BBC World Service at 80: A lifetime of shortwave

- Published

The BBC World Service - which marks its 80th birthday on Wednesday - was broadcast only on shortwave back in 1932. Today, audiences on FM, digital radio and the internet are growing fast while shortwave is in decline, but for millions it remains a lifeline.

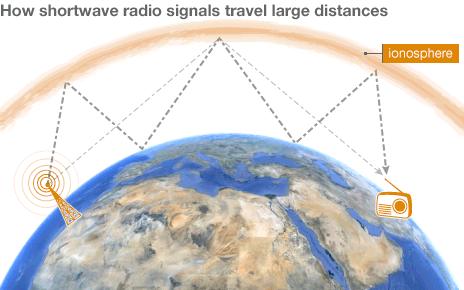

Shortwave listeners catch a signal that travels thousands of miles across international boundaries, sometimes eluding censors, by bouncing off the turbulent gases of the ionosphere, the layers of electrified gas several hundred kilometres above the earth.

It's a signal that can be capricious - subject to interference from electrical storms and other atmospheric disturbances and, mysteriously, often best at sunrise or sunset.

But even when heard against a background of electronic warbling, whistling and hissing, shortwave has reliably delivered the news for 80 years. Four listeners tell their stories.

Robert Mulvaney, glaciologist, Antarctic

I am a glaciologist studying climate change who works "in the field" in Antarctica. This means living in a tent for up to 80 days at a time.

In the past, I used to cut out the daily World Service programme schedules for one week from the newspaper in the UK, and stick them into the back of my diary, then use this as a guide. Generally I would listen in the evenings after we had finished work for the day.

We live, sleep and cook in pyramid tents, two people in each tent. My routine was often to sit in the tent cooking on the Primus paraffin stove, and listening to the BBC World Service with headphones on, occasionally removing them to talk to my colleague.

The best time for listening was when I would get in my sleeping bag (for warmth) and listen to the radio until it was time to sleep.

In some seasons, we have periods when the weather is too bad to work outside - we call this a "lie-up" - and you may be confined to the tent for a few days. Then I would try to listen to the BBC World Service during the day, but the reception was never quite as good as in the evening - I guess it is the structure of the ionosphere, with a more perfect radio reflector during the evening.

When it's not good, I get the range of interferences from slight hissing to the reception strength varying within minutes from strong to weak to strong again. Occasionally we used to get a woodpecker sound overlain on the radio signal - a rapid rhythmic tapping that starts loud and fades.

I always used an extension aerial. Generally, I lay out a long-wire aerial for my Sony radio, which has an extension aerial socket.

The way we do this with the pyramid tents for both the communications radio and my Sony is feed a wire out through the ventilation "dongle" in the apex of the tent, and keep the wire clear of the ground by suspending between bamboo poles.

U Sandawbatha, Monk in Rangoon, Burma

The BBC has been an integral part of my life for over two decades now - I believe I haven't missed a single transmission in all those years. I even kept a diary of all broadcasts from 1988 to 2003, recording all new staff who joined in those years and their first ever broadcast.

I started listening to the BBC Burmese Service in 1988 when the whole country rose up against one-party rule.

I was living in western Burma's Rakhine State, teaching Buddhist scripture to the student monks. I was fascinated by the BBC's coverage of the news and was much impressed that the news I heard on BBC turned out to be exactly what was happening in the country.

I was a well-informed and knowledgeable monk, partly because of the BBC. The BBC, because of its reporting on Burma, was much hated by the military authorities and people had to secretly listen to it within their own homes. But luckily for me, I had my own monastery then and could listen to the broadcasts relatively undisturbed.

Then I left for India for further studies but continued to listen. On my return to Burma, I moved to Rangoon, the then capital and stayed at a monastery on the suburbs of the city. Rangoon was a hotbed of activism against military rule and the military government openly practised a "divide and rule" policy. People were suspicious of each other and that distrust spread to the monasteries as well.

The other monks in the monastery disapproved of my listening to the BBC, because they feared government reprisals, and some even said I was an "informer" providing information to foreign broadcasters. They dubbed me a "reporter monk".

I took more precautions but never stopped listening. I would take my transistor radio and go outside to the farthest corner of the monastery compound, away from other monks, at the times of the broadcasts.

Every day I learned something from the radio. My morning teaching lessons start only after the BBC morning programme and I do my nightly prayer after the evening programme.

My radio is set at the frequencies on which the BBC Burmese broadcasts and I usually tune in a few minutes before the programme starts. I don't want to miss anything. When the weather is bad, it takes more dedicated effort to tune into the shortwave signal, but I don't mind that.

Some people frown on monks listening to the BBC. But I believe my life is enriched by it. The BBC has become a very important part of my life and I will continue listening to it until the end of my life. As Buddha has taught, we living beings must face the truth and bring about the truth. I believe the BBC is earning this merit every day by sharing the truth with millions of listeners.

Gary Rawnsley, Professor of International Communications, Leeds

I started to listen to the BBC World Service in 1984. My father was a long distance truck driver, and would regularly get up at 03:00 and 04:00 to start work.

During school holidays, I would go with him. I distinctly remember listening to the BBC World Service on FM at about 04:00 and hearing the news about Indira Gandhi's assassination. Driving through the dark in my dad's truck, the only people on the road, it seemed like I was the first in the UK to hear this news.

In 1986 my parents bought me a Vega Selena 215 Russian shortwave receiver. It was advertised in a Sunday magazine.

My free time was then spent listening to shortwave radio broadcasts from all over the world. I listened at night because that was the time to hear the clearest signals from as far away as possible. Now I look back and can still sense that feeling of lying in bed, in the dark, straining to hear through the noise. There was nothing more exciting than hearing "This is London" and then the comforting strains of Lilliburllero.

Yes, the shortwave signal was usually rubbish, but part of the charm, the excitement was trying to hear through the noise, the cackle. Chasing stations and frequencies and getting frustrated that yet again, the station I heard was Radio Moscow.

For my 18th birthday my parents bought me a digital radio, which meant I had presets and could directly tune to frequencies after reading the World Radio and TV Handbook or Shortwave Radio Magazine. The charm began to wane and is started to become too easy; the romanticism was starting to wear off.

Even then I considered the political ramifications of my hobby and published a couple of articles in Shortwave Magazine. Once I got to University to study comparative and international politics, the shortwave radio was my personal tutor about world events.

When I began to travel - first to Taiwan with my future wife as a tourist and then to Washington for PhD fieldwork - I bought a small portable shortwave receiver. The only station I listened to was BBC World Service to hear what was going on in the world and at keep in touch with home.

I love the idea that shortwave radio can be a catalyst for international events; that it can help "nation speak peace unto nation"; be an instrument of diplomacy (and now the fashionable concept of soft power); and bring music, drama, news and opinion to millions around the world.

It fed my appetite for travel and I have managed to visit many of the countries that I used to hear announced in the dark small hours of my teenage years. My passion for understanding international relations and demonstrating that there is an undeniable connection between International Relations and International Communications remains the driving force in my academic work.

There is still something romantic about the fact that someone is speaking into a microphone in London and someone else is listening to it in Kampala, Kuala Lumpur or Kentucky.

Hassan Nur, Jowhar, Somalia

I am based in the town of Jowhar, 90km north of Mogadishu [an area currently controlled by al-Qaeda affiliate Al-Shabab].

I listen to the BBC World Service in English and the BBC Somali Service every day, morning and evening.

It is very difficult to get reception in the morning - it is very limited. But in the evening it is OK, it's quite clear. I listen on my bed. I have quite a big radio and I have to have the aerial extended to pick up the broadcasts.

I have to listen every day - for me it is compulsory to tune in.

I am 36 years old and I have been listening for about 15 years. Why do I like listening to the BBC on shortwave? It provides breaking news. It describes the political turmoil and what is happening with insurgents - in Africa and around the world. The BBC helps societies to be updated, wherever they are.

Research by Bethan Jinkinson