Is Greece's the longest recession in history?

- Published

Greece is in the midst of a recession that has been described as the longest ever recorded. Is that correct?

The hardship suffered by the Greeks is evident in the jobless queues, the beggars and the rough sleepers.

According to one senior minister, the country's plight is as bad as any depression.

"We are expecting 2013 to be the sixth consecutive year in recession," says Notis Mitarakis, Greek shadow finance minister. "I don't think there's any other historical record of any country being six years in recession."

So how does Greece's ordeal compare with other downturns?

Economists differ over the definition, but a recession is commonly regarded as two consecutive quarters of negative growth (a fall in gross domestic product, GDP).

Given the lack of reliable data, no-one could ever identify with certainty the longest recession in history, but there have been some notable examples.

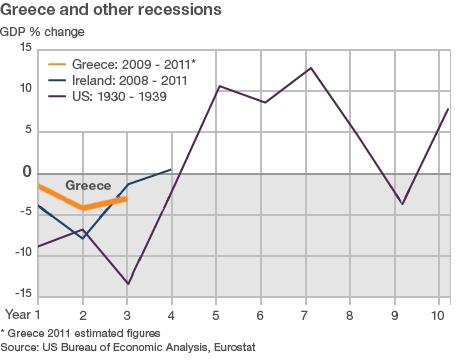

Greece and Ireland, 2000s

According to the Greek government's own figures, the economy first contracted in the final quarter of 2008 and - apart from the odd quarter of weak growth - has been shrinking since.

This puts it in its fourth year of recession, although if you interpret the odd spurt of growth as the end of a recession, Greece has emerged from recession more than once and gone straight back in.

But the World Bank says the country had its first full year of recession in 2008, which makes 2012 - as the minister claimed - the fifth year.

Ireland's economy first contracted in 2006, two years before Greece, and has had more quarters of negative growth than Greece, but the severe austerity programme in store for Athens suggests it will be some time before Greece recovers.

Dr Richard Wellings, deputy editorial director at the Institute of Economic Affairs, says GDP figures should always be treated with caution because they are revised and amended for years afterwards.

"Greece had positive growth [overall] in 2008 so we're only looking at just over three years - 2009, 2010 and 2011 [so far]. But at best it's going to be stagnant in 2013. If it leaves the euro, there's a stronger chance of GDP growth in 2013 because that would enable a rapid adjustment process, although it would be a short, sharp shock."

So even if Greece turns the corner, it is likely to have spent more than five full years with a shrinking economy, before the economy recovers.

The US, 1930s

The Great Depression in the US has been a common reference point for commentators discussing the latest financial crisis.

The Dust Bowl drove thousands of families out of Oklahoma

The US Bureau of Economic Analysis only began collecting GDP data in 1930, the year after the Wall Street Crash, and it says the US economy contracted for four consecutive years. Its GDP fell by nearly a third.

The contraction in the US was more severe than in Greece, says Mr Wellings, so the two recessions are not yet comparable.

"It was also a double dip because it went back in [to recession] in 1937-38. So it recovered strongly but went back into recession."

But if you just took the two private sectors - Greece today and the US then - then the contractions are probably similar, says Mr Wellings, because Greece's public sector is so much bigger than the US's was in the 1930s.

The US, 1870s

Perhaps even longer than the slump of the 1930s was the Long Depression of the 1870s, which was called the Great Depression until the other one came along 60 years later.

It brought down the US bank Jay Cooke & Company and was sparked by a financial panic in Europe.

The US National Bureau of Economic Research estimates that the US economy was contracting for 65 months, from October 1873 to March 1879, 22 months longer than the Great Depression of the 1930s.

But Albrecht Ritschl, a professor of economic history at the London School of Economics, says the severity of this depression has been re-evaluated in recent years.

"It used to be the depression that everybody had on their minds but then there were data revisions and scholars became less sure of it," he says. "It's like a Flying Dutchman, it's elusive."

Tajikistan, 1990s

One of the most prolonged downturns in recent years took place in Tajikistan which, according to the World Bank, endured nine years of minus growth from 1989 onwards.

Food became scarce after independence

John Heathershaw, author of Post-Conflict Tajikistan, says the years were characterised by a civil war, a humanitarian crisis and the long, painful transition from a command economy to a market economy. But the figures should be treated with caution, he says.

"The civil war began in May 1992 so prior to that there was economic decline across the Soviet Union and that hit Tajikistan worst. Out of all 15 [Soviet] republics, it was the most dependent on Moscow for direct transfer of resources."

It is estimated that independence in 1991 reduced the country's GDP by 50% overnight, he says, but accurate data before and after that date is very difficult to find.

"I've sat in [government] meetings in the 2000s and there was a lot of guesswork."

At least half the economy is thought to be the black market, he says, and Tajikistan is the most remittance-dependant economy in the world, reliant on the wages of migrants in other parts of the world sending money home.

Liberia, 1980s and 1990s

From 1980 to 1997, the West African nation of Liberia, the continent's oldest republic, endured huge economic problems - 17 years of negative growth, according to the World Bank. But like in Tajikistan, the figures are estimates.

A military coup in 1980 led by Sergeant Samuel Doe sparked a period of instability and civil war.

There were internal and external reasons for the economic collapse, says Ian Taylor, professor of international relations at the University of St Andrews and an expert on African economies.

"Internally, gross financial mismanagement was serious. The elite were already corrupt and irresponsible, but this accelerated after the Doe coup.

"Deficits created throughout the 1970s got worse by Doe's excessive military spending to solidify his power base."

Backed by the USA because of his "anti-communism", Doe spent extravagantly and siphoned off taxes directly into his own bank account, says Prof Taylor.

"Externally, the collapse in world steel production in the early 1980s led to a huge decline in the demand for iron ore on the world market, which very seriously affected Liberia's exports."

Other lengthy downturns

Many economists regard a recession as the "persistent deviation" from full employment and growth, says Professor Ritschl. A typical advanced economy should grow 1.8 - 1.9% a year, so growth of only 1%, for instance, over a long time, should be regarded as a recession.

Britain in the 1920s and 30sis a classic example of this kind of slump, he says, starting with a contraction in 1920-21 but never really recovering to normal levels of growth and employment until World War II.

Switzerland has been enduring very slow growth since the 1990s but its problems have been masked by full employment, says the professor.

"The ones we should be worrying about now areSpainandItalybecause productivity growth has stalled since before 2000.

"The global financial crisis didn't come out of the blue. It's true that the mortgage-backed securities crisis was in America but the reason the crisis hit Europe so hard was the structural weaknesses."

And further back...

Prior to globalisation and the Industrial Revolution, recessions were more severe than now, says Professor Ritschl, because they were more difficult to ride out and often sparked by catastrophic events which killed millions.

"TheIrish Famine[in the 1840s] was pretty devastating and had very long-term effects. First and foremost it reduced Ireland's population and I'm not sure it ever really recovered from that."

TheBlack Deathin the 1340s reduced the world population by a third and it took centuries to recover.

"Historians are still debating how long it took for population levels to recover."

Then there was thedecline of the Roman Empire. Speculation remains about why this happened, says the professor, but one theory is that a major epidemic reduced population density and made it vulnerable to attack.