Germans can't escape their Lutheran past

- Published

Anxieties among Germans about bailing out European partners have Lutheran echoes from the 16th Century.

I was walking across a bridge over the River Spree in the heart of Berlin, hoping for a rare meeting with the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, when it occurred to me that there was a strange coincidence about Germany and great European projects.

Exactly 500 years ago, one of Europe's greatest thinkers was getting increasingly worried that good German money was being wasted.

Cash was heading to the Mediterranean, subsidising a bunch of badly behaved foreigners.

The 16th Century German thinker was Martin Luther and he was desperate to stay part of that great European project known as the Roman Catholic Church, but equally desperate not to support those who were ripping off German believers to pay to build St Peter's in Rome.

The unfairness of the abuses fed popular resentment until German patience finally snapped. Luther broke away from his beloved Catholic Church, "protesting" in that great rebellion we know as the creation of Protestant-ism, the Reformation.

Nowadays, Germans - even those who are Catholic or non-Christian - cannot escape the Lutheran past.

It's also the Lutheran present. The most powerful woman in the world, Angela Merkel, is a Lutheran believer, the daughter of a pastor. The new German president, Joachim Gauck, is a former Lutheran pastor.

And that cliche of "the Protestant work ethic" - hardworking German taxpayers, even if they are not actually Protestant, continue to bail out the euro while being caught in a squeeze as acute as Luther in the 16th Century.

In their hearts, from Merkel to the car worker on the Volkswagen assembly line, the German people are desperate to be good Europeans, just as Luther was desperate to be a good Catholic.

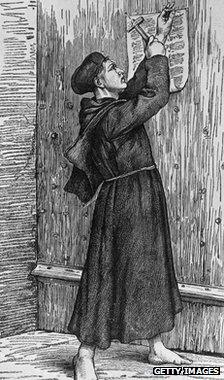

Luther nailed his theses on to the church door in Wittenberg

But in their heads, most Germans suspect there may be something wrong - something morally wrong as well as economically dangerous - about giving money to those who, in the German view, have been at best reckless and at worst dishonest.

In Luther's home town of Wittenberg, just along from the church where in 1517 he nailed his famous 95 Theses rebelling against the Pope, members of the church choir practised their hymns and then told me that it was right for Lutherans to help other Europeans, a Christian virtue, but that the "other Europeans" needed to behave responsibly. And they had not behaved responsibly, which was, some said, increasingly irritating.

It was with the choir's comments - and their hymns - still ringing in my ears that I walked over that bridge towards the chancellor's office just across from the Reichstag.

Frau Merkel greeted me warmly, but in typical fashion told me directly that she rarely gave interviews, that my time was very limited, and we had better get on with it.

Our businesslike conversation reminded me of all those virtuous adjectives - pure Luther - that I learned in my first German lesson - sparsam, treu, ehrlich, ernst, streng - thrifty, straight, honest, serious, strict.

In fact, the pastor's daughter from Hamburg sitting in front of me sounds exactly like the grocer's daughter from Grantham - Margaret Thatcher. Their values - and their view of home economics - could almost be interchangeable.

I suggested to her that when she talks of thriftiness and responsibility (which she does a lot) then many British people will agree with her, which is why so many Britons are sceptical about the euro and suspect it might fail.

Those thrifty Germans are bailing out those who have shown no talent for thrift in the past. This, of course, was an argument Mrs Merkel - the Good European - cannot really accept.

Despite the legacy of the war, the divisions of the euro, and the cliches in British and German tabloid newspapers, I left the Chancellery thinking how much Britain and Germany really have in common.

On the way out, I watched the chancellor of Germany inspect a military guard of honour - soldiers marching with Prussian precision in defence of a young German democracy, a new Germany, really just 20 or so years old.

I was struck by Mrs Merkel's political genius - quiet, cautious, the Hausfrau of her nation, so unlike the noisier, catastrophic male German leaders of the first half of the 20th Century.

The puzzle now is when her political decision to be a good European collides with her Lutheran conscience not to reward bad behaviour or be reckless with money.

I wondered whether for Frau Merkel, like Martin Luther, another reformation in Europe might be on the cards - not tomorrow, perhaps, but one day.