Dollar benchmark: The rise of the $1-a-day statistic

- Published

- comments

It's shocking to learn how many people live on less than $1 day - and regular publication of the figures over the last two decades has helped fuel anti-poverty campaigns. But could the statistic actually have done more harm than good?

In the late 1980s, a group of economists at the World Bank in Washington DC noticed that a number of developing countries drew their poverty lines at an income of about $370 a year.

This reflected the basic amount that a person needed to live. Each country had a different sense of what the essentials were, but the figure of roughly $370 was common to all, so the World Bank team proposed it as a global poverty line.

Some time later one of these economists, Martin Ravallion, was having dinner with his wife and, as they chatted, he had what he described as a kind of "epiphany".

If you divide that $370 by 365 days, you get just over $1. And so the catchy "$1-a-day"' concept was born.

Simple, powerful and shocking.

"We intended to have some impact with it," Martin Ravallion recalls. "Make well-heeled people realise how poor many people in the world are."

But it's a lot more complicated, and controversial, than it at first appears.

For a start, Ravallion and his colleagues at the World Bank were not talking about what you could buy if you took an American dollar to a bank and converted it into Indian rupees or Nigeria naira.

A US dollar does go quite a long way in some developing countries.

Instead, the economists calculated a specially-adjusted dollar using something called Purchasing Power Parity, or PPP.

They looked at the price of hundreds of goods in developing countries. And then with reference to national accounts, household surveys and census data, they calculated how much money you would need in each country to buy a comparable basket of goods that would cost you $1 in the USA.

You were under the global poverty line if you couldn't afford that basket.

It's still a reality of life for 13% of people in China; 47.5% in Sub-Saharan Africa; 36% in South Asia; 14% in East Asia and the Pacific; 6.5% in Latin America and the Caribbean. Almost 1.3bn people in total.

And surprisingly perhaps, people who live on $1 a day do not spend all of it on that basket of food - on staying alive. They typically spend about 40 cents on other things, says Professor Abhijit Banerjee of MIT, external.

The first UN Millennium Development Goal focused on halving the number of people living on $1 a day

"Even though they could actually buy enough calories, the fact is they don't. If you look at the people especially in South Asia who live on $1 a day - huge malnutrition.

"They sacrifice calories to buy some entertainment, some pleasure.

"It's a balance between survivalist behaviour and pleasure-seeking behaviour. I think as human beings we need both."

The $1 figure is also an average.

"Poor families… may earn $10 a day and then nothing for two weeks," says Professor Jonathan Morduch of the Wagner School at New York University.

"One season they may earn a lot, one season they may earn very little."

The World Bank's first report on people living on $1 a day came out in 1993. Regular updates since then have played an important role in focusing attention on the world's poor.

But one major reason the number took off and gained a life of its own, was the adoption as the first UN Millennium Development goal to "halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day".

This high-profile target was agreed by the UN General Assembly and embraced by most of the world's development institutions.

Ten days ago, the World Bank declared the goal had been met early, external.

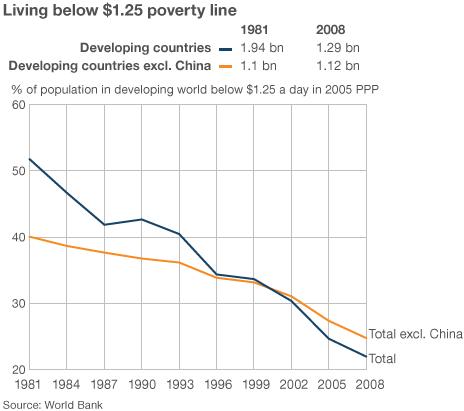

In 1990, 31% of the population of the developing world lived on less than $1 a day - close to 1.4 billion. In 2008, half that proportion did - 14%, or about 800 million.

However, once again, things are more complicated than they may at first appear.

Over the years since the Millennium Development Goal was set, the $1 a day poverty line has been recalibrated. The World Bank's global poverty line measure is now not $1, but $1.25 per day.

When the phrase was first coined in 1993, the purchasing power parity calculations were based on price and consumption data from the 1980s.

But by 2008, the World Bank economists had more and better data on price and consumption, enabling them to refine these calculations - and more developing countries had calculated poverty lines.

So the poverty line was re-set at $1.25, at 2005 PPP calculations. This represented an average of the poverty lines set in 10-to-20 developing countries.

The job of halving the proportion of people whose income is less than $1.25 a day has almost been done, but not quite.

In 1990, 1.9bn people - 43% of the developing world - lived on less than $1.25. In 2008, about 1.3bn, or 22% did.

Despite its success at driving home just how many people are living in extreme poverty, some critics think the $1-a-day benchmark has done more harm than good.

It's a "successful failure", according to Lant Pritchett, an ex-World Bank economist who is now Professor of the Practice of International Development at Harvard University's Kennedy School.

"It's a wildly successful PR device that I think has been a failure in terms of achieving the objectives of improving human well-being in the world," he says.

He argues that it has put a focus on philanthropy more than long-term development - applying a sticking plaster rather than solving the problem.

"Instead of promoting prosperous economies, it's about 'How do we identify and target and get transfers to the few people under this penurious line?' which just isn't the way, historically, anybody has ever eliminated poverty."

And even at $1.25 it is set too low he says - because someone earning $1.25 or $1.50 is still in dire poverty.

Martin Ravallion: The poorest must be the highest priority

Pritchett proposes an additional $10 poverty line be created.

But Ravallion rejects the criticism.

Progress on reducing the numbers living on less than $1.25 a day has mostly occurred thanks to economic growth, he says, rather than handouts.

And while he accepts that people who make it above the $1.25 poverty line remain vulnerable, and that there has been a "bunching up" of people just above the threshold, he says he has always argued that "we should look at multiple poverty lines", not just the $1.25 figure.

"We should look at the whole distribution. That's what I've said from day one," he says. "What I'm also saying is that our highest priority must be the poorest first."

It's is an argument that divides experts in the field.

Professor Banerjee agrees that the $1.25 a day figure plays a useful role, because there is a finite amount of aid that rich countries are prepared to give and it makes sense, he says, for it to be given to the poorest people.

But Professor Morduch says the figure is so low, it has encouraged the idea that people in this minimal income bracket must lead passive, helpless lives, when this is not the case.

In fact, he says, they are keen to save and need tools, such as bank accounts, to help them do so.

"The whole condition of living on $1 a day has much less to do with that average than with the ups and downs. So it's not surprising that households are very actively trying to save," he says.

"They are not living hand to mouth; they are thinking about the future."