When Charles Dickens fell out with America

- Published

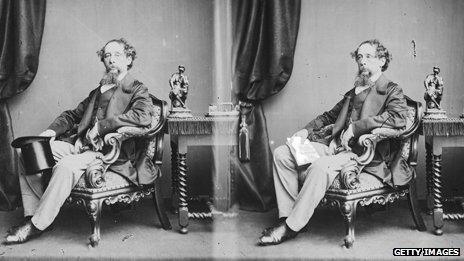

Photography was in its infancy in the 1840s. These portraits date from 1860

On his first visit to America in 1842, English novelist Charles Dickens was greeted like a modern rock star. But the trip soon turned sour, as Simon Watts reports.

On Valentine's Day, 1842, New York hosted one of the grandest events the city had ever seen - a ball in honour of the English novelist Charles Dickens.

Dickens was only 30, but works such as Oliver Twist and the Pickwick Papers had already made him the most famous writer in the world.

The cream of New York society hired the grandest venue in the city - the Park Theatre - and decorated it with wreaths and paintings in honour of the illustrious visitor.

There was even a bust of Dickens hanging from one of the theatre balconies, with an eagle appearing to soar over his head.

Dickens and his wife, Catherine, danced most of the night in the company of around 3,000 guests.

"If I should live to grow old," the novelist told a dinner the following night, "the scenes of this and other evenings will shine as brightly to my dull eyes 50 years hence as now".

But a visit which had started so well quickly turned into a bitter dispute, known as the "Quarrel with America".

Enthusiastic fans

As a committed social reformer, Dickens wanted to use his trip to find out if American democracy was an improvement on class-ridden Victorian England.

The novelist particularly enjoyed Boston, his first port of call.

His hosts watched in amazement as he charged through the snowy streets with delight, reading aloud the signs on the shops.

But little by little, the enthusiasm of his American fans began to overwhelm him.

When Dickens's boat made a stopover in Cleveland, he awoke to find a "party of gentlemen" staring through the cabin window as his wife lay in bed.

"If I turn into the street, I am followed by a multitude," Dickens complained in a letter.

"I can't drink a glass of water, without having 100 people looking down my throat when I open my mouth to swallow."

'Fellow animals'

The novelist was particularly irritated by Americans who tried to make money out of his fame.

In New York, the jewellers Tiffany's had made copies of a Dickens bust and an enterprising barber is said to have tried to sell locks of the writer's hair.

Then, there were the table manners of the Americans that Dickens was forced to share meals with as he travelled around the country.

In his travel book, American Notes, Dickens describes Mid-Westerners at dinner as "so many fellow animals", who "strip social sacraments of everything but the mere satisfaction of natural cravings".

"The longer Dickens rubbed shoulders with Americans, the more he realised that the Americans were simply not English enough," says Professor Jerome Meckier, author of Dickens: An Innocent Abroad.

"He began to find them overbearing, boastful, vulgar, uncivil, insensitive and above all acquisitive."

'Tobacco-tinctured saliva'

Dickens had scheduled a whole week in Washington to see if American politics lived up to his high hopes.

Martin Chuzzlewit was written after Charles Dickens returned to England from his North American trip

He visited the Capitol, met American politicians and attend President John Tyler's morning reception at the White House.

But by now Dickens was in such a foul mood that his enduring memory of the city was the tobacco-spitting he saw in the streets.

"Washington may be called the head-quarters of tobacco-tinctured saliva," Dickens fumed in American Notes. "The thing itself is an exaggeration of nastiness, which cannot be outdone."

As for the politicians, Dickens concluded that, like everyone else in America, they were motivated by money, not ideals.

"I am disappointed," he wrote in a famous letter. "This is not the republic of my imagination."

Washington, Dickens blasted in American Notes, was the home of: "Despicable trickery at elections; under-handed tamperings with public officers; and cowardly attacks upon opponents, with scurrilous newspapers for shields, and hired pens for daggers".

Pirated editions

By this stage in the trip, Americans were as annoyed with Dickens as the novelist was with them.

The issue was a very modern one - intellectual property.

In 1842, there were no international copyright laws so Americans could read Dickens's works for free in pirated editions.

Once Dickens saw how popular he was in the US, he realised he could virtually double his income if his American fans started paying a going rate for his work.

"I am the greatest loser alive by the present law," he complained in letters home.

Dickens raised the matter with his American audiences as tactfully as he could.

At literary dinners, he argued that a copyright law would help American writers as much as him, and he stressed that he would "rather have the affectionate regard of my fellowmen as I would have heaps and mines of gold".

But the American press turned on Dickens, accusing him of mixing pleasure and business.

"We are mortified and grieved that he should have been guilty of such great indelicacy and impropriety," said the New York Courier and Enquirer, then the country's most popular paper.

"The entire press of the Union was predisposed to be his eulogist, but he urged those assembled (not just to) do honour to his genius, but to look after his purse also."

Dickens's visit to America ended with both sides accusing each other of being vulgar money-grabbers.

'Traitor'

On his return to England, Dickens published two books about his American trip.

As well as the scathing travel writing of American Notes, he satirised the country viciously in a section of Martin Chuzzlewit, his next major novel.

To the American press, the books were a libel on their country.

"We are all described as a filthy, gormandizing race," raged an article in the Courier and Enquirer, which was edited by James Watson Webb.

It described Dickens as a "low-bred scullion... who for more than half his life has lived in the stews of London".

Many of the friends Dickens had made in America, such as the novelist, Washington Irving, were also outraged and struggled to forgive him for ridiculing their country in print.

"Americans felt they'd welcomed Dickens into their country as a hero," says Prof Meckier, "and now there was a sense he was a traitor."

'Silver sunshine'

For some Dickens scholars, the "Quarrel With America" marks a significant shift in his work.

"Dickens had a traumatising experience in America," argues Prof Meckier. "He became less radical, less optimistic, and he downgraded his view of human nature."

Dickens expressed his darker world view in later novels such as David Copperfield and Bleak House.

But despite the "quarrel", these books sold as well as his early works. And it was the novelist's enduring popularity with American readers that eventually ended the dispute.

Towards the end of his life, Dickens began holding wildly popular public readings from works such as A Christmas Carol.

He sent a scout to assess if the American public would react as well as his fans in England, and after getting favourable reports, he returned to the US in 1867 and 1868.

Dickens needn't have worried about his reception.

"To say that his audience followed him with delight hardly expresses the interest with which they hung upon his every word," wrote the Boston Journal.

"It was not Dickens, but the creation of his genius, that seemed to live and talk before the spectators."

Almost all of Dickens's American critics were won over by his performances, and the quarrel was declared to be over.

"Dickens' second coming was needed to disperse every cloud and every doubt," said the New York Tribune, "and to place his name undimmed in the silver sunshine of American admiration".

- Published7 February 2012