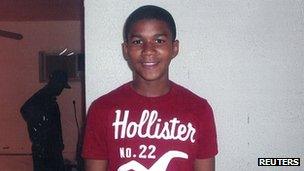

Trayvon Martin: 'Shoot first' law under scrutiny

- Published

Trayvon Martin was returning from a shop with chocolate and tea

The fatal shooting of an unarmed teenager in Florida has prompted protests demanding the arrest of the perpetrator, who says he was acting in self-defence. How much force does the law permit?

On a dark and rainy February night, George Zimmerman sat in his car in Sanford, Florida, a legally-carried 9mm pistol by his side.

There had been a rash of crime in the community, Mr Zimmerman later said, and on that night, the neighbourhood watch volunteer grew wary when a young black man in a hooded sweatshirt appeared.

In a recording of a 911 call released by police, Mr Zimmerman, in his truck, tells a dispatcher that a "real suspicious guy" who "looks like he's up to no good or he's on drugs" was walking through the neighbourhood.

Mr Zimmerman, 28, can be heard huffing and puffing as though he is running, and he tells the dispatcher he is following the person. The dispatcher says: "OK, we don't need you to do that."

Seconds later, a confrontation and a struggle ensued, and a shot was fired. Trayvon Martin, 17, was struck in the chest and died.

Mr Zimmerman was detained and questioned by the local police department, then released without charges. He told police Martin had started the fight and that he shot in self-defence.

Sanford Police Chief Bill Lee has said officers did not charge Mr Zimmerman because no evidence contradicted his account.

But Martin's family have said the Sanford police are protecting Mr Zimmerman because they feel kinship with a man who apparently wanted to be a police officer.

The US Department of Justice has announced an investigation, as requested by the Martin family.

And more than 480,000 people, including film director Spike Lee, actress Mia Farrow and musician Wyclef, have signed a global online petition asking for Mr Zimmerman to be prosecuted.

The incident sheds light on Florida's seven-year-old self-defence law, which critics say is too lenient.

The law, nicknamed a "stand your ground" or "shoot first" statute, gives protection from criminal prosecution or civil liability to people who claim self-defence after a shooting or violent incident.

One of the most expansive such laws in the US, it states that people have no duty to retreat from a place they are legally allowed to be, and have the right to use deadly force if they "reasonably" believe they or another person are threatened with death or serious harm.

Before 2005, deadly force was only allowed if the perpetrator had shown that he or she had tried to avoid confrontation.

George Zimmerman has received death threats

It is difficult to tally how many states have so-called "stand your ground" or "shoot first" laws, because the laws contain nuances in the language.

But according to the Association of Prosecuting Attorneys, at least 33 states have laws that extend the right to use deadly force in self-defence as set out in the "castle doctrine", a principle dating back to British common law that establishes the right to defend the home from invasion and attack.

"If you have a right to be there you should not have to retreat before using deadly force," says Professor Janet Malcolm of the George Mason University School of Law in Virginia.

"The idea is someone is about to assail you. You do not have to turn and flee. You can meet force with force."

Supporters say that in addition to safeguarding the legal rights of innocent people forced to defend themselves in deadly situations, the law also deters crime.

"At some point the people catch on," says Mitch Vilos, a Utah lawyer who has written books on the nation's gun laws. "You don't mess around with somebody who has a gun."

But critics say the laws make it much harder for authorities to prosecute violent crimes, because they establish a presumption of self-defence that is very difficult for authorities to rebut.

"When something does happen, it creates a situation where there is no criminal or civil redress for a person who is injured or who loses a loved one," says Laura Cutilletta, senior staff attorney of the Legal Community Against Violence, a San Francisco group.

"It used to be that the burden was on the person who shot to prove they were in danger and needed to use deadly force. The Florida law shifts the burden: it's the prosecutors' burden to prove a negative."

Under the law in Florida and other states, it appears to make little difference that someone in Trayvon's situation was unarmed.

The laws in Florida and other states with similar laws do not require there be an actual threat, only that the shooter "reasonably believe" he or she is in mortal peril, says Mr Vilos.

"You simply have to show you had a reasonable belief that one of the forcible felonies was about to be committed and you did what you thought was necessary to stop it."

Florida's law goes a step further than others in the US, say some experts.

Supporters of Martin's family demand that the police act

Whereas other states provide for a self-defence argument at trial, Florida's law can make a person who successfully claims self-defence immune from arrest or prosecution.

"That's really extraordinary," says Stuart Green, a law professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey who has studied self-defence laws.

"It's taking the judgement out of the hands of the jury and the prosecutors, and saying to the police, 'you have to make a judgement about whether there should be arrest or not.'

"They're sending a pretty clear message: 'We're not going to regard you even at a preliminary stage as a criminal. You shouldn't be subjected to arrest even though you killed another human being.'"

Criminologist Gary Kleck at Florida State University, who has studied firearms and deterrence, disputes the theory that more lenient self-defence laws deter crime.

"The notion that criminals are sensitive to that kind of change in law is far fetched," he says.

"There are hundreds of new criminal laws passed in each state every year and the average citizen is oblivious to them. I doubt that it has any impact whatsoever."