Melting down hips and knees: The afterlife of implants

- Published

- comments

As people live longer and medical technology improves, more and more of us will have a surgical implant before we die. We are also getting cremated in larger numbers - and so there is often some expensive metal left among the ashes. Where does it go?

"You tell people what you do, and they think... well, that's a bit strange," says Ruud Verberne above the din of giant sorting machines twirling and clanking.

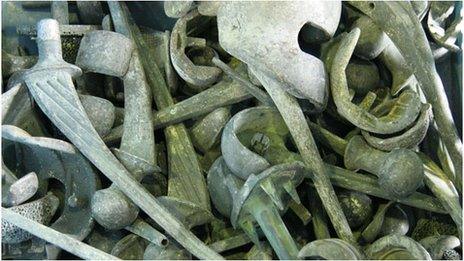

Verberne is co-founder of OrthoMetals, which recycles metal implants from cremated human bodies. That's everything from steel pins to titanium hips and cobalt-chrome knees.

These are the knees that we have to recover," he says. "Some metals can be sorted by magnets. And the remaining have to be sorted by hand."

Strange it may be, and a bit macabre perhaps, but this kind of recycling is a growth industry.

"I know the existence of five or six competitors that we have, most of them in the United States," says Verberne, whose company is based in the Dutch city of Zwolle. "But we were first."

Verberne had a long career in aluminium recycling. Then, in 1987, he met Jan Gabriels, an orthopaedic surgeon, who asked him what happened to the metal implants he spent his working life attaching to patients.

Verberne had no idea, so he did some research and he found out that they were thrown away. "They were basically buried," he says.

The value of implants collected from a crematorium is only a fraction of their value before surgery, but they are made from good quality metal that is worth recycling.

"The operation to provide a new hip may cost you around £5,000 ($8,000. 6,000 euros)," he explains.

"But the return value as scrap is maybe, per kilo, around £10 ($16, 12 euros). And there are five hips per kilo!"

In 1997, Gabriels and Verberne founded OrthoMetals. Fifteen years later the company recycles more than 250 tons of metal from cremations annually, which gets used to make things like cars, planes, and even wind turbines.

The company works by collecting the metal implants for nothing, sorting them and then selling them - taking care to see that they are melted down, rather than reused.

After deducting costs, 70-75% of the proceeds are returned to the crematoria, for spending on charitable projects.

"In the UK for example," he says. "We ask for letters from charities that have received money from the organisation we work with in the UK and we see that the amount we transferred to them has been given to charity. This is a kind of controlling system that we have."

Henry Keizer oversees a charitable memorial fund named after the first Dutch person ever cremated - a Dr Vaillant - back in 1913.

He says the fund has helped Dutch crematoria distribute money received from OrthoMetals to support everything from cancer research to school libraries.

"I think the recycling of implants, and artificial joints, is an excellent idea," he says. "Now we get to use them for good purposes, for funds for people that do social things that are extremely important."

Michael Donohue, director of the Donohue Funeral Home in the US state of Pennsylvania, found OrthoMetals through a Google search, when the home recently built its own cremation facility.

"Before we actually started to get up and operating, our biggest thing was - what are we going to do with the metal remains that are left at the end of the process?" says Donohue.

Now, recovered surgical implants go back to Holland for recycling.

Donohue says his staff are candid with loved ones about this. "We are honest with them, and tell them that whatever money is given to us goes to local organisations, and they love knowing that something from their loved one is being used in a great capacity."

Relatively few people are cremated in the US by international standards - the figure currently stands at 40%, though the trend is upwards and there are some big geographical variations.

Recent figures show Hawaii and Nevada up near 70%, but Mississippi at less than 10%. That could be a mark of socio-economic status, says Verberne. Statistics tend to show poorer people prefer in-ground burials.

In Verberne's native Holland, some 57% of all bodies are cremated. Britain is the biggest cremator in Europe with 73%. And since the Catholic church eased its opposition to cremation, the company has seen growth in places such as Italy and Spain. In all, it operates in 15 countries.

He has some thoughts on why cremation rates are increasing in many parts of the world.

"Two reasons are space and cost," he says. A traditional burial can cost four times as much as cremation. And regarding space, one survey showed 750 burials taking up an acre of ground.

Verberne also identifies some cultural changes. "In earlier days the family would visit a grave to see dad or mum," he says. "Nowadays they scatter the ashes and they are free. They want no obligations."

Mr Verberne has no metal implants himself, but he points out his business partner's wife, who is helping sort out bits of metal at the recycling plant.

"She has two titanium hips", he says. "And she was once asked: "Isn't it strange that you know that one day your hips will run along this conveyor belt?'"

"She said, 'No, it's just a part of life. You're going to die, and I know that reusing metals is a very good thing, so it is no problem at all.'"

She added "'My mother's hip was on here too!'"

Listen to more on this story at PRI's The World,, external a co-production of the BBC World Service, Public Radio International, and WGBH in Boston.