Gustav Klimt: What's the secret to his mass appeal?

- Published

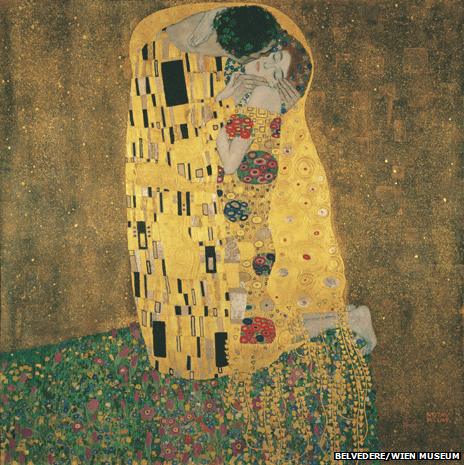

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of Gustav Klimt. The Austrian painter's most famous work, The Kiss has become a staple on university residence walls, but what is it about Klimt that garners such mass appeal?

Paintings by Klimt are among the most expensive in the world but they have also come to adorn the cheapest tat - everything from mugs and fridge magnets to key-rings and tea towels.

One of his works, the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, even has a Barbie doll made in its image.

"It's quite extraordinary the way the 'Klimt factor' has taken off," says art critic Richard Cork. "He's one of those artists - and there aren't many - who gets his repros everywhere.

"It's like an extraordinary contagion but of course it's more positive than that, it's a whirlwind. Everywhere you look, there's a Klimt. You can't escape him."

His popularity, says Cork, is due to him being on the one hand very avant-garde in his day, experimenting with new things, and on the other hand dealing with subjects that have very wide appeal.

"He has very sensuous appeal and people respond to that almost instinctively. He pushes his paintings towards abstraction but how he does it is to fill a lot of them with patterns and this pattern-making has this kind of allure."

There's a sense of freedom about Klimt's work, he adds, and an uplifting quality that people relate to.

"People like gold," says Dr Alfred Weidinger, one of the foremost experts on Klimt. "It is this metallic aspect that people are attracted to."

Weidinger is the vice-director of the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, which holds the world's biggest collection of Klimt. Over the course of his career, Weidinger has found the artist's appeal to be truly global.

In 2009 Weidinger was travelling around Africa taking photographs when he met a woman in the deep rural south of Ethiopia - a place where tourists rarely go - who was wearing a T-shirt of Klimt's The Kiss.

She explained that an Italian photographer who had visited her village earlier that year offered her a choice of three T-shirts as a thank-you gift. Although she knew nothing of the artist, she chose the Klimt because she loved the gold in the image.

As the son of a goldsmith, Klimt understood metals like few other artists of his generation. Though he worked with paint, he had a unique ability to create the illusion of precious metals, stones and jewels.

He trained at the commercially-minded School of Applied Art, not at Vienna's fine art academy.

"He wanted to use marble, real gold and real silver," says Weidinger, but rarely could he or his patrons afford them.

But when money was no object, Weidinger says, Klimt's true colours were revealed.

He was asked to create a mosaic frieze for the mansion of a wealthy banker, Adolphe Stoclet, and he encrusted it with jewels, enamel, mother of pearl, silver and gold.

In his paintings Klimt recreated the sumptuous grandeur of the Stoclet Palace.

"You can feel behind the paintings, the will to make something precious," says Weidinger.

Not just a master of the metallic, Klimt was also a master of his own marketing.

He was one of the only artists in Austria to do extensive, authorised reproductions of his own work. And he allowed others to reproduce his work too.

But to reduce Klimt's work to its decorative appeal is to ignore its radicalism. He was the leader of the Secession movement, a group of Viennese artists who challenged the rigidity of traditional Austrian painting.

Their main aim was to bring art, craft and design together in one great movement, the Gesamtkunstwerk. It was heavily influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain, characterised by the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh whose decorative style also reached a mass audience.

Klimt's life-long friend and supposed lover Emilie Floege was involved in the movement as a dressmaker and one of the main couturiers in Vienna. Her work is thought to have influenced the opulent textiles depicted in Works like The Kiss.

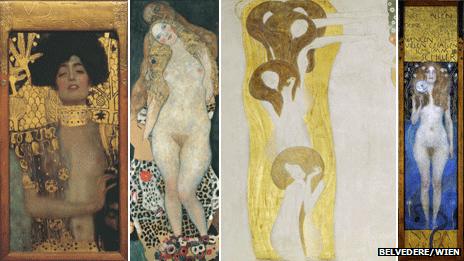

Floege was only one of Klimt's many lovers. Though he was a shy man he reputedly loved women and after 1900 painted them almost exclusively.

Many of his women were painted in the nude, in evocative and erotic positions that emphasised sensuality and sex. They brazenly confronted the viewer with their gaze as well as their nudity.

They were controversial images but appealed to a new sensibility, a celebration of sexuality that was only just emerging in a city and a society that was the playground of another famous Austrian, Sigmund Freud.

In 1905 Freud published Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, a book that was to profoundly challenge attitudes to sex.

Like Freud, Klimt wanted to put sexuality in the public sphere.

But in 1903 he was forced to remove one of his paintings, Hope I, from the first retrospective of the Secession movement. The picture, which showed a naked pregnant woman staring unabashedly out from the canvas, went far beyond the boundaries of propriety.

Perhaps this radical spirit is something that later generations of young people have identified with.

"Nobody was able to synthesise feelings like love, passion or desire but also despair and anxiety like Klimt," says Klaus Pokorny of the Leopold Museum in Vienna. "That's why he is so fascinating for younger people."

"Another reason is his capability to catch harmony and lust but not least his art is very, very decorative."

But any artist that becomes as ubiquitous as Klimt risks being over-exposed, says Cork.

"There's what I call the Mona Lisa problem, which is that if a painting is reproduced everywhere and there's no escape you get fed up with it.

"I can't look at the Mona Lisa any more. I look at it but can't react to it. Sometimes I do get like that with Klimt, when I'm in a birthday card shop.

"It's better to go back to Vienna and see the real thing."

<link> <caption>The Strand</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p002vsn3" platform="highweb"/> </link> <italic> from the </italic> <link> <caption>BBC World Service</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/" platform="highweb"/> </link> <italic> travelled to Vienna to mark the 150th anniversary of Klimt's birth. Listen to the programme </italic> <link> <caption>here</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00q86dy#p00qj2h7" platform="highweb"/> </link> <italic>.</italic>

- Published24 February 2012