How much Christianity is hidden in British society?

- Published

As Lent starts, the debate over secularism v cultural Christianity is raging. But just how much of British culture is inspired by religion, asks Stephen Tomkins.

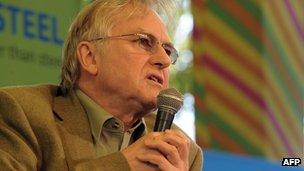

"On the Origin of Species, uh, with… oh God," as Richard Dawkins said last week on BBC Radio Four's Today programme when challenged by the Rev Giles Fraser to give the full title of Charles Darwin's famous book.

That the unofficial pope of Western atheism should expostulate about God in moments when life is a struggle does not of course mean that deep down atheists believe in God after all. But it does illustrate how deeply ingrained religion is in the UK's culture.

Britain is in many ways a secular state, and traditional beliefs and practices have collapsed, but perhaps the UK's national culture is still more religious than we often notice. Trying to take all the religion out of it would be not so much like taking the raisins out of a fruitcake as like taking the chocolate out of a chocolate cake.

So here are some of the places in British society where Christian heritage can easily be uncovered.

Calendar

The academic year revolves around Christmas and Easter holidays, while in the more traditional universities the terms are religious too.

Oxford, for example has Michaelmas, Hilary and Trinity, marking the feast days of the Archangel Michael, St Hilary of Poitiers and the metaphysical constitution of God. St Andrews University has two semesters, Martinmas and Candlemas. Durham has Michaelmas, Epiphany and Easter.

In fact, most annual celebrations are religious in their origins, though less obvious about it.

Valentine's Day is named after a saint

Valentine's Day is a saint's day. Pancake Day, or Shrove Tuesday to the traditionalists, is a last hurrah before the austerity of a pancake-free Lent. Halloween is a last hurrah of the powers of evil before their routine drubbing on All Hallows' Day.

Bonfire Night marks the burning in effigy of the Catholic threat to national security. Mother's Day marks the halfway point of Lent, and one theory of its origin is that it was marked by visiting the region's "mother church" or cathedral.

New Year's Day has no very religious origin, and so can be celebrated by the most zealous secularist - but perhaps not with new year resolutions, which are a Puritan tradition of spiritual improvement.

The shape of our week is religious - the seven-day cycle with a day of rest being one of Judaism's contributions to our society. Days and months are named after (pagan) gods, while our years are numbered after the birth of Christ. The very notion of holidays perpetuates the age-old observation of "holy days".

And the fact that the financial year obstinately holds off until April marks the fact that Christ was born on 25 December, and therefore conceived on 25 March, the Feast of the Annunciation. This was New Year's Day until the 18th Century, and the tax year got separated from it when we jumped 11 days switching to the Gregorian calendar in 1752.

Language

Our language is thick with God and matters arising. Most swearwords, along with milder exclamations, if they are not related to bodily functions or organs, are religious.

Many are explicit: OMG, for Christ's sake, what the hell, good heavens, damn. Others are under cover: "Heck" is hell, "Dickens" is the devil, "goodness" is God, "blimey" is "God blind me", "strewth" is God's truth.

Richard Dawkins' surname ultimately derives from King David

The linguist David Crystal found 257 phrases in everyday English that come from the King James Bible. Whether you "give up the ghost" or "go from strength to strength" you're reciting scripture - and if you complain that I'm putting words in your mouth, you're doing it again. It's just a cross you'll have to bear.

Other phrases are not Biblical but obviously religious if you listen to what you're saying - singing from the same hymnsheet, preaching to the converted, pop idol, godsend, making a sacrifice, hell to pay.

Traditional British Christian names - well, the clue's in the name, isn't it? Of the notable atheists dubbed the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Sam Harris and Daniel C Dennett have Biblical first names, and Christopher Hitchens was named after a saint. Only Richard Dawkins has a secular given name, but atones for it by his surname, which is ultimately inherited from King David, the psalmist and giant killer.

Sport

Football may be a religion in itself, with its worship, rituals, vestments and tribalism, but it still has room for Christian traditions. Witness how players cross themselves and point heavenwards, or put their hands together and pray to the referee to avoid being booked or sent off.

Meanwhile, the fans sing hymn tunes - occasionally with the original words such as Abide With Me at cup finals. More often they are adapted, such as "three-nil" to the tune of Amazing Grace, "We are the famous CFC" to the tune of The Lord of the Dance, or "You're not singing any more" to the tune of Bread of Heaven.

Food and drink

There are brands and products that take their name from religious sources, whether for historical reasons or just because it sounds good. So there are Quaker Oats and Cathedral City, Angel Delight, devil's food cake and hot cross buns. There are Saints Ivel, Agur and Austell.

Upholding the traditional connections between holy orders and alcohol are Bishop's Finger, Blue Nun and Abbot Ale. And the biggest fish sales of the year are still on Good Friday.

Folklore

Certain superstitions are supposed to have religious roots. In medieval lore, Satan loved to take the form of a black cat and hated salt, a symbol of purity, hence the unluckiness of seeing the one and the remedy of throwing the other over one's shoulder.

Fear of the number 13 may have stemmed from Judas being the 13th member of the Last Supper. And we still bless people when they sneeze.

National identity

St Andrew's Day is a public holiday in Scotland, as is St Patrick's Day in Ireland, though attempts to do the same for David and George have not so far succeeded. Their crosses mean that British flags commemorate three Christian martyrdoms, while the British national anthem is a prayer that mentions God about as often as humanly possible.

Music

While Masses, oratorios and sacred cantatas have an important place in classical music, the pop charts may not seem a welcoming place for theology.

Alexandra Burke's cover of Hallelujah topped the charts

In fact, in one way or another, religion is a recurrent theme for many of the most respected and/or best-selling music acts. Witness everything from the gospel of Elvis and Mariah Carey to the hymns of Bob Marley and Van Morrison.

Indeed the influence of religion can be found as much in the controversies of Madonna or the Rolling Stones, as it can in the spirituality of artists as diverse as Bob Dylan, Kanye West, Prince and U2.

Even X Factor has had its religion-tinged phase thanks to Leonard Cohen's Hallelujah. And Andrew Lloyd Webber is looking for Jesus in his reality casting show Superstar. He will doubtless find him.

Stephen Tomkins is the author of A Short History of Christianity.