What are spies really like?

- Published

Most people have watched a spy film, but few have ever met someone from the intelligence community. So how close are real spies to the Bournes and the Bonds? Peter Taylor looks at the world of the modern day secret agent.

From James Bond to Spooks, from Jason Bourne to Tinker Tailor, spying is big box office business. Its vocabulary has become familiar to us all, from "stings" and "moles" to "dead letter drops" and "honey traps".

The fact is that the image of such operations as depicted on the big and small screens - and in airport blockbusters too - is firmly rooted in reality. The "tradecraft" is common to both the fictional and real world of spying.

But those who actually carry out these covert and potentially dangerous operations could not be further removed from their imaginary counterparts, as I found out when I interviewed serving officers from MI5 (the domestic Security Service) and MI6 (the overseas Secret Intelligence Service).

Recruiting and running agents is the most dangerous and demanding part of being a modern spy. That's what Michael does for MI6. He works in al-Qaeda's heartlands - the precise locations of which are confidential for security reasons.

"Our ability to get inside these terrorist networks is critical to give us advance warning of the threats that we face", he says.

So how does he go about it?

"We'll start with a targeting process. Our objective is to get as close to the top as we can. We'll look to map out what we can about that terrorist network, understand who the key figures are, the connections between them to try and get a real sense of who the individuals are in this particular network.

"Could we get alongside them? Are they accessible? Would they have access to information that would be useful to the government? Do we think that they might be motivated to work with SIS (MI6) as a covert source?"

Life on the edge for fictional spy James Bond

And how does Michael go about the actual process of recruiting?

"It's the job of our officers to think: 'Under what guise could I approach this individual? What's the best means of developing a relationship with them?'. Each approach will be tailored to the particular agent, or prospective agent and over time persuade them to work with SIS."

Motivations might include disillusionment with al-Qaeda's violent ideology, a desire to live in the UK, or money.

He admits the initial approach made to a potential agent is a heart-in-mouth moment.

"When you're in some dusty outpost in semi-governed space, about to meet for the first time a contact within a terrorist organisation you've brokered, that is nerve wracking. There are risks involved in everything we do. I don't think we'd get very far if we were risk averse. We have to do what we can to mitigate them."

There is a myth that to be a modern spy you have to come from the dreaming spires of Oxbridge. But it is patently untrue.

Shami, an MI5 surveillance officer, thought he never had a chance of being recruited. He'd never been to university.

"My understanding was that you had to be upper class, academically bright and white male generally. I just felt I had nothing to offer."

Nevertheless he applied online via the MI5 website and to his amazement, after rigorous assessment, was offered a job. After his final interview, his recruiters shook his hand and said "congratulations".

Although Shami hadn't recognised it, he was exactly the kind of person MI5 was looking for to carry out the surveillance that is invariably the starting point for investigating any suspected terrorist cell.

Shami is streetwise, smart and can easily blend in to any community.

Surveillance, both human and technical, was the bedrock of the covert operations that led to the conviction of the Islamist cells that were planning to make fertiliser bombs to attack London and the South East of England, and liquid explosives to bring down aircraft over the Atlantic.

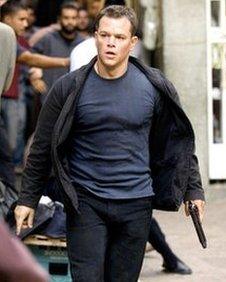

Matt Damon played soldier-turned-CIA assassin Jason Bourne

Anonymity is the key to the way in which Shami operates.

"You're constantly analysing your own behaviour as well as the behaviour of others. The clothes you're wearing, how you're walking and how you're talking, are all factors that you constantly have to be thinking about.

"You've got to blend in. You have to be 'Mr Grey' - a nobody, a person you might pass on the street but you'd forget in a second."

He admits he gets a "buzz" from it and says his greatest fear is "missing a vital bit of information that will go on to cause loss of life". His greatest satisfaction is "the arrest of the individuals we're up against".

Emma is an intelligence officer who works at MI5's headquarters with people like Shami who are out on the ground. Like Shami, her preconception of MI5 was wide of the mark.

"I thought it would be largely male, and women would usually be a PA or Miss Moneypenny from James Bond."

She works on an al-Qaeda-related investigations team and her job is to analyse intelligence coming in from a variety of different technical and human sources - and from partner agencies.

"It's really like piecing together a jigsaw."

Like Shami, the London bombings of 7 July 2005 were a powerful motivating factor in Emma's wish to join MI5.

"For me, 7/7 was a wake up call about how serious the Islamist extremist problem actually was."

Emma's mother was worried when her daughter told her the news that she was going to join MI5.

"She was rather horrified. She'd watched Spooks and her initial reaction was, 'Oh my goodness, you're going to end up with your head in a fat fryer!'" - a reaction to an early episode in which a young woman MI5 officer is tortured and has her head thrust into a pan of boiling fat.

Emma knows that a vital piece in putting the "jigsaw" together comes from human sources or agents recruited from within suspected terrorist organisations - a standard plot line of Hollywood movies.

"They're often one of the ways in which we can ask the most intelligent and nuanced questions."

But recruiting and running agents can pose potentially life-threatening questions, in case the source being handled turns out to be a double agent.

Channel 4's current Homeland series is based on that intriguing question. In reality too, such possibilities are always there and every precaution is taken to check out that the agent is genuine and not a plant.

Michael sees 007 as pure fantasy.

"The key elements of the James Bond myth is that we're some kind of paramilitary organisation - that's not the case."

And the idea of having a licence to kill?

"No we don't!"

Anna, his MI6 colleague in London confirms this.

"If James Bond actually worked in MI6 today, he'd spend a large amount of time behind a desk doing paperwork and making sure everything was properly cleared and authorised.

"He certainly wouldn't be the lone wolf of the films."