The last of the glass eye makers

- Published

Glass eye technology was perfected in Germany about 200 years ago

Losing an eye through illness or accident can devastate a person's life. A "glass" eye can help some people come to terms with it, but others choose to wear them for more nuanced reasons, writes Jolyon Jenkins.

In a tiny room in a north London suburb, Jost Haas makes a glass eye.

He holds a glass tube over a bunsen burner, twirling it constantly, blows through the molten glass, and turns it into a sphere.

His patient Dan Light has only one working eye.

Haas uses coloured glass sticks to match the colour of that eye - not just the pattern of the iris, but the red veins of the sclera.

He also has to make the glass eye fit the shape of Dan's bad eye, and there is only one chance to get it right.

A typical modern glass eye is not, as you might think, like a large solid marble. It is a hollow half sphere, a thin shell that fits over the non-working eye, if it is still there. Otherwise it goes over a ball that has been surgically implanted into the eye socket and attached to the eye muscles.

Most prosthetic eyes will have a degree of movement.

Behind each of Haas's customers is a tragic story. Of cancer, of assault, even of a moment's inattention with a bungee cord.

Light, now in his 30s, has been coming to Haas since early childhood

He lost his eye when he was four in an accident caused when he and his brother were fooling around with equipment left lying about by a plumber.

Haas is from Germany, which has always made the finest glass eyes. He came here in the 1960s. But now he is close to retirement, and when he switches off his bunsen burner for good there will be no more glass eye makers in Britain.

Light is taking the opportunity to stock up against that day.

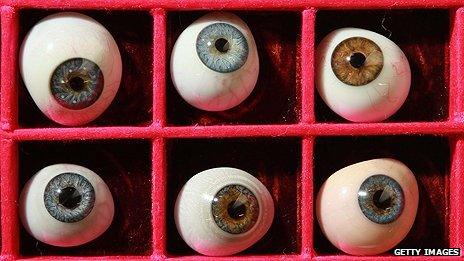

Most modern prosthetic eyes are made from acrylic rather than glass

An artificial eye is not like an artificial leg, or a false tooth. It does not do anything a real eye can do.

Its benefits are purely social and psychological - to make other people feel comfortable and to make the wearer feel normal.

For a while, says Dan, he chose not to wear a prosthetic eye, feeling that the world should accept him as he was. But the glass eye became a battleground between his mother and his girlfriend.

His girlfriend told him that the "bad" eye was beautiful. His mother said that wearing the prosthetic was like wearing deodorant - something you did for the benefit of others. His mother won.

For many people, a face without two identical eyes is disconcerting. Even if it takes only a moment to adjust, for a one-eyed person, life is made of such moments.

We read a great deal into eyes, or their absence.

According to the saying, they are the window to the soul, so is Haas creating an artificial piece of character?

"I might create a piece of character, but if there isn't a soul there I can't change that either, can I?"

Haas gave me one of his eyes - a reject - to take as a souvenir. For days I carried it round and showed it to people. The reactions were extraordinary.

Although they knew it was nothing but a piece of glass, they recoiled from it as if it possessed an evil power.

Haas's eventual retirement may cause difficulties for his long-standing clients, but nowadays most false eyes are made of acrylic not glass.

The pattern is painted on with a fine brush. Unlike a glass eye, an acrylic one can be repolished if the surface loses its shine.

A false eye maker is known as an ocularist, and ocularists are possibly the world's most practical artists.

The senior ocularist at Moorfields Eye hospital, Peter Coggins, went to art college but rebelled against the intellectualised language of conceptual art.

The relationship between ocularist and patient is intimate, he says. "Quite a big part of the job is the first appointment when you see the patient, where things can be emotional - there's a lot of talking and reassuring.

"But you can't promise to make you something that even your own mother won't recognise. It's impossible to do that."

For some people getting the prosthetic eye is liberating and transforming.

Bob Lewis lost an eye to cancer two years ago. The first time he was fitted with his new one was overwhelming.

"I cried," he says. "I was whole again. I would never have vision through it, but I was visually perfect again."

Others struggle with the whole concept of a prosthetic eye.

Vera White, who also had a tumour, had to undergo counselling to reconcile herself with the new eye.

"It's the falseness of it, and the fakeness. I actually wanted my eyelid stitched closed."

In the end she cut a deal with it. "I looked in the mirror and said to it: 'I don't like you. I'll never like you.

"But this is the deal, you can just stay there."

The fact that she found herself talking to a piece of plastic is, in its own way, a tribute to the power of the unseeing eye.