Townsend Griffiss, forgotten hero of World War II

- Published

It's 70 years this week since the first US air force officer was killed in Europe, following America's entry into World War II. By heading the list of 30,000 USAAF men to lose their lives in the European theatre, Lt Col Townsend Griffiss became a footnote in the history of the war. But who was he and how did he die?

There is no memorial to Townsend Griffiss in the UK, but a corner of Bushy Park in west London offers the faintest of reminders.

Here, half covered by grass, are a handful of tablets in the earth, marking the various blocks of Camp Griffiss, the British headquarters of the US Army Air Force, set up in the summer of 1942. It's a royal park, and the royal deer help prevent the plaques disappearing into the grass entirely.

Overhead, civilian airliners pass by on their way towards nearby Heathrow. From above, the outlines can also be made out of some of the wartime buildings where up to 3,000 US and British servicemen and women toiled in the months before D-Day.

The last buildings disappeared in the early 1960s, and another half a century on, the name Griffiss does not mean much to a Londoner. But the fact that the camp was given his name - along with another airbase in upstate New York a few years later - indicates how highly he was regarded by the US military.

At the time of his death on 15 February 1942, he was 41 years old, a high-flying officer, returning from the Soviet Union, where he had been sent on a diplomatic mission by US Army Chief of Staff Gen George Marshall.

He had earlier been one of the sharpest observers of the Spanish Civil War, sending home crucial information about the capability of German, Italian and Russian aircraft, analysing the role these new forces were playing in the conflict, and forecasting the role they would play in future wars.

In mid-1941, he was one of the first US officers sent over as "special observers" to London - officially neutral, but in reality preparing the ground for the military alliance that would become public after Pearl Harbor.

In photographs, there is a mischievous glint in his eye, and on his lips, very often, a textbook example of a half smile.

The impression that he was a man who knew how to enjoy life is confirmed in a guidebook to Hawaii he wrote in the 1920s, external, full of references to bronzed Dianas and Apollos and the strumming of ukuleles, and occasional allusions to a girlfriend named only as EW.

Written during his stint as a fighter pilot on the islands from 1925 to 1928, it makes no explicit mention of his day job, but drops a few hints.

"I dare say that very few have ever had the privilege of spending a morning at an Air Corps Flying Field, especially at one having so important a function as Wheeler Field, the home of the 18th Pursuit Group," he writes, tongue possibly in cheek.

He also suggests a trip to the islands' other main flying base, Luke Field, adding: "If you contemplate such a visit, I suggest that you call the adjutant."

Griffiss himself served at both fields at one time or another, and for a while as adjutant. When he wrote those words, he may have in effect been telling readers to call himself.

During his period on the islands, he notes, beachwear became more and more daring, until "ninety-nine hundredths stripping" became acceptable.

At an early stage, he writes, "I became obsessed with the idea of acquiring a coat of tan from the top of my head to the tip of my toes." He set out for the then remote spot of Hanauma Bay, only to find, when he reached the final brow and looked down on the beach, a huge Hawaiian family picnic under way.

"Disillusioned, furious and reckless," he writes, he drove back to Waikiki and "helped start the... fashion" for near-nude bathing.

Griffiss had been brought up in a wealthy family in Coronado, the exclusive beach suburb of San Diego in California.

George Patton instilled Hawaii's Army polo team with "fighting spirit"

His stepfather, Wilmot Griffiss, was head of the bond department for a leading San Diego bank. His mother, Katherine Hamlin, was a daughter of one of Buffalo's richest men - a horse-breeding sugar magnate - who eloped (as a local newspaper put it, external) with a wealthy businessman's polo-playing son, Ellicott Evans.

Griffiss's mother and stepfather mixed in West Coast high society. His sister, meanwhile, lived next door to the future Wallis Simpson and her first husband, Earl Winfield Spencer, first commander of Coronado's Naval Air Station, and both couples attended a party held for the Prince of Wales when he toured the West Coast in 1920.

It was thanks to his family's wealth that Griffiss, generally known as Tim rather than Townsend, was able to hire a house within yards of Waikiki beach in Honolulu, and to indulge an expensive passion inherited from his father - polo. The Army team on Hawaii was trained and led by George S Patton, then a major, but later the general whose tanks stormed out of Normandy breaking all records for liberating territory and capturing enemy divisions.

"The Major has incited that old fighting spirit which carries the team with a rush to the last gong," writes Griffiss - again, without explaining to readers his personal link to the events described.

When, after stints at airfields in California and Texas, Griffiss was sent to Washington DC in 1933, he arrived - to the delight of his two nephews - with three polo ponies. On Sundays the boys went to Fort Myer, near Arlington Cemetery, where the ponies were stabled, and helped to exercise them.

"Where Washington National Airport now is there was a big marsh with lots of trails across it that we used for our rides," recalls retired Naval Captain Richard Alexander, who was given the middle name Griffiss in honour of his mother's stepfather.

"We had a spoilacious relationship with Uncle Tim. It was easy to become terribly attached to this exciting, dynamic figure."

Griffiss's private income also helped to set him up for his next job as an assistant military attache for air in Paris, Berlin and Spain.

The qualities selectors took into account included tact, personality and personal appearance, according to a 1938 study by students at the Army War College, and also financial status - as attaches had to maintain a lifestyle their salaries would not support.

Arriving in Europe in 1935, Griffiss spent most of his time from 1936-1938 observing the civil war in Spain at close quarters.

"The undersigned was fortunate in having spent the night of July 11-12 at his beach house near Perello," he writes in one despatch, adding that it gave him a bird's-eye view of a naval engagement between a cruiser loyal to Gen Franco, and three government destroyers.

But it was in his observations of the war in the air that he excelled.

The conflict in Spain was widely seen as a test-bed for military technologies that would decide the next world war and the US Military Intelligence Department was hungry for information about how aircraft and tanks were employed, and how well they performed.

Griffiss supplied detailed and thoughtful despatches, sufficient to fill a whole book, according to one commentator, external.

US diplomats had better contacts with the Soviet-backed Spanish government forces than with Franco's nationalists, so Griffiss resorted to unusual measures to gather information about the new German planes, according to his nephew.

"He convinced them to loan him a Russian fighter plane so he could go up and see what the new Messerschmitt 109s had in them," says Capt Alexander.

"He tangled on several occasions with the prototypes of the Me 109, which must have given him good information to post back to this country."

One of the lessons Griffiss drew was that work needed to be done to develop air forces suited to working in close co-ordination with commanders on the ground.

Another was that the fashionable theory that powerfully armed bombers could win a war by themselves was a mistake.

Bombers, at least in the limited way they were being used in Spain, did not cause public panic, he noted. He also concluded that fighters would always be necessary to protect bombers and would "remain the decisive factor" in air supremacy.

The "flying fortress" idea had died in Spain, he and military attache Stephen Fuqua wrote in 1937, to the irritation of some leading Air Corps figures in Washington.

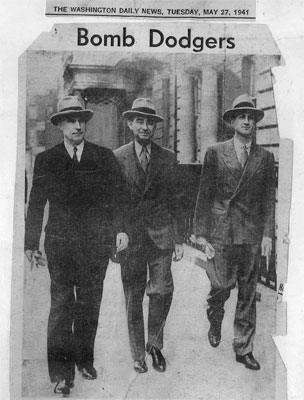

Griffiss (right) arrived in London at the tail end of the Blitz, as an aide to General James Chaney (left)

The war in Europe began five months after the end of the Spanish Civil War. For the first two years the US remained officially neutral, but in September 1940 it agreed to a crucial deal - described by Winston Churchill in his memoirs as "decidedly unneutral" - to provide Britain with 50 badly needed naval destroyers, in return for the lease of military bases in a range of British territories.

It was this deal that gave Winston Churchill his cue to tell parliament that "these two great organisations of the English-speaking democracies, the British Empire and the United States... will have to be somewhat mixed up together in some of their affairs, for mutual and general advantage."

He went on:

"For my own part, looking out upon the future, I do not view the process with any misgivings. I could not stop it if I wished. No-one could stop it. Like the Mississippi, it just keeps rolling along. Let it roll. Let it roll on - full flood, inexorable, irresistible, benignant, to broader lands and better days."

It's impossible to know whether Townsend Griffiss had any misgivings about this process, but it formed the backdrop for the last 18 months of his life.

He first acted as an adviser from the Air Corps to the US admiral sent to the Caribbean to select the locations for military bases on Bermuda and five West Indian colonies. The wrangling over some of these bases went on until the spring.

Then in May 1941 he was sent to London as part of a special observer group (Spobs). This was a military mission by another name. Its members wore civilian clothes, but formed the nucleus of a joint military planning staff, along with a parallel British military mission in Washington. Griffiss was aide to the man in charge in London, Gen James Chaney.

As well as holding regular meetings with the British operational planning staff, Spobs had to arrange for the pre-agreed American occupation of Iceland, and oversee the construction of naval and air bases in Northern Ireland and Scotland, for the use of US forces if and when they entered the war.

But in November Griffiss was detached from Chaney's staff and sent to Moscow, to negotiate with the Soviet government about the opening of a Siberian supply route for American lend-lease aircraft.

American aircraft were being sent to the USSR on Arctic convoys from the UK. They could also be flown to the USSR via the Middle East, but a route from Alaska to Siberia made more sense. Soviet diplomats in Washington gave assurances that Moscow was ready to help set up the delivery route, but embassy staff in Moscow were stonewalled whenever they raised the subject.

Gen George Marshall sent Griffiss to sort it out. He spent about two months in the Soviet Union trying to get straight answers, first in Moscow, then, when German forces reached the outskirts of the city, in Kuibyshev, the temporary wartime capital.

According to John Alison, then attached to the US embassy in the Soviet Union and later one of the fathers of US Air Force special operations, Griffiss got nowhere. "The Russians were just running us around in circles," he recalled, years later, external.

The UK's first B-24 Liberators were used for civilian flights and coastal patrols rather than bombing

Cold weather delayed Griffiss's departure. From Kuibyshev he went to Tehran, and from Tehran to Cairo, where he boarded an unarmed B-24 Liberator operated by the British Overseas Airways Company (BOAC) for a direct flight to the UK.

The flight was the first of its kind. The outward journey had been made on 24 January but strong headwinds repeatedly delayed the return trip. In such conditions, the Liberator would have run out of fuel on the traditional route across the Bay of Biscay around Brittany and and along the English Channel from the west.

The captain, Humphrey Page, therefore suggested a direct route across occupied Europe at night.

The Air Ministry in London signalled approval for the route. But conflicting messages were received from RAF Transport Command, which was against it, and from BOAC which appeared to be in favour. After asking BOAC to confirm its position, and getting no reply, the Liberator took off on the evening of 14 February.

The next morning as it reached the coast of northern France, near St Malo, the aircraft appeared on British radar screens, initially registering as hostile. Two Spitfires from a Polish Air Force squadron in Exeter were sent to investigate. As they closed in on the grey-coloured aircraft, one pilot saw a bright flash coming from a glass turret. At the same time - he told the subsequent inquiry - the aircraft turned and began to dive into cloud.

Both Spitfires opened fire, the Liberator's right engine was hit and started smoking, and it disappeared from view. Shortly afterwards, emerging beneath the cloud, the pilots saw a large patch of oil and disturbed water.

Among the remains recovered were some socks belonging to the flight's first officer, some bags of diplomatic mail - which should have sunk, but for some reason floated - and a leather bag belonging to Griffiss.

The court of inquiry blamed the Spitfire pilots, Stanislaw Brzeski and Jan Malinowski for failing to identify the Liberator as a friendly aircraft before opening fire, and recommended a court martial - but it was later decided there was insufficient evidence to proceed.

Controllers who knew that a Liberator would be arriving on a path over occupied France on the morning of 15 February were also reprimanded for not warning the Exeter fighter sector.

The question why the Liberator was not immediately identified on radar screens as a friendly aircraft went unanswered - either its friend-or-foe identification transmitter was not working or it was not switched on.

The flashes of light from the Liberator were assumed to be a Morse-code message flashed from an Aldis lamp. But technically the Liberator should have signalled its friendly status by firing a colour-coded flare.

One of the key lessons learned from the tragedy was that fighter pilots needed better instruction in the recognition of aircraft - both military and civilian.

"In view of the important personages carried in civil aircraft, more attention should be paid to the identification of civil aircraft," the court of inquiry recommended.

The B24 Liberator was to become one of the most familiar heavy bombers operated by US airmen in Europe, but in February 1942 there were not many around.

Stanislaw Brzeski, the first of the Spitfire pilots to shoot, told the inquiry he had never seen a Liberator before. He mistook it for a German Focke-Wulf 200, another four-engined aircraft, usually grey in colour.

The dead comprised five crew members and four passengers - Griffiss, a brigadier of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, a Navy lieutenant and a Rolls Royce employee.

In the Air Ministry there was great embarrassment. An approach was made to Air Chief Marshal Charles Portal to write to Gen Chaney, to "ease what may be a difficult and delicate situation to overcome".

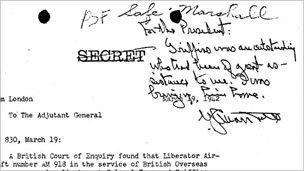

Gen George Marshall made clear to President Roosevelt how deeply he felt Griffiss's loss

In his letter, Portal offered his deepest sympathy, adding that the Air Staff would feel Griffiss's loss acutely.

"He was a personal friend of many of them, and no-one could have been a more helpful collaborator," he wrote.

Chaney later communicated the outcome of the court of inquiry to Washington, asking for there to be no publicity.

In a message to President Franklin Roosevelt written by hand on the top of Chaney's message, external, Gen Marshall described Griffiss as an outstanding officer. "I was bringing him home," he said.

Griffiss received the Distinguished Service Medal posthumously for his work in London and in the USSR. The citation said he displayed "rare judgement and devotion to duty" and "contributed materially to the the successful operation of the Special Army Observers Group, London".

Just months after Griffiss's ill-fated trip to the USSR, when Britain's hold on Egypt appeared to be weakening and the lend-lease supply route via the Middle East seemed in danger, the Soviet authorities abruptly took a brighter view of the Alaska-Siberia route he had been trying so hard to open up. Starting that summer it became the major pathway for US aircraft deliveries to the Soviet Union - with Soviet pilots collecting the planes from Alaska and flying them home.

But if that story quickly acquired a happy ending, members of Griffiss's family lived with their loss for years. His mother died in 1951, while his sister Elizabeth and her husband, Rear-Admiral Ralph Alexander, who had been close to Griffiss, lived until 1982 and 1970 respectively.

Captain Richard Alexander, now 89, remembers hearing the news of the accident. He and his brother Bill, both studying at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, were summoned to the telephone in the middle of the night to receive a call from their father.

"We heard dad on the phone telling us about Tim's loss. I was probably emotionally closer to Tim than my brother and it was quite a blow," he says. "I can remember those hours very clearly."

After the war, he named his son, Townsend Griffiss Alexander. Now a rear-admiral commanding the US Navy's Mid Atlantic region, he too, like his namesake, is generally known as Tim.