The slow death of prohibition

- Published

The town of Williamsburg, Kentucky, is divided over a vote on whether to bring alcohol into the community

In some parts of the United States prohibition never ended - but how much longer can the remaining "dry" counties stay alcohol-free?

It was known as the noble experiment.

A law prohibiting the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages had been the dream of temperance campaigners in the United States since the early 19th Century.

When prohibition came into force, in 1920, saloons across the country were boarded up and the streets foamed with beer as joyful campaigners smashed kegs and poured bottles down the drain.

But far from ending corruption and vice, as opponents of the "demon rum" had hoped, prohibition led to an unprecedented explosion in criminality and drunkenness.

Thousands of speakeasies selling illegal liquor, often far stronger than legal varieties, sprang up across the country - and gangsters such as Al Capone fought bloody turf wars over the control of newly created bootlegging empires.

National prohibition was finally repealed in 1933, but it never quite died out.

When alcohol regulation was handed back to individual states, many local communities voted to keep the restrictions in place, particularly in the southern Bible Belt.

Today there are still more than 200 "dry" counties in the United States, and many more where cities and towns within dry areas have voted to allow alcohol sales, making them "moist" or partially dry.

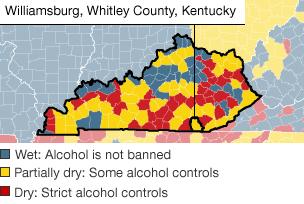

The result is a patchwork of dry, wet and moist counties stretching across the south.

A snapshot of wet and dry America

Every few weeks, somewhere in the US, citizens of a dry area gather enough signatures on a petition to trigger a wet/dry referendum. It is not a one-way street - some communities have voted to remain dry or even introduce further restrictions on alcohol sales.

But hard economic times have accelerated the march of alcohol, and in recent years many communities that have been dry for decades are opting to end prohibition, for fear of losing business to their wet neighbours.

Williamsburg, in the south-east corner of Kentucky, is the latest community to take the plunge.

On Tuesday, it voted by a margin of just 14 votes to allow the sale of alcoholic drinks in restaurants seating more than 100 - moving it from completely dry to partially dry or "moist".

Paul Croley, a local lawyer who led the Yes campaign, which gained 533 votes to the No campaign's 519, claims it is a victory for the forces of progress.

"I hope that we can move into the 21st Century and take advantage of a lot of the things that other communities have.

"It is time to wake up and realise that our standard of living can be as good as our neighbours."

In a similar vote five years ago, the dry campaign won by 130 votes.

It is certainly a big step for this close-knit, deeply conservative community of just over 4,000 citizens on the edge of the Appalachian mountains.

The town has been dry for as long as anyone can remember - apart from a few giddy years following the repeal of national prohibition - and the local Baptist churches fought hard to keep it that way.

Everywhere you looked on Main Street, in the days leading up to Tuesday's referendum, there were signs in shop windows urging citizens to vote no to alcohol sales.

In a roadside tableau outside a Christian mission, a dummy of a homeless man, his disembodied legs sticking out of a tent next to an empty beer bottle, reminded passing motorists of the damage booze can do. "Homeless vote no beer - get saved" read a cardboard sign.

The link between alcohol and urban decay is a common theme. In the nearby town of London, dry campaigners produced a controversial television ad contrasting their pristine, family-friendly streets with shots of graffiti-defaced buildings and abandoned shopping trolleys.

The local TV station refused to air the ad, saying it showed wet cities Jellico and Cumberland in a bad light, but London still voted earlier this month to keep its ban on packaged alcohol sales.

There are no drive-through beer joints or neon-lit roadhouses in Williamsburg, unlike its wet neighbours, but the vacant premises on Main Street and the forlorn, half-empty mall on the edge of town, speak of a community in need of an economic boost.

The dry campaign tried to make a virtue of the town's sleepy, "down home" atmosphere, running newspaper ads which said: "Don't trade your birthright for a mess of potage, or for the dream of fancy restaurants, phantom jobs or ill-defined progress."

Another ad simply said: "Serve Jesus, not alcohol."

Paul Croley, and the group of local business people he represents, argues that allowing alcohol sales would attract new restaurants to the area, creating up to 100 new jobs, and attract more tourists to the town.

In neighbouring towns, such as Corbin, a vote to allow sales in restaurants was the first step towards going fully wet, and new businesses are planning to open there.

Church groups went to great lengths to warn about the dangers of alcohol

But dry campaigners argue that the whole area is in need of jobs and investment and more freely available booze is not the answer.

"If it takes a town of drunks and people that drink to be prosperous, we are going in the wrong direction," said Williamsburg schoolteacher Matthew Ratliffe.

"We want to be prosperous, certainly, but we don't think alcohol is the way to do that."

Like many of his fellow dry campaigners, Ratliffe has experience of alcoholism in his family but he also believes the Church has a duty to protect the morals of the local community.

"I do have a moral obligation as a follower of Jesus Christ to be against alcohol," said the 32-year-old former police officer.

"However, from the experiences I have had in my life I know the downfalls of alcohol and I have seen them personally, through the broken homes and deaths I have seen."

One thing both sides can agree on is that the real problem facing south-east Kentucky is not drinking but drugs.

Methamphetamine and prescription pills like Oxycontin, dubbed "hillbilly heroin", have taken over from bootlegging and the distillation of moonshine as the main source of profit for local criminals.

Bootleggers once "ran wild" in the area, according to Paul Croley, but with the growing availability of legal alcohol in wet towns, any profit to made from smuggling booze across county lines has largely evaporated.

Paul Croley claims Williamsburg will get an economic boost from alcohol sales

Local law enforcement largely turns a blind eye to bootleggers now, and few cases make it to court.

"It is simply somebody driving up the interstate, bringing beer down here and selling it to people. That's it. It's not the Dukes of Hazzard," says Croley.

But the churches argue that alcohol is a "gateway" drug, and is still offered for sale by bootleggers alongside more dangerous substances.

"Bootlegging and drug issues go hand in hand," says Pastor Leonard Lester, who recently fought a successful campaign to keep alcohol sales out of nearby Barbourville.

He even argues that prohibition could boost the local economy because many firms are struggling to find drug and alcohol-free workers.

But for many residents, restricting the sale of alcohol in Williamsburg will not stop people from binge drinking or cut drink-driving deaths, as the churches claim.

It is too easy to cross the state line into Tennessee, just 15 miles away, and stock up on booze.

Resident Robert Miller, a truck driver, said: "You're always going to have drunk drivers. There are some people who just don't know when. But you have responsible folks too, and you can't punish everybody for what the few does. You just can't do it."

The majority of Kentucky's 120 counties are still dry or partially dry, despite the state being home to some of the world's best-known liquor brands, such as Jim Beam and Maker's Mark bourbon.

"It's a strange kind of split personality in the south," says Prof Joe Coker, of University of Kentucky. "We vote for prohibition even though we continue to consume alcohol."

Prof Coker, author of Liquor in the Land of the Lost Cause: Southern White Evangelicals and the Prohibition Movement, says the idea that consumption of alcohol is sinful is deeply embedded in the southern evangelical mind.

And although the temperance movement was born in the northern states, it was taken up with a vengeance by the south in the wake of the Civil War "to demonstrate the higher morality of the south despite its military defeat".

"A good decade prior to national prohibition most of the south-east had dried itself up," he adds.

Traditional southern evangelism is slowly losing its grip on the "larger southern culture", argues Coker, as it becomes "more globalised and diverse".

But if prohibition is ever to fully die out, it could be down to changes going on within the Baptist churches themselves.

"A lot of younger evangelicals who read the Bible very literally, are nevertheless beginning to question the traditional stance against alcohol. They are beginning to say 'Jesus drank wine and Jesus even made wine so why are we still against moderate consumption of alcohol?'

"Ultimately, I do think the trend is going to be towards relaxing these laws."

Wet/dry map explained: Counties are classified as "partially dry" where wet communities exist within dry counties, or where dry communities exist within wet counties. The exact definition of wet and dry differs between states. Alaska, unlike most other states, does not have counties but over 100 Alaskan communities have alcohol restrictions, external. Hawaii has no dry counties. Map researched and produced by John Walton, Harjit Kaura and Nadzeya Batson. Sources include state governments and the NABCA.