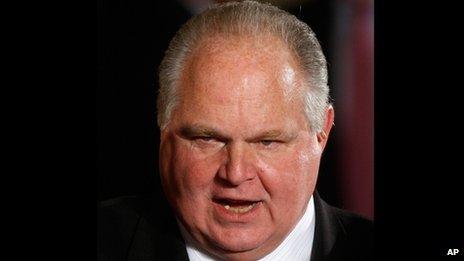

Can Limbaugh survive advertiser boycott?

- Published

Rush Limbaugh's apologies to a student he called a "slut" have not stopped advertisers deserting his top-rated talk radio show. Can he survive the controversy?

Rush Limbaugh has made a career out of controversy - and has seen off boycotts before.

In 1994, Gay and Lesbian Americans and the National Organization for Women boycotted orange juice after the Florida Citrus Commission hired the veteran right-wing radio host as a spokesman.

Protesters furious at what they saw as the misogynist and homophobic nature of his programme urged consumers to "Flush Rush. Drink prune juice".

Contraception

But they were met with counter-protests by Limbaugh fans who cleared the shelves of orange juice in organised "buycotts".

Limbaugh's latest controversy may not be shrugged off so easily.

But could it really spell the end for America's highest-rated talk radio show?

The row began last week when Limbaugh attacked Georgetown University law student Sandra Fluke, after she advocated healthcare coverage for contraception at a hearing on Capitol Hill.

Limbaugh suggested Ms Fluke wanted taxpayers to pay for her to have sex, telling listeners: "What does that make her? It makes her a slut, right? It makes her a prostitute."

His comments were denounced by Republican presidential contenders, although they chose their words carefully - Limbaugh has millions of loyal listeners and is a powerful voice among grassroots Republicans.

President Barack Obama telephoned Ms Fluke on Friday to offer his support.

By this time, a social media campaign had taken off around the Twitter hashtag #BoycottRush, with a string of companies heeding the call to pull ads from the show.

'Racist'

One advertiser, internet florist ProFlowers, said: "Mr Limbaugh's recent comments went beyond political discourse to a personal attack and do not reflect our values as a company".

By Saturday, with the boycott gathering pace, Limbaugh issued a written apology, saying his "choice of words was not the best, and in the attempt to be humorous, I created a national stir, adding: "I sincerely apologize to Ms Fluke for the insulting word choices."

But if the intention was to stem the flow of advertisers heading for the exits, it did not work.

On Monday, Tax Resolution and AOL, parent company of news website The Huffington Post, became the eighth and ninth companies to add their names to the boycott.

And a radio station in Hawaii, KPUA-AM 670, became the first to pull Limbaugh's show from its schedules.

Limbaugh repeated his apology to Ms Fluke on his Monday show but also accused her of trying to "force a religious institution to abandon its principles to meet hers".

And in a swipe at his critics, he said: "I acted too much like the leftists who despise me. I descended to their level, using names and exaggerations. It's what we've come to expect from them, but it's way beneath me."

Ms Fluke rejected his latest apology.

Some commentators see parallels with the social media-led boycott against Fox News host Glenn Beck, after he called President Obama "racist", or the Twitter campaign over phone hacking that preceded the closure of a British tabloid, The News of the World.

'Liberal elites'

Simon Dumenco, media correspondent and columnist for Advertising Age, says: "There is definitely a parallel there. I think it's quite possible that this kind of thing, even five or six years ago, pre-Facebook and Twitter, would have died down quicker.

"Because he [Limbaugh] might not have seen this groundswell of outrage. He is used to taking his hits from the so-called liberal elites. Limbaugh getting criticism from everybody in the media, with the possible exception of Fox News, is par for the course.

"But the fact that there was this social media uprising and direct messaging to his advertisers I think tipped the scale in terms of him deciding to make one of his rare apologies. Social media has extended the momentum of the story."

But other commentators are more sceptical about the power of social media, and question whether a self-selecting online "mob," of the kind assembled on Twitter and Facebook, can be a true expression of public opinion.

'All American Muslim'

In the case of Glenn Beck, they argue, it was falling ratings rather than advertising dollars, which were simply re-allocated to other parts of Fox's output, that led to his departure in 2011.

With the News of the World, the advertiser boycott played a part, but we may never know whether it was the killer blow to the world's biggest-selling English language newspaper.

Some, such as Mr Dumenco, believe it was seen as expendable by News Corporation's US board.

Companies can also suspend ads with great fanfare, when they see their rivals doing so, only to return later when the fuss has died down. Or they can simply re-allocate their cash to different parts of a media empire.

When US retailer Lowe's announced last year it was pulling ad money from "All-American Muslim" - after a campaign by a conservative pressure group - it was seen as the death knell for the show.

But it continued to pour money into the show's channel TLC and other cable outlets owned by Discovery Communications.

Nevertheless, says Brian Stelter, media correspondent for the New York Times, a co-ordinated social media campaign can make life very uncomfortable for companies, many of whom spend millions on managing their online reputations.

"CEOs of companies have seen their competitors ganged up on by the public. Maybe those companies deserved to be ganged up on, or maybe they didn't. Other companies have watched that behaviour with some concern, with some dread.

"Companies are learning how to listen to consumers and react without overreacting."

Free expression

It is no surprise that Limbaugh has become the target of a campaign, he argues, given how many people he has upset over the years.

"There is a wide swathe of people who have had longstanding concerns about Rush Limbaugh, who are acting on these concerns now."

Clear Channel, which syndicates Limbaugh's show to radio stations across America, is standing by Limbaugh's right to free expression.

But whether he remains on air will come down to hard economics.

"Advertisers are weighing how many complaints they receive and they are weighing that against the audience they reach on Rush Limbaugh's show," says Mr Stelter, adding that no-one knows how many national advertisers the show has.

But in common with most commentators, he thinks Limbaugh will survive: "There's no evidence it's a mortal blow, but it's uncomfortable."

- Published6 March 2012