Louis Theroux on dementia: The capital of the forgetful

- Published

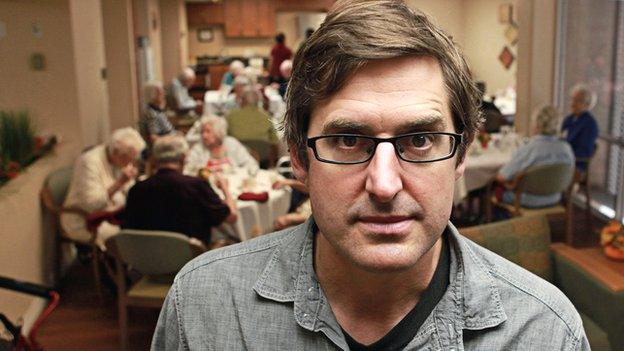

With an ageing population, a wave of dementia is approaching. Caring for those afflicted isn't easy, writes Louis Theroux.

Nancy Vaughan is a charming and lively conversationalist, a friendly host, and at nearly 90, still has much of the sparkle and attractiveness that must have turned many heads when she was in her heyday as a model in New York.

But she also has trouble remembering her own name, or the fact that she is married (62 years and counting), or indeed, much of the time, some of the basics of the English language.

Nancy is in the advanced stages of Alzheimer's.

On a sunny late autumn day I visited Nancy and her husband, John, at their home in Phoenix, Arizona. We made friendly conversation in the kitchen and for moments I could have believed that she was mentally well.

Her smile is still engaging, she is physically fit, and she can sometimes carry on brief exchanges. When I asked if she had any problems with her memory, she said an emphatic "no".

But when John posed the question directly "Nancy, what is your name?" she looked a bit baffled. Asked for her surname, Nancy said "Bread", a little uncertainly. I wondered whether this might be her maiden name, but was told that was Johnson.

Nancy and John's life has become surreal and stressful in many ways. John has taken to wearing a name tag with his name on it to help Nancy identify him.

He has also stuck a copy of their wedding photo up in the kitchen so that, in her confused moments, he can prove to her that they are married.

John cares for Nancy fulltime. They have no children, so there is no family help take the strain - and they are not in the financial position to have Nancy go into a care home.

Aged 88, John is the full-time carer for someone with many of the same needs as an adult-sized toddler.

John and Nancy are by no means exceptional. There is a slow-moving tsunami of dementia advancing towards us as our population ages.

Looking after those with dementia can be a full-time job

It's reckoned that one in eight Americans aged 65 and over has Alzheimer's - the most common cause of dementia. Nearly half of the over 85s has the disease. As medical science has become better and better at prolonging our lives, the mental side of things hasn't kept pace.

Nowhere is this more in evidence than in Phoenix. For years Phoenix has been a mecca for America's elderly, who are attracted by the year-round sun and dry desert heat.

Now increasingly it is a kind of capital of the forgetful and the confused.

Not coincidentally, Phoenix is also pioneering the way dementia sufferers are cared for and treated.

One of the top destinations for people in need of round-the-clock care is Beatitudes, a gated retirement complex, which has, tucked among its many buildings, a memory support annex.

Most of the residents at Beatitudes have seriously impaired memories, to the point where they can no longer look after themselves, are quite often confused, and occasionally have delusions.

It's not uncommon for a resident to imagine that they've seen a non-existent intruder, or to suppose that because they cannot find a purse or wallet, that someone has stolen it.

Partly under the influence of a Bradford University-based psychologist, Tom Kitwood, Beatitudes' carers have a policy of not contradicting - and even playing along with - the delusions of the residents, avoiding confrontations, de-escalating conflicts, and "redirecting" the attention of those in distress, using distractions and pleasurable activities.

Beatitudes staff use medication as little as possible. They try to be flexible and adapt to the quirks of the residents and the symptoms of their condition, letting them wander the corridors at night should they feel urge, letting them bathe, eat and sleep on their own schedule, and offering them snacks and chocolate at any time of the day or night.

I spent the best part of two weeks at Beatitudes, observing their practices first-hand.

One of the people I got to know was Gary Gilliam. A 69-year old, Gary had been a successful dentist in his younger years, as well as doing time in the army.

He'd been at Beatitudes several months when I met him, and though his memory came and went, he spent much of his time under the misapprehension that he was still a practising dentist, stationed at a military base.

Gary was genial and playful, constantly cracking jokes, and so it took me a while to realise quite how advanced his dementia was.

He told me he'd been having some problems with his short-term memory but he had no idea he might be in any kind of care home. But rather than contradict him, the staff would gently go along with Gary's version of reality.

One technique is to avoid challenging those with memory loss

Quite often, especially in the evening, Gary would imagine that his time on "the base" was up. He'd pack his bags and start looking for the exit.

Staff would cajole him into staying another night, saying it was a little late now, it was dark out, better to leave it until morning. Or they might ask Gary to look at their teeth, at which point he would switch into dentist mode and forget his plan.

Gary also had a habit of forgetting that he was married, despite the fact that his wife of nearly 30 years, Carla, was alive and well, and a frequent visitor.

Being one of the few men on his unit, Gary's company was much in demand. He had two girlfriends, who enjoyed cuddling with Gary, though the exact extent of their intimacy wasn't clear.

I had the chance to observe this rather odd love triangle - or "love square", if you include the second girlfriend - when I accompanied Carla on a visit. To my surprise, she suggested that Gary bring one of the girlfriends with him.

She said this would make the visit run more smoothly - seeming to imply that Gary might prefer the company of his new friends over hers - but I was also struck that Carla was keen for me to see and understand the pain and the strangeness of loving someone with Alzheimer's.

Perhaps the most extreme visit I observed during my time at Beatitudes took place between a young man called David Watson and his mother Gail.

Though she wasn't very old, Gail's dementia had progressed very quickly. She was on the fourth floor of the Beatitudes memory support building, home to the most advanced cases.

Gail could no longer speak at all, though she was physically well, and would wander the corridors often picking up objects and approaching people, endlessly repeating a sound that sounded like "gulla".

David tried showing old photos to his mum. He tried stopping her on her perambulations for a hug. There wasn't much sign of recognition that I could see.

David explained that his sisters no longer visited. "Because this is hard," he said. But then, a moment later, David's mother leaned in and held his face in her hands. "So that's why I come and visit," he said, visibly moved. "Because sometimes that happens, and then that's good."

Near the end of my stay in Phoenix, egged on by John, I volunteered to care for Nancy for half a day, hoping to give him some small respite but more importantly to have a small glimpse of what John goes through on a daily basis.

Selinda Border, 49, is suffering from early onset Alzheimer's

I discharged my duties as carer with mixed results. We played ball in the kitchen and broke a glass. We started a walk and then abandoned it.

Some of the time, she was baffled as to who I was and exactly what I was doing in the house. But along the way, we also managed to enjoy ourselves, listening to music, eating lunch together, looking at photos, and indeed chuckling together over the minor calamities that befell us.

When John returned and relieved me of my position, I asked him how much of Nancy he thought was left. He answered in the spirit of the engineer he'd been, with an exact number.

"Thirty per cent," he said, and then he tapped his head, and said that the rest was still preserved safely in his memory.

It was an oddly romantic moment.

The ravages of dementia can be unbelievably upsetting to see. No one would wish the confusion and forgetfulness that goes along with the disease on another person - though sadly, for demographic reasons, they are likely to be an ever-increasing part of our lives.

But my stay in Phoenix also taught me to be mindful of certain positives.

However much is taken by dementia, something always remains. There can still be a person beyond their words and their memories, a spirit, for want of a better word, and a continuity with the person they were.

Faced with the disease, and with the right support, most people can learn and adapt, finding new ways to love their parents and partners.