Treblinka: Revealing the hidden graves of the Holocaust

- Published

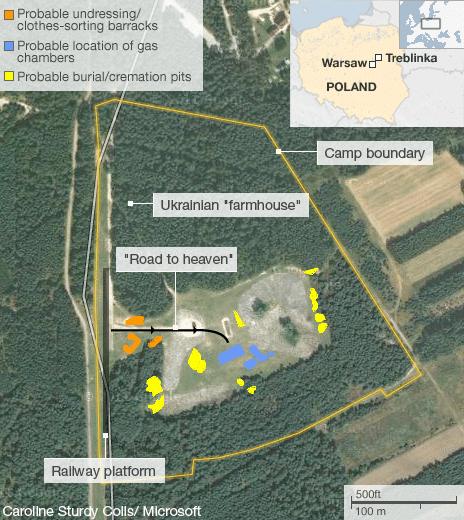

Any doubts about the existence of mass graves at the Treblinka death camp in Poland are being laid to rest by the first survey of the site using tools that see below the ground, writes forensic archaeologist Caroline Sturdy Colls.

When the Nazis left Treblinka in 1943 they thought they had destroyed it. They had knocked down the buildings and levelled the earth. They had built a farmhouse and installed a Ukrainian "farmer". They had planted trees, and - contemporary reports suggest - lupins.

But if they thought they had removed all evidence of their crime, they hadn't. For a forensic archaeologist, there is a vast amount to study.

The destruction of buildings rarely results in the complete removal of all traces of them. And even on the surface there are still artefacts and other subtle clues that point to the real purpose of the site.

A 1946 report by investigators into German crimes in Poland found "a cellar passage with the protruding remains of burnt posts, the foundations of the administration building and the old well" and here and there "the remains of burnt fence posts, pieces of barbed wire, and short sections of paved road".

They also discovered human remains as they dug into the ground, and on the surface "large quantities of ashes mixed with sand, among which are numerous human bones".

Despite this, in a later statement they said they had discovered no mass graves.

The existence of mass graves was known about from witness testimony, but the failure to provide persuasive physical evidence led some to question whether it could really be true that hundreds of thousands of Jews were killed here.

Although they lasted only a few days, those post-war investigations remained the most complete studies of the camp until I began my work at Treblinka in 2010.

This revealed the existence of a number of pits across the site.

Mapping the Treblinka death camp

About 800,000 Jews - almost one in six victims of the Holocaust - were slaughtered at Treblinka between spring 1942 and August 1943

An aerial shot from late 1943, after the camp's closure, shows an empty site, apart from the "farmhouse" (top left) made of bricks from the gas chambers

Victims arrived at a fake railway station, and were made to undress and walk naked to the gas chambers along the "Road to Heaven"

Some may be the result of post-war looting, prompted by myths of buried Jewish gold, but several larger pits were recorded in areas suggested by witnesses as the locations of mass graves and cremation sites.

One is 26m long, 17m wide and at least four metres deep, with a ramp at the west end and a vertical edge to the east.

Another five pits of varying sizes and also at least this deep are located nearby. Given their size and location, there is a strong case for arguing that they represent burial areas.

My research has been designed to respect both the historical and scientific potential of the site as well as its religious and commemorative significance.

No excavation was carried out and the ground was not disturbed, which would be a violation of Jewish law and tradition, banning the exhumation of the dead.

Until relatively recently the technology has not been available to investigate the sites of the Holocaust in such a way.

Aerial photography from the 1940s can now be supplemented with satellite imagery, GPS and mapping software.

A range of geophysical surveying tools also exists, including ground penetrating radar, resistance survey and electrical imaging.

However, no geophysical methods will reveal conclusively what is below the soil - they do not detect human remains.

What each method does is to highlight contrasts between the physical properties of the soil and features within it, such as buried remains or ground disturbance.

Conclusions can then be drawn about the nature of these features by comparing historical and archaeological data, and drawing on knowledge about construction, demolition and burial processes.

As well as the pits, the survey has located features that appear to be structural, and two of these are likely to be the remains of the gas chambers.

According to witnesses, these were the only structures in the death camp made of brick.

Unlike at Auschwitz, there were no purpose-built crematoria at Treblinka.

The decision to burn the bodies of victims was made only after the camp had been operating for several months. The order to exhume and cremate those already buried came in 1943, after the German army had discovered the bodies of Polish officers massacred by the Soviets at Katyn three years earlier - demonstrating to the German leadership the importance of covering up its own crimes.

Witness reports indicate that the bodies were burned on improvised pyres made of railway lines and wood, and the ashes were often reburied in the same graves the bodies had been taken from.

Underground features detected here, coincide with variations in surface level

But recent work in forensic cremation demonstrates that total eradication of bone requires extremely high temperatures. In most crematoria today, bones remain intact and have to be ground down to produce ash.

At Treblinka it is clear that the ash contains many bones. Bone fragments can still be seen on the surface of the ground, especially after rain.

Considerable evidence also exists to suggest that not all of the bodies were exhumed and cremated. Photographs show bodies littering the landscape as late as the early 1960s.

But this work is just the beginning and further work is required to understand the complexity of the site.

This initial survey should be viewed as a start of what will hopefully be a long-term collaboration between myself and the Treblinka museum, aimed at providing new insights into the physical evidence, and allowing the victims of the Holocaust to be appropriately commemorated.

The Hidden Graves of the Holocaust will be broadcast on Monday 23 January at 20:00 GMT on BBC Radio 4