Who, What, Why: How much rain is needed to ease the drought?

- Published

It has been the wettest April in the UK since records began in 1910, with flood alerts and warnings in place across England and Wales. Why then are parts of the country still officially in drought and why is the hosepipe ban set to remain?

People have long spoken of April showers, but the likes of last month's heavy rain and storms haven't been seen in more than 100 years. The heavens opened just as hosepipe bans were introduced and a number of regions were officially declared to be in drought.

While the long, persistent rainfall has provided relief for farmers, gardeners and wildlife in drought areas, experts say it will take more than one wet month to make up for many dry ones.

According to John Rodda, a water consultant and former head of the World Meteorological Association, in the 12 months to March, about 40% less rainfall than average was recorded. This means, he says, that there was a shortfall of about 120mm.

.gif)

April’s heavy rain runs against the long-term trend for southern England

As a result, groundwater levels are at a historic low. But experts say the rain has come at the wrong time of the year for these stocks to be easily replenished.

Provisional Met Office data up to 29 April showed 121.8mm (4.8in) of rain fell on average, almost double the long-term average for April of 69.6mm.

Aerial images of Bewl Water, in Kent, show the reservoir about 50% full when it should be about 90%. Water companies say the recent rain is not enough to replenish reservoirs, rivers and underground aquifers.

At ground level the difference is clear. This photo shows Bewl Water 80% full in 2006. Rainfall received during the last two winters is the lowest recorded in the past 100 years for consecutive winters.

By December 2011 the reservoir was 45% full. Eleven out of the last 18 months have had below average rainfall. Only sustained periods of rain will significantly help increase water levels.

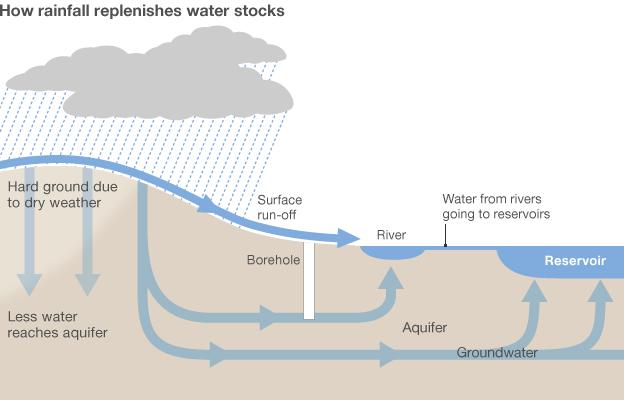

But Jamie Hannaford from the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology says we need rain in winter rather than summer. "It's in the winter season that the rain that falls can soak down through the soil and make its way down into the groundwater stores.

"We really need not just above average rainfall. We would need exceptional rainfall to change the situation."

<link> <caption>According to the Met Office</caption> <url href="http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/averages/19712000/areal/uk.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> , average rainfall is much higher in December than April or May.

But the rainfall in winter replenishes stocks much more as the evaporation is low. Evaporation increases substantially over the summer, so aquifers - underground natural reservoirs formed from porous rocks - are recharged mainly during October to March.

The soil at the surface needs to be "wetted up" in order to allow rainfall to move down through the underlying rock material into the aquifer.

Evaporation rates vary according to factors such as vegetation and soil type.

"It will take a much longer period of sustained rainfall for the groundwater to recover in chalk, which is the UK's primary aquifer," says Dr Adrian Butler, a reader in subsurface hydrology at Imperial College London.

"One of the main reasons for concerns over water availability in southern and eastern England and the Midlands - which are officially in drought - is their dependence on groundwater from aquifers.

"Weeks of rain are needed to wet the ground enough for rainwater to percolate down and begin filling up the aquifer. After the wettest April on record, this is starting to happen. However, most of rain in recent weeks has run off directly into rivers, which is why we are experiencing flooding in some places at the moment."

Butler estimates that water levels in those areas are around 10m below average for this time of year.

"Crudely, the amount of water needed to 'fill' or saturate the rock - usually chalk - is about 1% of its total volume, therefore to raise the water table by 10m requires approximately 100mm of water. However, you need to take into account as the weather warms up, water evaporates more readily from the soil," he says.

In addition, removal of groundwater and flows to springs and rivers over the summer need to be taken into account, he says. These can be estimated as being approximately equivalent to a reduction of 5m in the water table or around 50mm rainfall.

Because the ground at the end of March was so dry, around 30-70mm of water would have been needed to wet it up before recharge can take place.

A complicating factor, he says, is that rainfall rates are very variable and intense rainfalls, such as we can get during summer storms, results in a fraction of the rainfall flowing rapidly into rivers without going into the groundwater system.

"If we take a value for evaporation over the period April to September in the South East to be around 450mm - a very approximate figure as it depends on the type of weather we have - then, very crudely, we can say that to bring groundwater levels back to normal we need at least 50 mm (wetting up soil), plus 100mm (net increase in aquifer storage), plus 50mm (losses from aquifer over summer), plus 450mm (losses due to evaporation) over the next six months."

This gives a total of 650mm, Butler says.

"However, taking into account the fast run-off effect means that we could need about 10% more, or approximately 50mm or so, making a grand total of around <bold>700mm</bold> between April and September. As the rainfall for southern England during this period is around 60mm per month (for example around 350mm over the next six months), we're therefore looking at needing about twice the normal amount of summer rainfall."

While these figures focus only on one drought-stricken region of the UK, they highlight the difficulty of trying to determine how much rainfall is needed to alleviate drought conditions.

As a result, water companies are warning customers that a hosepipe ban is likely to remain in place for some time to come.