What can political donors learn from history?

- Published

Adelson could probably finance an entire presidential campaign on his own, Forbes Magazine says

A billionaire Las Vegas casino magnate has said he might donate $100m (£64m) to support Republican Newt Gingrich's presidential campaign. He joins history's long list of great - and ignominious - political money men.

Sheldon Adelson, who is worth an estimated $25bn, is almost single-handedly responsible for keeping Mr Gingrich's bid for the Republican nomination afloat, analysts say.

He and his wife have already donated $10m to a nominally independent political fund that has bought adverts for the former House speaker's campaign.

"What scares me is the continuation of the socialist-style economy we've been experiencing for almost four years," Mr Adelson told Forbes Magazine.

"That scares me because the redistribution of wealth is the path to more socialism, and to more of the government controlling people's lives."

Mr Adelson's big contributions place him among a new generation of US political money men freed to donate millions by recent Supreme Court decisions that overturned campaign finance restrictions.

But he is part of a long tradition - stretching back into antiquity - of wealthy men who used their cash to buy political influence.

Here are some lessons he could heed:

Lesson 1: Patronage can yield profits

Crassus, seated, enabled Caesar's rise by backing his debts and funding his campaign for consul

Known to historian Plutarch as "the richest of the Romans", Marcus Crassus got even richer by staking Julius Caesar's military career and his later election as Roman consul.

"We never would have heard of Caesar without Crassus," says Philip Freeman, chairman of the classics department at Luther College in the US state of Iowa and author of a recent biography of Caesar.

Born in a household of relatively modest means, Crassus aligned himself with Roman dictator Sulla and grew rich by taking property Sulla had expropriated from his own political enemies.

He made "the public calamities his greatest source of revenue", Plutarch wrote, and also made lots of money as a contract tax collector.

In 61BC, Caesar was named to a military post in Spain, but his creditors sought to prevent him from leaving Rome.

Crassus guaranteed his debts - to the sum of about $23m (£14.6m) in 2012 figures, by Prof Freeman's calculation.

Two years later, Caesar ran for election as consul, the highest political office in the Roman republic. Crassus funded his campaign, which depended on officially condemned but widespread vote-buying, Freeman says.

In return, Caesar pushed through legislation giving the contract tax collectors a break in the amount of money they had to return to the central government.

"It's like if Mr Gingrich got to be president and passed a bill making casinos tax exempt - for his benefactor back in Las Vegas," says Prof Freeman.

"It was a great financial play for Crassus purely in monetary terms."

Lesson 2: Have an exit strategy

Sir William de la Pole of Hull was a 14th-Century wine importer, wool merchant and financier who lent staggering sums of money to King Edward III to finance his lavish lifestyle and his wars in France and Scotland.

"There's no doubt that Pole did acquire a great deal of wealth, and wealth brought him social status," says Jonathan Sumption, a historian and jurist who has written three volumes about The Hundred Years War.

"His sons went on to become Earls of Suffolk, noblemen, which nobody would have accused William of being. You couldn't do much better than that. This was simply the normal way in which money was converted into status."

Pole's involvement with the crown began in earnest in 1327, when he lent Edward III £2,001 (about £1.4m in today's money, according to Measuringworth.com, a calculator devised by economists at the University of Illinois at Chicago) to hire mercenaries to fight the Scots.

In 1336-1337, Edward III sought to exploit the wool industry to finance the start of the Hundred Years War with France.

Pole organised other wool growers into the Wool Company, in effect purchasing from Edward III the right to export wool on privileged terms, Mr Sumption says.

Between June 1338 and October 1339, he lent the crown £111,000 (more than £86m in 2012 figures).

For Pole himself, the story did not end well.

Edward III grew resentful at his dependence on Pole and imprisoned him for two years. He was released because the king again needed his help raising money.

Edward defaulted on his debts because the wars cost more than his tax revenue, Mr Sumption says, and Pole and his partners went bust.

"Lending to the king was a mug's game," Mr Sumption says. "The problem was that if you didn't you were likely to be ruined anyway."

Lesson 3: The stakes are high

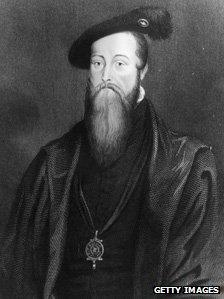

When Seymour's political intrigue failed, he lost more than his shirt

When Edward VI ascended to the throne in 1547 at the age nine, members of the Tudor court began jockeying for position and influence.

Two of the top intriguers were his uncles Edward and Thomas Seymour.

Edward Seymour managed to have himself declared Lord Protector of the Realm, Governor of the King's Person and later Duke of Somerset, making him the most powerful man in the court.

But Thomas Seymour, who had been well placed under Henry VII, found himself increasingly frozen out.

Among his several schemes to gain influence over the boy king, Seymour began supplying him with pocket money, telling him "you are a beggarly king, you have no money to play or to give".

Edward VI, who had reportedly complained to Seymour that Somerset "deals very hardly with me and keeps me so straight that I cannot have money at my will", wanted the cash to pay for musicians in his court and to reward his personal servants, says John Cooper, a lecturer in early modern history at the University of York.

Seymour gave the king £188 (about £70,400 in today's value), funnelled in part through Edward's personal servants and his tutor.

"It's a political gamble that fails very dramatically," Mr Cooper says.

When Somerset found out about that and other intrigues (Seymour also flirted with the teenaged Princess Elizabeth, whom he may have hoped to marry), he had him arrested and charged with treason.

He was beheaded at the Tower of London.

On hearing of his execution, Elizabeth said: "This day died a man with much wit, and very little judgment."

Lesson 4: Be prepared to lose big

Among the liberals incensed about the Vietnam war in the late 1960s and early 1970s was Stewart Mott, the black-sheep son of a wealthy Detroit car manufacturing family.

Mott, who described himself as an "avant-garde philanthropist", donated more than $200,000 to the 1968 presidential campaign of Eugene McCarthy, and about $400,000 in 1972 to George McGovern, the Democratic challenger to President Richard Nixon, according to Mr Corrado, the campaign finance expert.

His big contributions in part led Congress to enact strict limits on direct contributions to political campaigns that remain in effect to this day (though giving to independent committees are unlimited).

"He identified with their politics, and whatever one means by progressive, he was it," says Victor Navasky, professor of journalism at Columbia University.

"He cared about them, and he hoped to help them attain the White House."

Despite Mott's seed money, Mr McGovern suffered one of the greatest political defeats in American history, winning only the state of Massachusetts and Washington DC.

Mott's support for liberal candidates earned him a spot on Nixon's infamous enemies list. Nixon aide Chuck Colson listed him as "nothing but big money for radic-lib candidates".