Are you a Luddite?

- Published

- comments

They burned down mills in the name of a mythical character called Ludd. So 200 years after their most famous battle, why are we still peppering conversations with the word "Luddite"?

It's a popular retort to someone struggling to operate their new smartphone or refusing to buy the latest gizmo: "You're such a Luddite."

There is another word for it - technophobe - but it doesn't convey the same sense of irrational hostility to the modern world. So where did "Luddite" come from?

In the midst of the British industrial revolution, skilled textile workers feared for their jobs. An uprising began in 1811 when Nottinghamshire weavers attacked the new automated looms that were replacing them.

The workers took inspiration from a fabled General Ludd or King Ludd living in Sherwood Forest. His fanciful name may have come from a young Leicestershire weaver called Ned Lud, who in the late 18th Century was rumoured to have smashed two stocking frames.

Scene of the crime: The "original" Luddites attacked Rawfolds Mill in 1811

The machine breaking spread to West Yorkshire wool workers and Lancashire cotton mills, in what the historian Eric Hobsbawm called "collective bargaining by riot". Machinery was wrecked, mills were burned down and the Luddites fought pitched battles with the British Army.

The response of the state was brutal. Machine breaking became a capital offence. At trials in York, 17 Luddites were hanged and another 25 transported to Australia, while in Lancaster eight were hanged and 38 sentenced to transportation.

One of the most serious incidents happened two hundred years ago this month. About 150 Luddites armed with hammers and axes attacked Cartwright's mill in Rawfolds, near Huddersfield. The authorities shot two of them dead and the attack was eventually repelled.

For Katrina Navickas, author of Loyalism & Radicalism in Lancashire 1798-1815, they were working class heroes. Trade unions had been banned in 1800 and here was another way for workers to defend their livelihoods.

There's no doubt that the Luddites have been romanticised, says Dr Emma Griffin, author of A Short History of the British Industrial Revolution. They are thought of as the first workers to destroy their machinery, yet this had been going on for years. What marks the Luddites out was that they were better organised than their predecessors, she says.

But both historians agree that today's use of "Luddite" is wrong. To use the term for someone who ignores Twitter or refuses to move from analogue to digital TV is a complete misrepresentation, says Griffin.

"We use it for people who are hostile to technology, who don't want to get a mobile phone," she says. "But what concerned the Luddites about technology was that it was going to cut their wages."

An accurate modern example, according to Griffin, is the 1986 battle of Wapping when print unions picketed Rupert Murdoch's new hi-tech newspaper offices in protest at the computerisation they feared would make them obsolete.

So how did the word evolve so much?

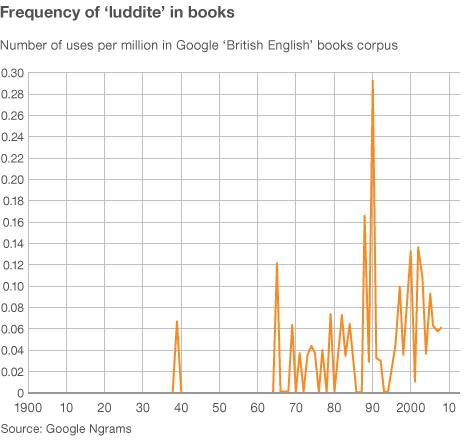

The first recorded usage of Luddite in the Oxford English Dictionary is for 1811. But its catch-all anti-tech meaning appears to be a relatively recent phenomenon. According to the OED, it wasn't until 1970 that the term was used - by the New Scientist - to describe technology refuseniks.

Jonathan Franzen, Prince Charles and the band Oasis have all been dubbed "Luddites"

But soon this meaning was everywhere. In 1984 the novelist Thomas Pynchon wrote an essay asking <link> <caption>"Is it OK to be a Luddite?"</caption> <url href="http://www.nytimes.com/books/97/05/18/reviews/pynchon-luddite.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> for the New York Times Book Review.

The debate has never been quite resolved, for the desirability of being a Luddite is a matter of personal taste. A common boast in the 1980s was that one couldn't programme the video. But for others "Luddite" is a useful putdown for Neanderthal technophobes that can be laced with different quantities of humour or contempt.

"Will mainframes attract the same hostile attention as knitting frames once did?", Pynchon wondered in his essay. "I really doubt it. Writers of all descriptions are stampeding to buy word processors."

And yet a neo-Luddite movement sprang up. The most extreme expression of this philosophy was the bombing campaign of Ted Kaczynski, also known as the Unabomber, who was sentenced to life imprisonment. His manifesto, which was eventually published by the New York Times, said that the "Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race".

Today with digital technology enlivening or intruding on - depending on your view - day-to-day experiences, the term is more popular than ever. People nostalgic for a time before mobile ringtones had colonised train carriages may class themselves as Luddites.

But whereas once it was cool for kids not to understand science, the tide now appears to be with the nerds and geeks. Luddite may sometimes be a fond term but its adherents are on the losing side.

The sheer variety of situations in which "Luddite" can be used would astonish the attackers of Cartwright's Mill were they to resurface today.

In recent years, the term has been used for opponents of planning reform, ID cards, Tesco and goalline technology. Prince Charles is a target, as is the novelist Jonathan Franzen - after an attack on e-books and Twitter - and Oasis were once described by fellow band Bloc Party as "repetitive Luddites".

Historians may bridle at such an inexact use of the word but it's too late, says Mark Forsyth, author of The Etymologicon: A Circular Stroll through the Hidden Connections of the English Language.

"There's absolutely no point historians getting indignant about language. It's never going to stop changing - they're trying to hold back the tide like the Luddites."

And "Luddite" is not unique. Many historical terms are bandied about casually, losing their precise meaning. "People have a "cavalier" attitude," Forsyth points out. "There are 'puritans' all over the place. And 'bolshie' is a bit of a classic."

None of this means that contemporary Britain is awash with supporters of Charles I, hardline Calvinists or Bolshevik revolutionaries. But these colourful terms add to the richness of the English language, he says.

For lexicographer Susie Dent, the evolution or "transferred" meaning of "Luddite" reminds her of how "philistine" has changed. "The figurative sense to mean an uneducated or unenlightened person is from 1825. Before then, the first transferred sense was an often humorous reference to a group regarded as one's enemies."

These new allusions are quite common, she says. "But what always strikes me is their endurance, centuries beyond their original application."

Navickas makes a point of correcting people, albeit in a lighthearted way, when she overhears them misusing "Luddite". And yet she is thankful for the frequent sloppy usage, as it keeps these textile workers' memory alive.

The rural equivalent of the Luddites were farm workers who took part in the Swing Riots of the early 1830s. Ricks were burnt, threshing machines destroyed and tithe barns attacked. But no-one remembers this now for they never developed a recognisable brand, she says.

So however grating it is to hear an iPhone refusenik invoking the weavers of Nottinghamshire, Navickas is glad that "Luddite" remains a popular part of everyday speech.

The irony is that as the speed of technological change accelerates, the term "Luddite" has never been more necessary.