Licence to kill: When governments choose to assassinate

- Published

Can state-sponsored assassination work as a strategy? And can it ever be justified? Governments don't admit to it, but Iranian nuclear scientists know it happens - and it's not easy to distinguish assassination from the US policy of "targeted killing".

Seventy years ago, a team of British-trained assassins were preparing to strike. Their target was Reinhard Heydrich, one of the most feared men in the Third Reich, then ruling Czechoslovakia.

Britain's recently formed Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Czechoslovak exile movement based in London both needed to make a mark.

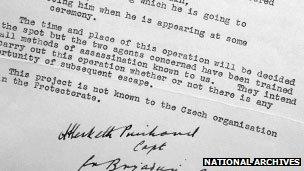

The planning for Operation Anthropoid, as it was known, is detailed in formerly secret memos in the National Archives.

They reveal how two Czechoslovak volunteers trained in Britain and then parachuted in.

Secret memo: "The agents have been trained in all the methods of assassination"

"The two agents concerned have been trained in all methods of assassination known to us," reads one memo from January 1942. "They intend to carry out this operation whether or not there is any opportunity of subsequent escape."

In May of that year, the men ambushed Heydrich's open-topped Mercedes as it cornered a sharp bend.

One man's Sten gun jammed but the other threw a modified bomb sending shrapnel flying.

Heydrich personally tried to chase down the men but the injuries inflicted that day would eventually claim his life.

Nazi reprisals were savage. In the village of Lidice, thought to be linked to the assassins, 173 men over the age of 16 were killed, every woman was sent to a concentration camp, every child dispersed, every building levelled.

This raises a question - is assassination effective?

"It certainly wasn't worth the countless victims that Nazi terror produced over the following weeks," argues Heydrich's biographer, Robert Gerwarth. And Heydrich's successor in Prague was even harsher, he points out.

It is perhaps telling that assassination was not widely employed during the war, after this.

Operation Foxley was typical - the SOE looked at using a sniper to shoot Hitler, and gathered extensive intelligence on the layout of his house at Berchtesgaden. But the plan was cancelled, partly because it was judged unlikely to succeed but also because officials feared it would damage the war effort - they argued that Hitler's replacement might actually be more rational and more effective in fighting Britain.

Concern about the consequences has always been a crucial factor limiting the use of assassination.

But the attractions of assassination as an easy remedy did not go away. During the Suez crisis, Prime Minister Anthony Eden became obsessed with Colonel Nasser, the Egyptian president.

"'I want Nasser, 'and he actually used the word 'murdered','' one minister later remembered Eden saying. MI6 looked at various methods but the opportunity never arose.

The popularity of Ian Fleming's James Bond books in the last 50 years has led many people to believe that Britain's intelligence service really does have a licence to kill. Back in 2009, I asked the then Chief of MI6, Sir John Scarlett, whether there was such a thing.

"We do not have licence to kill," he told me.

I then asked whether MI6 had ever had one. There was a rather telling pause, before he replied: "Well, not to my knowledge."

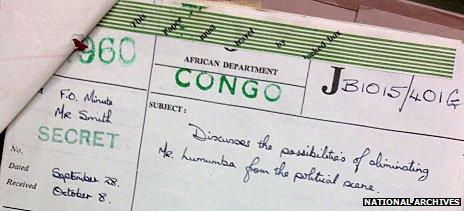

Papers in the British National Archives show that murder was on the minds of some in London during the Cold War.

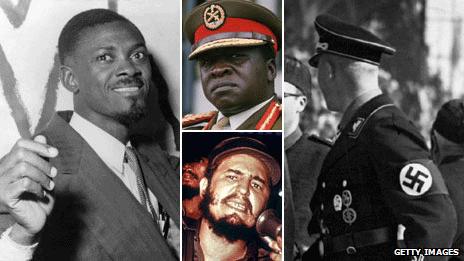

In 1960, Whitehall feared Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba was getting too close to the Soviet Union, so HFT Smith, a British Foreign Office official - and later head of MI5 - outlined two proposals for dealing with him.

The first, which Smith said he preferred, was "the simple one of ensuring Lumumba's removal from the scene by killing him".

He went on: "This should in fact solve the problem, since, so far as we can tell, Lumumba is not a leader of a movement within which there are potential successors of his quality and influence."

Other comments on the file reveal mixed feelings about that option, among British officials.

In Washington, officials took care to avoid President Eisenhower being implicated in assassination even when everyone knew that was what he wanted.

At one National Security council meeting in 1960, the president said he wanted Lumumba "eliminated". There was enough ambiguity in the word to allow for a denial.

The CIA despatched one of their men to the Congo, carrying a tube of poisoned toothpaste, but the local officer threw the tube in the Congo River.

Lumumba was eventually killed with Belgian rather than American or British help. But when this and other plots were exposed in the 1970s - against Fidel Castro in Cuba among others - there was an uproar. President Gerald Ford formally banned assassination.

In Britain, the temptation to employ assassination as a shortcut remained. When he was Foreign Secretary in the late 1970s, David Owen asked his officials if the brutal Ugandan dictator Idi Amin could be killed.

He recalls how the official who acted as liaison with MI6 raised himself up to his full height to tell him: "We don't do that sort of thing."

"Well, we have to consider doing such a thing, the situation is so dire," Lord Owen says he replied.

He argues that the highly personal nature of Amin's savage rule in Uganda meant that killing one person might save many lives.

"It wasn't a regime, it was one person, irrational, out of control. What do you do? I would never call it a moral act," says Lord Owen. "A lesser of two evils, yes."

From the 1970s onwards, Britain was engulfed in controversies over Northern Ireland. There were questions over whether the British authorities had colluded with paramilitaries or operated a "shoot to kill" policy to eliminate members of the IRA.

Terrorism has complicated the issue, blurring the lines between war and peace, combatants and civilians and conflicts between nations themselves.

Israel, which regards itself as in a permanent state of war, has targeted its enemies throughout the Middle East. Its intelligence service, the Mossad, is accused of killing a Palestinian leader in Dubai as well as nuclear scientists in Tehran.

Since 9/11, the US has increasingly talked about "targeted killings" to justify acts which might once have been called assassination.

President Ford's ban on assassinations remains in force though, which helps explain why the US Attorney General Eric Holder was so keen to deny last month that killings carried out by unmanned drones in Pakistan and Yemen - countries with which it is not at war - were "assassinations".

"They are not, and the use of that loaded term is misplaced," he insisted.

Washington even claims that it did not set out to kill Osama Bin Laden in Abbottabad.

The legal justification for "targeted killings" has been provided by broadening the notion of self-defence. It is now taken to mean protecting yourself from imminent attack and, more controversially, targeting any group which is planning an attack, even if you don't know when that might be.

The notion of two armies facing each other on a front line has almost become outdated.

A widely expressed concern is that assassination - or targeted killing - will become more widespread if the legal justifications continue to be stretched.

If America can legitimately kill its citizens in Yemen, why can't Russia do the same in London? A few wonder if it already has, pointing to the poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko.

Christof Heyns, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, fears the worst.

"The spectre that haunts this sort of situation is one of a global war, of a war of all against all," he says. "And that there are no boundaries to where these conflicts can actually be taken and where a specific people can be targeted."

Listen toThe Licence to KillonBBC Radio 4on Saturday, 17 March at 20:00 GMT