Should people accept that pressure is a fact of life?

- Published

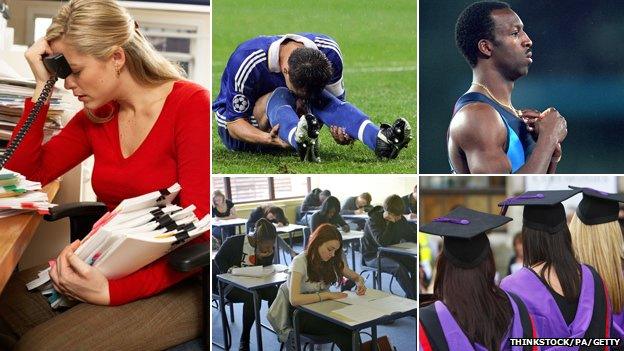

For thousands of youngsters, crucial exams are nigh. Many say the pressure on students should be minimised, but should people just accept it as a fact of life, asks Matthew Syed.

Is it any wonder that many students fail to perform, not because they lack ability, but because of the unique pressure of the exam room - the ticking clock on the wall, invigilators pacing up and down, and the surreal sense that one's very future is in the balance?

We are competitive animals and, however we decide to evaluate each other - whether at exams, job interviews or even on romantic dates - we are occasionally going to get nervous. Removing pressure altogether from life is, in many ways, an impossible dream.

A <link> <caption>new test</caption> <url href="https://ssl.bbc.co.uk/labuk/experiments/compete/" platform="highweb"/> </link> about the psychology of pressure, devised by the BBC's Lab UK, will offer a new look at why some people are particularly prone to pressure, while others cope rather well. The scientists want to find out why some people lose control of their emotions, while others stay in control.

It is not just students who face a psychological ordeal this summer. Olympic athletes, too, are about to come face to face with a life-defining moment - and many will struggle to cope.

When I played at the Olympic Games in Sydney as Britain's top table tennis player I was in the form of my life. But when I walked out into the mega-watt light of the competition arena, I could hardly hit the ball. To put it simply, I choked.

Almost all of us know what it is like to choke. Perhaps we froze during finals, or perhaps we got tongue-tied during a hot date, or maybe we just couldn't remember our lines during a big job interview.

Why does it happen? The neuroscience of choking is rather intriguing, and it can best be understood by considering what happens when you are walking along the street.

None of us actually think about the mechanics of how we walk as we are ambling along - we are thinking about what we are going to have for dinner, or what we are going to say at our next meeting, etc.

But now imagine that you are walking along a narrow path with a 10,000 foot precipice on either side. Now, we might think about how we are moving our feet, the angle of our tread, the precise footfall on the path. And this, of course, is when we are most likely to fall.

Walking is, when you think about it, quite a complex set of movements and if we think too much about them we are far more likely to get confused. This, incidentally, is why walking feels so weird when we are in front of a lot of people, like at graduation.

The same thing happens when we get tongue-tied. We are so anxious about saying precisely the right words that, instead of just saying them, we try to say them. We are, in effect, striving too hard.

Instead of using the subconscious part of the brain, which is the most efficient way to deliver a familiar skill (like talking, walking or remembering a maths formula during an A-level), we use the conscious part. And this is when it all goes wrong.

To put it another way, in order to overcome choking we must trust our subconscious competence. And, it turns out that we are far more likely to do so when we are as familiar as possible with the situation we are about to face.

As Sir Clive Woodward, the rugby coach turned Performance Director of Team GB, put it: "It is no good going into a high-pressure environment unsure of what to expect. You need to be on top of everything."

British athletes will have to prepare for all the distractions that occur at a home Olympics

In preparation for the Olympics, athletes will spend as much time as possible getting used to the competition venue - the lighting, feel, and acoustics.

They will also have studied possible opponents and planned a routine for the hours leading up to the contest, so that everything is smooth and calm. By ensuring that they are not assailed by the unexpected, they are less likely to experience stress.

When it comes to exams, the parallels are obvious. Many students are profoundly spooked by working up against a hard deadline - in which case, diligently practising essays or problems under time constraints, perhaps with a parent or friend acting as invigilator, would help dramatically.

Many students complain of running out of steam because of the nervous energy they expend - in which case, taking a banana and a bottle of water would boost mental performance.

Others complain about the noise of invigilators pacing around - in which case a pair of earplugs can help to regain focus. Many students are vexed by the unfamiliar format of an exam paper, or the tone of the questions - in which case deep familiarity with past papers, as well as chief examiners' reports, will work wonders.

All these small things are easy to do, but often forgotten.

Of course, even when we are well prepared, we may still feel terribly nervous - but at least we will be more equipped to deal with our nerves than if we have failed to prepare.

The test is presented by athlete Michael Johnson

Furthermore, we may also benefit from reminding ourselves that the big moment is, from a different perspective, not that big after all.

Even a huge exam is not as important as, say, a loving family, or good health. And even a huge job interview can be put into perspective by looking up at the stars and remembering that it is all rather trivial in the grand scheme of things.

Many athletes attempt to change their frame of reference, in this way, just before big matches. At one competition, I remember hearing an opponent muttering under his breath: "It is only bloody ping pong!."

It seemed to calm him. He defeated me by three games to one.

Pressure is an integral part of life, of course, and sometimes we are going to stumble.

But so long as we remember to trust our subconscious competence, and, where appropriate, to alter our frame of reference, we will already be half way to defeating the curse of choking.

<bold>Matthew Syed is the author of Bounce: The Myth of Talent and the Power of Practice.</bold>