Are North Koreans really three inches shorter than South Koreans?

- Published

It's often been reported that North Koreans are a few inches shorter than their counterparts south of the border. Is that true?

North Korea's recent failure to launch a long-range rocket was embarrassing for its new leader, Kim Jong-un. It was supposed to be a symbol of progress.

Renewed media interest in North Korea since Kim Jong-un replaced his father has prompted the re-emergence of a claim which appears to be a symbol not of progress, but of relative decline: that North Koreans are much shorter than South Koreans.

The Independent reported last week, external that "nothing is small in North Korea apart from the people, who are on average three inches shorter than their cousins in the South".

This statistic, or versions of it, have been quoted for some time. In 2010 the late Christopher Hitchens put the difference at six inches in an article in Slate, external titled "A Nation of Racist Dwarfs".

Senator John McCain referred to a three-inch gap in a 2008 presidential debate, external.

So what's the truth? Professor Daniel Schwekendiek from Sungkyunkwan University in Seoul has studied the heights of North Korean refugees measured when they crossed the border into South Korea.

He says North Korean men are, on average, between 3 - 8cm (1.2 - 3.1in) shorter than their South Korean counterparts.

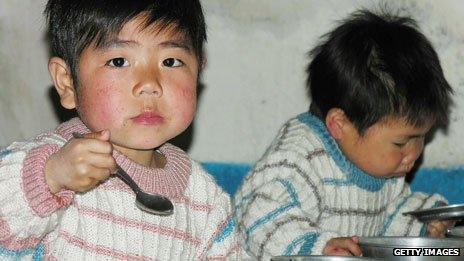

A difference is also obvious between North and South Korean children.

"The height gap is approximately 4cm (1.6in) among pre-school boys and 3cm (1.2in) among pre-school girls, and again the South Koreans would be taller."

Schwekendiek points out that the height difference cannot be attributed to genetics, because the two populations are the same.

"We're dealing with the Korean people," he says, "and Korea is interesting because it basically hasn't experienced any immigration for many centuries."

Martin Bloem is head of nutrition at the World Food Programme, which has been providing food aid to North Korea since 1995. He says poor diet in the early years of life leads to stunted growth.

"Food and what happens in the first two years of life is actually critical for people's height later," he says.

In the 1990s North Korea suffered a terrible famine. Today, according to the World Food Programme, "one in every three children remains chronically malnourished or 'stunted', meaning they are too short for their age".

South Korea, in contrast, has experienced rapid economic growth. Bloem says "economic growth is one of the main determinants of height improvement".

So while North Koreans have been getting shorter, South Koreans have been getting taller.

"If you look at older Koreans," says Schwekendiek, "we now see a situation where the average South Korean woman is approaching the height of the average North Korean man.

"This is to my knowledge a unique situation, where women become taller than men."

The secretive nature of North Korea makes it difficult to find reliable data for analysis.

Schwekendiek has studied refugees, but he rejects the notion that people driven to cross the border to South Korea are the most disadvantaged and therefore most likely to be stunted.

The refugees, he says, "come from all social strata and from all regions".

He has also studied data collected by the North Korean government and by international organisations working in North Korea, which he says support his findings.

It seems that this height statistic reveals a tragic fact - that as South Koreans have got richer and taller, North Korean children are being stunted by malnourishment.