive, according to Smith.

He says he had to put up a sign outside the memorial asking people not to stand on the mass graves.

Children and victims' families also visit genocide memorials

So why are tourists increasingly visiting such memorials?

Psychologist Sheila Keegan, an expert in cultural trends, says what people want to get out of a holiday has widened.

While they still want the relaxation they get from sitting on a beach, they also want to broaden their horizons.

"People want to be challenged. It may be voyeuristic and macabre but people want to feel those big emotions which they don't often come across. They want to ask that very basic question about being human - 'how could we do this?'," she says.

Keegan says holidays are also used as a talking point so people want to see something they can discuss when they go home.

"It's about creating your own history, reminding yourself how lucky you are."

But Keegan has a word of caution. She says she didn't give much thought to her own decision to visit Cambodia's "killing fields" and took her daughter there when she was just eight years old because they "happened to be in the country".

She says it is now an experience she regrets.

"I hadn't thought it through. We were in the country so we just went because it was a feature of the country. But I hadn't expected it to be so graphic.

"It was the mid-90s, not long after the civil war. There was still blood on the floor and shackles on the bed."

In the past decade, tourist curiosity about Cambodia's "killing fields" has grown and so-called "dark tourism" is set to become big business.