Dingoes: How dangerous are they?

- Published

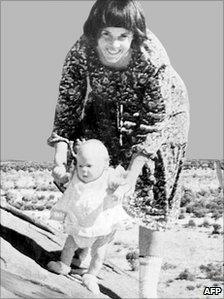

A new inquest is being launched into the death of a baby who disappeared in 1980 from an Australian camping site. Her parents insist she was killed by a dingo, but polls show some Australians are unconvinced. So how dangerous are the animals?

It is the fourth inquest into the world-famous case of nine-week-old Azaria Chamberlain, which has haunted Australia for 31 years, and her parents hope it will be the last.

Lindy Chamberlain was convicted of murdering her daughter in 1982. Michael, her now former husband, was convicted of being an accessory. Both were later cleared after new evidence emerged supporting their story.

The case divided the nation and for a long time made Chamberlain - who now goes by the name of Chamberlain-Creighton - the most hated woman in Australia.

A body has never been found and the official coroner's record still states the cause of death remains "unknown". Officials have reopened the case after receiving fresh information from Azaria's parents. They hope to finally, and definitively, determine how she died.

A lot of crucial evidence hinges on dingoes and their behaviour, so how dangerous are they to humans?

Like any wild animal, a dingo can be very unpredictable. That's the message put out by the Queensland Government as part of its work to educate people to be "dingo safe".

The animals are not "tame or trained", it warns on its website. "Dingoes may be closer than you think and they move quickly," it adds.

It has a keen interest in getting the safety message across. Fraser Island, a World Heritage site, is situated off the southern coast of Queensland and is home to what is regarded as the purest dingo population in Australia.

There are thought to be about 120 of the animals, which are one of the attractions that pull in around 500,000 tourist annually. The island's dingoes are more curious and less wary than mainland dingoes and the authority warns people not to feed them or leave children alone, even for a few minutes. It also advises visitors to walk in groups.

But while no-one disputes that any wild animal can be unpredictable, dingoes are naturally shy and cautious around people. The vast majority will avoid us if given the opportunity, say experts.

"They can be inquisitive, but are very cautious and suspicious of anything new in their territory," says Dr David Jenkins, a dingo expert at the Charles Sturt University in New South Wales.

"I have spent a lot of time in the bush during the last 25 years working with dingoes and doing other things. There have been several occasions when dingoes have spent time watching what I have been doing, but at no time did I feel threatened."

A very small number seem to like the company of humans in short bursts, says Lyn Watson, of the Dingo Discovery and Research Centre in Victoria. She has worked on a day-to-day basis with the animals for the past 25 years.

Azaria's parents were cleared over her death in 1988

When disturbed, their instinct is not to turn aggressive, she says. "Given confrontational conditions, dingoes will choose flight before fight every time."

But like any wild animal they will protect their territory, their mate and their young if put in a seriously threatened position, say the experts.

"If they feel threatened or trapped they can become belligerent and aggressive," says Dr Jenkins. "But it depends very much on the circumstances, particularly if food is involved, and also how their behaviour is perceived by the person involved in the interaction."

A big problem is people's behaviour around dingoes, he adds. They forget they are dealing with wild animals, not pet dogs.

"People can be very complacent with dingoes because people are used to dogs. Dingoes are closer to wolves than dogs. If people feed dingoes or there are food scraps commonly available in an area, such as around garbage dumps, dingoes then can become very bold and that is usually when there are incidents involving people."

The Queensland Government says visitors sometimes feed dingoes to get close to them for good photographs, or leave leftover food around their camps which attract them.

But incidents of dingoes attacking people are still statistically very low, experts argue, while acknowledging that any attack is one attack too many.

"In our entire documented Australian history only a handful of cases of human/dingo conflict where humans were injured, or which resulted in death, have been recorded," says Watson. Compare this with hospitalisations and a considerable death toll annually from domestic dogs, she adds.

The Australian Companion Animal Council (ACAC) estimates the nation's public hospitals treat an estimated 12,000 and 14,000 people for domestic dog bite injuries.

New figures on dingo attacks on Fraser Island have been collated by the Queensland Government's Department of Environment and Resource Management (DERM). They will reportedly be provided as evidence at the Azaria Chamberlain inquest.

They show 98 "dangerous dingo attacks" have been recorded since 2002. There were two high-profile attacks before 2002, including a mauling that resulted in the death of nine-year-old Clinton Gage in 2001. In 1997, a five-year-old boy was also badly attacked by two dingoes.

The information was made available through Freedom of Information requests paid for by Save Fraser Island Dingoes Inc. Jennifer Parkhurst, vice-president of the organisation, disputes the classification of the figures. She says in many cases incidents recorded as "dangerous attacks" were dingoes "loitering" or merely making contact or coming close to the person.

"In only three instances did a bite take place and only one of those required hospitalisation," she says.

High-profile attacks have resulted in dingo culls, so accurate recording of incidents is a big issue.

With few pure dingoes left, another issue is their hybridisation with dogs. Some argue that where the dog gene is dominant it can make dingoes more aggressive - though others say there is no scientifically reliable research on the subject. Dr Jenkins say we simply do not know at this moment in time.

Dingoes are seen as pests by the sheep industry because of their attacks on livestock, and measures to control them are used. But they also play an important role in Australia's ecosystems, keeping fox and feral cat numbers in check.

Friend or foe, thanks to the baby Azaria inquest, dingoes are likely to be making headlines again.