Forty years in solitary confinement and counting

- Published

As two men in Louisiana complete 40 years in solitary confinement this month, the use of total isolation in US prisons is high. What does this do to a prisoner's state of mind?

Robert King paces the front room of his small, one-storey house in Austin, Texas.

"I imagine I could put my cell inside this room about six times," he says. "Probably more."

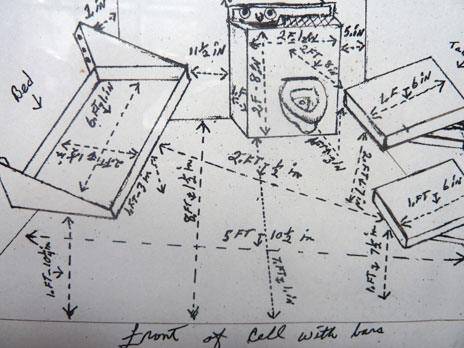

For 29 years Robert King occupied a cell nine feet by six - just under three metres by two - for at least 23 hours a day.

He spent most of his time incarcerated in one of the toughest prisons in the United States - Louisiana State Penitentiary.

The prison, the largest in the US, is nicknamed Angola after the plantation that once stood on its site, worked by slaves shipped in from Africa. King, who was released from prison in 2001, still calls himself one of the Angola Three - three men who have been the focus of a long-running international <link> <caption>justice campaign</caption> <url href="http://www.angola3.org/" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

Between them, they have served more than 100 years in solitary. All three say they were imprisoned for crimes they did not commit, and where convictions were only obtained after blatant mistrials.

King has the open face, lean physique and broad chest of a man in good shape, even on the cusp of his 70th birthday.

And he is reluctant to delve too deeply into what those years in solitary were like, beyond saying that "it's impossible to get dipped in waste and not come up stinking".

There is, he says, a physical toll to long-term isolation: "People become old and infirm before their time."

But more, there is a psychological effect. He stayed strong, he says, but it was "scary" to see how others crumpled through lack of human contact.

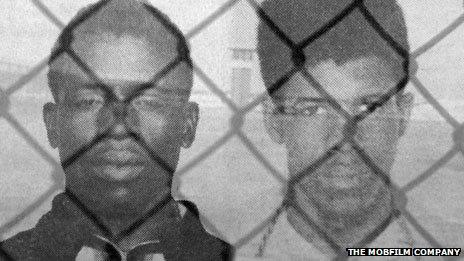

Robert King spent nearly three decades in solitary confinement in the Louisiana State Penitentiary

Angola in the 1960s and 1970s was a place known for its brutal forced labour, its sexual slavery and its violence. Even so, Robert King is on record as saying that solitary was much, much worse.

His reticence is not matched by Nick Trenticosta, the lawyer for the other two members of the Angola Three - Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox.

"I have interviewed a number of of people who've spent 10-12 years in solitary confinement," says Mr Trenticosta, in his basement legal offices in New Orleans.

"Almost all of the people are severely damaged. They're potted plants. Their will to live really doesn't exist any more.

"They become shells of their former selves. If I take them to the visitors' area, it'll be two hours before I can get an answer to my questions, and then I might just hear gobbledygook."

Back in the early 1970s, Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox were already in Angola, serving time for armed robbery.

Herman Wallace's sketch of the dimensions of his cell

They became involved in the Black Panther Party - they say in order to try to improve the abysmal conditions for prisoners. Then in 1972, a prison guard called Brent Miller was murdered.

Wallace and Woodfox were convicted, and placed in solitary - where, apart from a short spell in 2008 in a high security dormitory, they have remained ever since.

Both men have always maintained their innocence - saying that grave questions were raised about an inmate being secretly rewarded for his incriminating testimony, and pointing to the lack of forensic evidence linking them to the murder.

Wallace's sister Vicky lives on the poor side of New Orleans, in the lower ninth ward. Her health has, she says, suffered from the constant worry about her brother - and he is not in good shape either.

"He need to talk to a psychiatrist," she says.

When she does get to visit him "he slips sometimes, when we talking," she says.

"His ears are not so good at all. His ear is hard like this table," she says, knocking on her wooden dining table, "because it looks like they beat him so much."

Neither the Department of Corrections - the US prison service - or the state attorney general's office were available to speak about the case of the Angola Three or the use of solitary confinement.

But in the town closest to Angola - St Francisville - chief of police Scott Ford was clear on the matter.

"I absolutely don't mind if somebody who took the life of somebody's loved one doesn't see but an hour of sunlight a day.

"I'm probably a little more on the other side that says that one hour that you are letting them see sunlight, if we could shave some time off that, it would be better."

Reliable figures on the numbers held in solitary in the US are hard to come by.

What does seem clear is that in that recent decades, the number has grown hugely, into the tens of thousands, as some states put greater emphasis on solitary confinement, and the overall prison population rises. Campaigners put the figure at 80,000.

Compare this estimate to a statement to the BBC from the Prison Service of England and Wales: "At any one time there would only be a small handful of exceptionally dangerous prisoners held in these conditions (under five)… prisoners are never left in an isolated state for long periods of time."

The practice may have hit its high-point in the US. "Supermax" maximum security prisons are very expensive. Isolation units within them, all the more so.

So as money dries up, so there may be pressure to put fewer prisoners in solitary. The case of the Angola Three has won the support of organisations such as <link> <caption>Amnesty International</caption> <url href="http://www.amnesty.org/en/appeals-for-action/justice-for-albert-woodfox-and-herman-wallace" platform="highweb"/> </link> .

And the former Chief Justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court, Pascal Calogero, suggests there could be room for a legal challenge to the practice.

The use of extended solitary is not, he argues, provided for in law.

"It is beyond what the legislature has directed should be imposed for a felony conviction. And excessiveness in this regard cannot be in accordance with the law."

Jean Casella, of the campaign group Solitary Watch, puts it more starkly: "It's torture, when it goes beyond a few days or a few weeks."

She cites the testimony of people such as Senator John McCain, who spent years in solitary as a prisoner of war in Vietnam.

And the prisoner in a supermax in Illinois, who said: "Lock yourself in your bathroom for 10 years, then come out and tell me that that's not torture."

Herman Wallace is 70. Albert Woodfox is 65. In the middle of this month, they will each have spent 40 years in solitary.

<bold>Listen to the full report on </bold> <link> <caption>Crossing Continents</caption> <url href="http://bbc.in/nzJbIH" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold> on </bold> <link> <caption>BBC Radio 4</caption> <url href="http://bbc.in/qd934Q" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold> on Thursday, 5 April at 11:00 BST and Monday, 9 April at 20:30 BST. </bold>

<bold>You can also hear the report on </bold> <link> <caption>Assignment</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p002vsn0" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold> on the </bold> <link> <caption>BBC World Service</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold>. </bold>

<bold>Listen again via the </bold> <link> <caption>Radio 4 website</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b01f67yb" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold> or the Crossing Continents </bold> <link> <caption>podcast</caption> <url href="http://bbc.in/rkM8x9" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold>.</bold>