A Point of View: The many faces of Margaret Thatcher

- Published

- comments

Britain's Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was a decisive and divisive figure, loved and hated in equal measure. Is the complex character behind the Iron Lady facade obscured behind reminiscences fond and hostile, asks historian Lisa Jardine.

Just before Christmas, The National Archives (of which I recently became a director) released its annual set of documents under the 30-year rule, to the year 1981.

This is when hitherto-restricted government papers disclose secret detail about recent historical events.

Among those published this time were several giving intriguing behind-the-scenes insights into Margaret Thatcher's thinking and decision-making shortly after she became Conservative prime minister in 1979.

On 16 May 1979 - less than two weeks after the election - Peter Walker, Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, wrote to Chancellor Geoffrey Howe, urging him to raise the then state-controlled retail price of milk by 1.5p to 15p a pint - a more than 10% increase.

"I find we have inherited from the Labour government a difficult situation in relation to the retail and wholesale prices of milk," Walker wrote.

"If we do not act quickly, I fear the whole industry will begin to doubt the strength of our commitment to ensuring the health of farming."

The Prime Minister disagreed strongly.

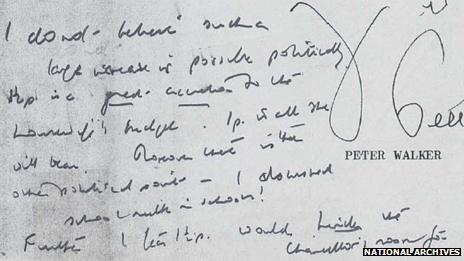

Across the bottom of Walker's typed letter to Howe, she scrawled in her highly recognisable handwriting: "I do not believe such a large increase is possible politically. 1.5p is a great addition to the housewife's budget. 1p is all she will bear.

"Moreover there is the other political point - I abolished school milk in schools!"

Margaret Thatcher's hand-written note about milk prices

Here, we surely detect the woman rather than the prime minister speaking, alert to imputations of lack of housewifely concern.

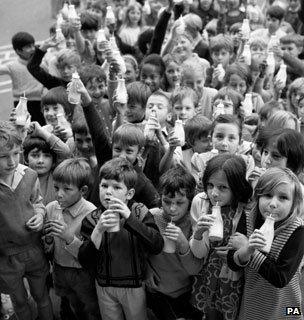

In April 1971, when she was Education Secretary in the Edward Heath government, she had indeed been responsible for abolishing free school milk for the over seven-year-olds - earning her the enduring derogatory nickname "Maggie Thatcher, milk snatcher".

Daily free milk was once a schoolyard staple

In 1979, in spite of her qualms, the new government did increase the price of milk by 1.5p, and again the following December.

On both occasions the press, as Thatcher had anticipated, made much of what they regarded as the mismatch between the fact that, as a woman, she could be expected to show concern for children, nutrition and the housekeeping budget, and the fact that her public statements on both occasions firmly defended the policy.

Last Tuesday, following the announcement of the 2012 Academy Awards nominations, Meryl Streep became the bookies' favourite to win this year's best actress award for her portrayal of Margaret Thatcher in Phyllida Lloyd and Abi Morgan's acclaimed biopic, The Iron Lady.

Critics are agreed that Streep's is an impressive performance, with (some have even maintained) the tragic intensity of King Lear.

As in Lear, the action is focused on old age - three days in 2005, when, aged 80, Thatcher's faculties are failing and she struggles to come to terms with the life she has lost - vividly recalled in flashback - including the lost companionship of her husband Denis, who died in 2003.

Meryl Streep: "I wanted to capture whatever it was that drew people to her or meant people have a special venom for her"

I found The Iron Lady a compelling watch. I was on the edge of my seat emotionally throughout.

Meryl Streep's portrayal of Britain's first woman prime minister is a tour de force, and not simply as an impersonation. Thatcher in old age is unknown to most of us, so Streep's representation of the former prime minister is largely her creation. Streep's Mrs Thatcher is a figure almost shockingly available for our scrutiny - for much of the time in close-up, tempting us to try to read from the intensity of her screen presence the paradox of the passionate woman behind the iron mask.

Morgan's screenplay and Lloyd's direction embed Streep's performance in a beautifully observed collage of public and private moments from Thatcher's life, captured with deft, subtle cinematographic touches.

When the young Denis Thatcher proposes in 1950, just after Margaret has failed to win her first parliamentary seat at Dartford, she tearfully insists that she will "never be one of those women remote and alone in the kitchen doing the washing up".

Meryl Streep as Margaret Thatcher

She has to make a difference to the world: "I cannot die washing up a tea cup". The film's final scene shows her, frail and confused, slowly washing the teacup from which she has just drunk her mid-morning cup of tea.

And the first words she speaks as the film opens - returning from an excursion to the local convenience store, evading her carer and minders, to buy a pint of milk - studiedly recall her two unpopular political brushes with the nation's milk supply.

"Milk's gone up. 49p a pint," she observes across the breakfast table. "Good grief!" retorts husband Denis (actually deceased, and a figment of her imagination). "We'll have to economise."

And yet I found the film troubling.

The 11 years of Margaret Thatcher's premiership were some of the most turbulent I and my like-minded contemporaries lived through. At the time we were opposed to almost every political decision she ever took.

Opinion in the country was sharply divided, of course, hence her victory in three general elections.

She served three terms as prime minister

But we supported the miners in the miners' strike, we were opposed to the Falklands War, horrified by the sinking of the Belgrano. We could hardly believe the unfairness of the proposed per capita poll tax. ("In order to live in this country you must pay for the privilege. If you pay nothing, you care nothing," is Thatcher's characteristically blunt justification in the film.)

What am I to do now with an insightful portrait of the complex personality with its hopes and fears, self-doubts and uncertainties, behind the decisive and politically robust facade? Nothing is thereby altered in the consequences of her sometimes inflexible policies.

My ambivalence about The Iron Lady returned me to a thought I have been turning over in my mind for some time. In the course of my Points of View, I have several times revisited the subject of my beloved paternal grandmother.

Here is how I recalled her in 2007, external when speaking about the important example she set me in my life: "I remember my paternal grandmother - a formidable woman, with a razor-sharp intellect and an iron will - as permanently exasperated at the absence of any real role for her outside the domestic.

"By the time I knew her, poor health had confined her to the housekeeping, where she was only happy when performing a really difficult task with panache. I have a vivid mental picture of her with a smile of satisfaction on her face as she whipped two egg whites into stiff, brilliant white peaks to make meringues, on a flat dinner plate with an ordinary fork, the eggs held on the angled plate by the sheer force of her beating."

Eric Taylor of Sheffield, however, who as a young Labour Party activist had encountered my grandmother in political circles in London's Stamford Hill, was not impressed by my sentimental recollections of Mrs Bronowski.

"You described your grandmother as 'a formidable woman', he wrote to me after my meringue-whipping reminiscence. As someone who had the misfortune of encountering her, I'd describe that as a considerable understatement.

"You referred to her being 'active in local politics'. However, you carefully refrained from mentioning that she was a rabid and fanatical communist, whose only response to anyone who disagreed with her was to hurl a stream of invective and personal abuse at them. I do not think you should allow personal sentiment to prevent you from acknowledging that some aspects of your grandmother's personality, political outlook and career may have left something to be desired."

So have I skewed the historical record with my fond reminiscences of my grandmother?

Did I, perhaps, choose deliberately to omit the fact that she had been active in far-left politics during and after World War II and had stood as a Communist candidate for the London County Council?

I don't think so. My grandmother's legacy went no further than her private life and the model she served as for me, her eldest grandchild.

The Iron Lady became a Baroness

By contrast, whether we supported or opposed her during her years in power, Margaret Thatcher's legacy continues to shape the society in which we live today.

In the opening shots of The Iron Lady, as Thatcher wanders incognito around her local corner-shop, a man on a mobile phone pushes past her to the front of the queue. She is jostled by a young man engrossed with his iPod.

The film hints here that Britain is tougher and less considerate than in the days of Thatcher's confident individualism. "There is no such thing as society," Mrs Thatcher told Woman's Own in 1987. Each of us has to look out for ourselves, not expect "society" to take care of us.

For some of us, that is as much Margaret Thatcher's legacy as the contribution her years in power made to the relative financial strength of our economy today.

- Published5 December 2011