The Spanish link in cracking the Enigma code

- Published

A pair of rare Enigma machines used in the Spanish Civil War has been given to the head of GCHQ, Britain's communications intelligence agency. The machines - only recently discovered in Spain - fill in a missing chapter in the history of British code-breaking, paving the way for crucial successes in World War II.

A row of senior Spanish military and intelligence officers stand upright in a line in front of a long elegant table in the country's Army Museum in Toledo. In front of them are two modest, slightly battered wooden boxes that are the subject of the day's unusual and high-powered gathering.

Inside they contain a key part of Britain's code-breaking history.

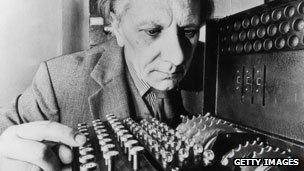

With their lids open, the distinctive black and white keypad and rotors of an Enigma machine used to encrypt communications can be seen.

Enigma machines, developed originally in Germany in the 1920s, were the first electromechanical encryption devices and would eventually carry the country's military communications during World War II. The cracking of that code at Bletchley Park would play a key role in shortening the war and saving countless lives.

The story of how these machines on the table in Spain helped pave the way for Britain's historic wartime achievement is largely unknown.

A non-commissioned officer found the machines almost by chance, only a few years ago, in a secret room at the Spanish Ministry of Defence in Madrid.

"Nobody entered there because it was very secret," says Felix Sanz, the director of Spain's intelligence service.

"And one day somebody said 'Well if it is so secret, perhaps there is something secret inside.' They entered and saw a small office where all the encryption was produced during not only the civil war but in the years right afterwards."

Inside were around two dozen historic Enigma machines.

When the Spanish Civil War began in 1936, both Hitler's Germany and Mussolini's Italy sent troops to help the nationalists under Franco. But with the conflict dispersed across the country, some means of secure communication was needed for the German Condor Legion, the Italians and the Spanish forces under Franco. As a result, a set of modified commercial Enigma machines were delivered by Germany.

Britain had first obtained a commercial Enigma machine back in 1927, by simply purchasing one in the open in Germany. The machine was analysed and a diagnostic report written on how it worked.

A key figure in trying to understand it was Dilly Knox, a classicist who had been working on breaking ciphers since World War I.

He was fascinated by the machine and began studying ways in which an intercepted message might in theory be broken, even writing his own messages, encrypting them and then trying to break them himself. But there was no opportunity to actually intercept a real message since German military signals were inaudible in Britain.

However, the signals produced by the machines sent to Spain in 1936 were audible enough to be intercepted and Knox began work.

"Having real traffic was a godsend to him," explains Tony, the historian of GCHQ, who asks only his first name is used. Within six or seven months of having his first real code to crack, Knox had succeeded, producing the first decryption of an Enigma message in April 1937. He continued to decipher more.

The machines used in Spain were modified versions of the commercial Enigma machine. The military machine that would be used by Germany during World War II was an order of magnitude more secure because a plugboard was attached to the front. This added a further layer of complexity and made it unreadable at first.

While more complex military Enigma traffic had not been intercepted in Britain, the neighbouring Poles could hear it.

They had worked on mathematical attempts to crack the code and just before World War II began, the French brokered meetings in which the Poles shared their knowledge with British code-breakers, including Dilly Knox.

This would be a crucial step in the journey that led to the cracking of the military Enigma code at Bletchley Park during the war, and the flow of so-called "Ultra" intelligence it produced.

The experience in Spain was a vital stepping stone.

Enigma-type machines were also used as part of the decoding process

"It gave them the foundations and it gave them the confidence that however more complicated the German military Enigma was - and in particular the German Naval Enigma - it was a resolvable problem," explains Tony of GCHQ. "It was something that would not defeat them."

When news of the discovery emerged a few years ago, Tony got in touch with Spanish counterparts asking if it would be possible to obtain some of the machines, and after a lengthy process the handover was completed of these two. One will be held at GCHQ, another at Bletchley Park, where it will be on public display.

The traffic is not all one way. In return the UK handed over a number of items including a German four rotor Naval Enigma machine recovered from Flensburg in May 1945, an Enigma rotor box and related documents. The idea is that this could serve as the foundation of a display on code-making and code-breaking at the Spanish Army Museum, where the ceremony took place on Thursday morning.

Spain's relatively new army museum is housed in the spectacular Alcazar in Toledo. Once a fortress, it was largely destroyed in a famous siege during the Spanish Civil War, before being rebuilt by Franco. In the entrance hall of the museum, the layers of history are evident with walls dating back to Roman times which were then built on in the 11th Century and after up to the present.

The Alcazar was destroyed in the Civil War

The relationship between past and present was one theme emphasised by Iain Lobban of GCHQ. "Today shows there is something timeless about the practice of code-making and code-breaking," he says.

The emergence of the Enigma machine had marked the start of the electromechanical era in encrypting communications. Previously manual ciphers could be cracked by pen and paper but with Enigma the first computers were required.

That situation, Lobban argues, is analogous to the modern era with the advent of the internet and digital technology which is, as with the 1930s and 1940s, requiring a combination of partnerships, cutting-edge technology and human skills of the type Dilly Knox embodied.

"The computer and the internet have combined to produce new challenges in intelligence and security which require transformational changes in our organisations if we are to continue to be as successful in the 21st Century as we were in the 20th. We must become deeply technological organisations," he told the Spanish audience on accepting the two machines.

The emphasis on the importance of working with allies - as shown in British co-operation with Poland in 1939 - was also stressed by the Spanish.

"In today's world it is impossible to work alone," says Mr Sanz.

"You need friends and allies. I knock at the door of the British intelligence - all three agencies - as many occasions as I need it and I always get a response. And I hope on the occasion where the British services knock at my door, when they leave my house they leave with a sense they have been helped also."