Five Titanic myths spread by films

- Published

It is the tragic story that everybody knows the end to - the doomed Titanic sinks. Its final hours have become the stuff of myth - but how much have the various film versions of the story helped to create and reinforce these legends?

One hundred years ago RMS Titanic raced into an iceberg at almost full speed. Two-and-a-half hours later, it sank to the bottom of the Atlantic with the loss of over 1,500 men, women and children.

It has inspired a host of films, documentaries and conspiracy theories.

The re-release of James Cameron's 1997 blockbuster in 3D is a reminder that many people's knowledge of the events of 14 April 1912 comes not from historical fact, but the silver screen.

'Unsinkable'

In Cameron's Titanic, the heroine's mother looks up at the ship from the dock in Southampton and remarks: "So, this is the ship they say is unsinkable."

But this is perhaps the biggest myth surrounding the Titanic, says Richard Howells, from Kings College London.

"It is not true that everyone thought this. It's a retrospective myth, and it makes a better story. If a man in his pride builds an unsinkable ship like Prometheus stealing the fire from the gods... it makes perfect mythical sense that God would be so angry at such an affront that he would sink the ship on its maiden outing."

A clip from the film Atlantic (1929) - one of the first British films made with sound and a thinly-veiled retelling of the Titanic disaster

Contrary to the popular interpretation the White Star Line never made any substantive claims that the Titanic was unsinkable - and nobody really talked about the ship's unsinkability until after the event, argues Howells.

Although the sinking of the Titanic happened around 15 years after the birth of cinema, and the disaster featured heavily in the silent newsreels of the day, there was very little footage of the ship itself.

This was because the Titanic was not big news before it sank. Its sister ship the Olympic effectively stole the limelight on its maiden voyage from Southampton to New York in 1911. It had the same captain as the Titanic, travelled the same route, had the same safety facilities and the same number of lifeboats - or lack thereof.

Olympic's hull "was painted a light grey purely so that it would look fantastic in the news reel footage", says John Graves, from the National Maritime Museum in London.

Some of this footage was used for the Titanic newsreel after the disaster, but with any telltale signs scratched or inked out.

Simon McCallum, archive curator at the BFI, believes this misrepresentation "fed into the conspiracy theories and mysteries around [the Titanic]. Film makers could project their own narratives and agendas on the event from the get-go".

"History turned into myth within hours and certainly days of the sinking," agrees Richard Howells.

The band's final song

One of the most vivid images to feature in many of the Titanic films is of the band playing as the ship sinks. The story goes that the musicians remained on deck, in an attempt to keep up passengers' spirits - and the last tune they played was the hymn Nearer, My God, To Thee. None of them survived, and they were celebrated as heroes.

The Daily Mirror's front page of 20 April was reproduced as a postcard: "Bandsmen heroes of the sinking Titanic play 'Nearer, My God, To Thee' as the liner goes down to her doom."

Simon McCallum says eyewitness accounts suggest the band did play on the deck, but there is debate about what their final song was - with many accounts describing how the band played ragtime and popular music.

"The passenger that recalled that particular hymn being played was lucky to get away quite some time before the ship sank. We will never really know as all seven musicians perished - but it's poetic licence. Nearer, My God, To Thee is such an evocative hymn that works as a romantic image in film," McCallum says.

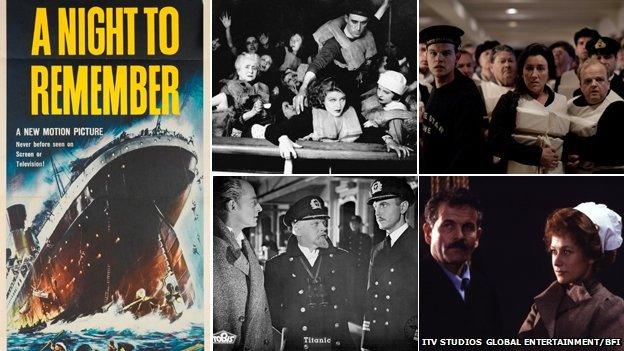

Paul Louden-Brown, from the Titanic Historical Society, worked as a consultant on James Cameron's film. He says that the musician scene in the 1958 film A Night To Remember was so beautifully crafted that Cameron decided to repeat it in his film.

"He told me, 'I stole that entirely and put that into my film, because I loved it, it was such a strong part of the story.'"

Death of Captain Smith

Little is known about the final hours of Captain Smith, but he is remembered as the hero, despite apparently failing to heed ice warnings, and not slowing his ship when ice was reported directly in his path.

"He knew how many passengers and how many spaces were in the lifeboats, and he allowed lifeboats to leave partially filled," says Louden-Brown, who doesn't accept the rosy portrayals of the captain on celluloid.

In the flat, calm conditions that night, the first boat to leave Titanic's side, with a capacity of 65, is said to have contained just 27 people. Many of the lifeboats went off half empty and didn't come back to pick up survivors.

"History records him as dying a heroic death. Statues were erected in his memory. There were postcards produced and stories of him swimming through the water with a child in his arms, saying 'good luck, lads, look after yourself'… all of which never happened," adds Louden-Brown.

"Captain Smith is ultimately responsible for all the failures of the command structure on board, nobody else can take the blame."

Captain Smith did not issue a general "abandon ship" order - which meant many passengers would not have realised the Titanic was in imminent danger. There was no plan for an orderly evacuation, no public address system, and no lifeboat drill.

John Graves agrees that on that fateful night "Smith seems to have vanished into the ether".

He thinks that the captain may have become traumatised when he realised there were insufficient lifeboats.

"His possibly unclear state of mind is illustrated by the fact that he got the design of the Olympic and Titanic mixed up. The latter's promenade deck was enclosed in part, yet he ordered lifeboats to be boarded from that deck, rather than from the boat deck."

Villainous businessman

The stories surrounding J Bruce Ismay, the president of the company that built the Titanic, are many but almost all centre on allegations of his cowardice in escaping the sinking ship while fellow passengers, notably women and children, were left to fend for themselves.

All of the screenplays, including the new TV series written by Julian Fellowes, portray Ismay as a coward who bullied the captain into driving the ship too fast and then saved his own skin by jumping into the first available lifeboat.

"Every single film-maker has found that betrayal to be too delicious not to incorporate into their film," says Paul Louden-Brown.

"If you go back to the genesis of where that came from, it goes back to William Randolph Hearst, the big newspaper magnate in the US. He and Ismay had fallen out years before over Ismay not cooperating with the press with regard to an accident that happened to a White Star Line ship."

Ismay was almost universally condemned in America, where the Hearst syndicated press ran a vitriolic campaign against him, labelling him "J Brute Ismay". It published lists of all those who died but in the column of those saved it had just one name - Ismay's.

Some survivors said he jumped on the first lifeboat, others that he had demanded his own crew to row him away and the ship's barber said that Ismay had been ordered into a boat by the Chief Officer.

Lord Mersey, who led the British Inquiry Report of 1912 into the loss of the Titanic, concluded that Ismay had helped many other passengers before finding a place for himself on the last lifeboat to leave the starboard side.

"Had he not jumped in he would merely have added one more life, namely, his own, to the number of those lost," he said.

The 1943 German film Titanic, commissioned by the Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, portrays Ismay as a power-mad Jewish businessman who bullies the brave, Teutonic captain into driving the ship too fast through the ice despite being warned that this is reckless.

The 1958 film A Night to Remember, long regarded as the most historically accurate of the Titanic films, also portrays Ismay as the villain.

Louden-Brown believes this to be unfair, and raised the issue with James Cameron when he was working with him as a consultant. In Cameron's film Ismay uses his position to influence the captain to go faster with the prospect of an earlier arrival in New York and favourable press attention.

"Apart from being told, under no circumstances are we prepared to adjust the script, one thing they also said is 'this is what the public expect to see'," Louden-Brown says.

Ismay never overcame the shame of jumping into a lifeboat and retired from the White Star Line in 1913, a broken man.

Frances Wilson, author of How to Survive the Titanic: The Sinking of J Bruce Ismay, says she feels sympathetic towards Ismay and sees him as "an ordinary man caught in extraordinary circumstances".

"He was emotionally completely unequipped for what he was to go through... His confused and confusing behaviour on the Titanic was due to the confusion around his status - was he an ordinary passenger, as he claimed, or as the inquiries suggested a 'super-captain'? People on ships act according to rank and Ismay had no idea of what his rank was."

The Titanic's 20 lifeboats had capacity for only 1,178 people

Steerage passengers

One of the most emotive scenes in Cameron's Titanic portrays the third class passengers as being forcibly held below the decks and prevented from reaching the lifeboats. Richard Howells argues that there is no historical evidence to support this.

Gates did exist which barred the third class passengers from the other passengers. But this was not in anticipation of a shipwreck but in compliance with US immigration laws and the feared spread of infectious diseases.

Third class passengers included Armenians, Chinese, Dutch, Italians, Russians, Scandinavians and Syrians as well as those from the British Isles - all in search of a new life in America.

"Under American immigration legislation, immigrants had to be kept separate so that before the Titanic docked in Manhattan, it first stopped at Ellis Island - where the immigrants were taken for health checks and immigration processing," Howells says.

Each class of passengers had access to their own decks and allocated lifeboats - although crucially no lifeboats were stored in the third class sections of the ship.

Third class passengers had to find their way through a maze of corridors and staircases to reach the boat deck. First and second class passengers were most likely to reach the lifeboats as the boat deck was a first and second class promenade.

The British Inquiry Report noted that the Titanic was in compliance with the American immigration law in force at the time - and that allegations that third class passengers were locked below decks were false.

Evidence given at the inquiry did suggest that initially some of the gates blocked the way of steerage passengers as stewards waited for instructions and that they were then opened, but only after most of the lifeboats had launched.

Lord Mersey noted that third class passengers were "reluctant" to leave the ship, "unwilling to part with their baggage", and had difficulty getting from their quarters to the lifeboats.

None of the evidence presented pointed to any malicious intent to obstruct third class passengers - but rather an oversight caused by unthinking obedience to the regulations, but the results were still deadly.

When the lifeboats were finally lowered officers gave the order that "women and children" should go first. One hundred and fifteen men in first class and 147 men from second class are recorded as having stood back to make space available and as a result died.

No third-class passengers testified at the British inquiry but they were represented by a lawyer, W D Harbinson, who concluded that: "No evidence has been given in the course of this case that would substantiate a charge that any attempt was made to keep back the third class passengers."

Class did make a difference however - less than one third of steerage passengers survived, although women and children survived in greater numbers across all classes as they were given priority on the lifeboats.

Additional reporting by Melissa Hogenboom.

- Published15 April 2013