Texas execution: How much is a death worth?

- Published

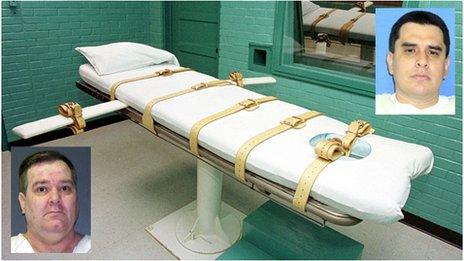

George Rivas, top right, was executed last week in the Texas death chamber in Huntsville; Keith Thurmond is to be executed on Wednesday night

The cost of lethal injection drugs used in the US to kill criminals on death row has risen dramatically over the past year. The increase comes as their manufacturers move to prevent them being used in executions.

The state of Texas is scheduled to spend $1,286.86 (£811) to kill Keith Thurmond on Wednesday night.

Thurmond, a 52-year-old former air-conditioning technician, was convicted in 2002 of killing his estranged wife and her lover in an argument over child custody.

A little after 18:00 local time (midnight GMT), Texas prison officials will strap Thurmond to a gurney and inject a series of three drugs into his arm.

The cost of the death drugs has risen 15-fold since 2010, when they cost the state $86 (£55).

That is because the drug formerly used to sedate the patient, thiopental sodium, is no longer available, having been pulled off the market in 2010.

As a result, Texas and several other states switched to another sedative, pentobarbital. The drug is significantly more expensive - and it may soon become impossible for capital punishment prisons to purchase.

"Even though it is a small amount in the big scheme of things, it represents one more spiralling expense that makes the death penalty less reliable and more costly," says Richard Dieter, executive director of the Death Penalty Information Center in Washington DC.

Rivas, shown here in 2001, was sentenced to die for killing a man after a prison escape

"From a cost-benefit analysis, the scales tip away from keeping capital punishment."

Volumes of research have suggested the death penalty is significantly more expensive to taxpayers than the punishment of life in prison, due largely to the lengthy legal processes involved.

Fundamentally, it stems from the use of what opponents say is a barbaric, antiquated mode of punishment within a sophisticated legal system ostensibly aimed at ensuring the rights of the accused, preventing punishment of the innocent, and executing human beings without causing them too much physical pain and suffering.

Aside from Texas, most of the 34 US states with death penalty laws on the books seldom carry out executions. But even those that do must spend billions of dollars to defend the death sentence against prisoners' appeals and to house the condemned securely and what they see as humanely.

California, for instance, has spent about $4bn (£2.54bn) since 1978 to fund its capital punishment system, but has executed only 13 prisoners, Federal Judge Arthur Alarcon and Loyola Law School Professor Paula Mitchell foundin a law review article, external.

In that same period, at least 78 death row inmates died of natural causes, suicide or other causes while awaiting execution, they wrote.

In Washington state, one prosecutor told a committee of the state bar association that capital cases are at least four times as costly to prosecute as a non-capital murder trial.

"The rarefied nature of a death penalty case results in more motions being brought and more advocacy being presented, which further adds to the time and costs of a capital case," the commission reported in 2006.

The on-the-day costs of the execution vary from state to state, but are relatively small compared to the costs the states incur on the way to the death chamber.

The state of Washington spent $97,814 (£62,004) to execute Cal Brown in 2010.

Most of that was staff pay, but the state also had to hire fencing and lighting for the demonstration outside the prison, a tent for news media, food for the special security teams, and counselling for staff, says Maria Peterson, a spokeswoman for the Washington department of corrections.

Also, the thiopental sodium used to sedate the convicted murderer cost $861.60 (£546), she says.

Ronnie Lee Gardner's 2010 execution by firing squad cost Utah $165,000 (£105,000). Most of that was staff pay, but $25,000 (£15,800) went on materials used in the execution, including the chair to which he was strapped and the jumpsuit he wore, a corrections spokesmantold the Salt Lake Tribune, external.

Washington state paid for counselling for staff after Cal Brown's execution

The execution of rapist and murderer Robert Coe in 2000 cost Tennessee $11,668 (£7,395), according to areport by the state comptroller, external. That included medical supplies and personnel and the death drugs.

The cost of the death drugs in Texas, Ohio, Oklahoma and other states has risen as manufacturers pull the drugs off the market, not wanting to supply pharmaceutical products used to end lives.

Texas and other states switched the sedative used to render the condemned person unconscious from thiopental sodium to pentobarbital last year after the only US maker of the drug, Hospira, said it was pulling the drug off the market in order to avoid a row with authorities in Italy, where the drug was manufactured.

In December, the European Commission ordered EU firms wanting to export drugs that can be used in lethal injections to ensure the product was not going to be used for executions.

Indian producer Kayem Pharmaceuticals has also said it will no longer sell thiopental sodium to US prisons.

It is unclear how long pentobarbital, the current replacement drug, will be available.

The only company approved by US drug regulators to market the sedative in the US, Danish pharmaceutical giant Lundbeck, has just sold the drug to Illinois company Akorn, which has pledged to restrict distribution of it to prevent it being sent to prisons in capital punishment states.

Now, purchasers must sign a form affirming they will use the drug, normally used to treat epilepsy and other conditions, on their own patients and not resell it without authorisation.

The difficulty obtaining the death drugs illustrates the problems inherent in lethal injection as an execution method, says Kent Scheiddeger, legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, which supports the death penalty.

"It amounts to medicalising a procedure that shouldn't have anything to do with medicine," he says.

"It's supposed to be punishment - it shouldn't be this quasi-medical procedure. It just strikes me as wrong and now we have all these additional complications. Manufacturers, particularly in Europe, try to meddle in things that are none of their business and try to cut off the supply."

Mr Scheidegger does not foresee a halt to executions forced by a lack of drugs, as the executioners can merely change the ingredients in the cocktail, he says.

"Any barbiturate will do it," he says.