Leonardo da Vinci: How accurate were his anatomy drawings?

- Published

Martin Clayton, senior curator of the Royal Collection, shows Fergus Walsh some of the exhibition highlights

The largest exhibition of Leonardo da Vinci's drawings of the human body goes on display in the Queen's Gallery at Buckingham Palace this week. So how accurate were they?

During his lifetime, Leonardo made thousands of pages of notes and drawings on the human body.

He wanted to understand how the body was composed and how it worked. But at his death in 1519, his great treatise on the body was incomplete and his scientific papers were unpublished.

Based on what survives, clinical anatomists believe that Leonardo's anatomical work was hundreds of years ahead of its time, and in some respects it can still help us understand the body today.

So how do these drawings, sketched more than 500 years ago, compare to what digital imaging technology can tell us today?

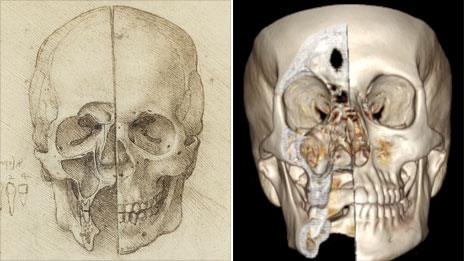

The skull

pics courtesy of Royal Collection and radiologist Dr Richard Wellings, UHCW

From a notebook dated 1489, there is a series of meticulous drawings of the skull.

Leonardo has cut off the front of the face to show what lies beneath. It is difficult to cut these bones without damaging them. And elsewhere in his papers, Leonardo left a drawing of the knives he used.

According to Peter Abrahams, professor of clinical anatomy at Warwick University in the UK, Leonardo's image is as accurate as anything that can be produced by scientific artists working today.

"If you actually know your anatomy, you can see all the tiny little holes that are in the skull," says Prof Abrahams.

"Those are absolutely anatomically correct. Leonardo was a meticulous observer, and a meticulous experimental scientist. He drew what he saw, and he had the ability to draw what he saw absolutely perfectly."

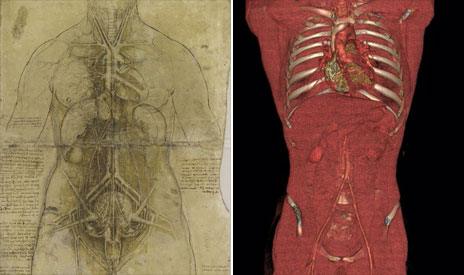

The torso

pics courtesy of Royal Collection and radiologist Dr Richard Wellings, UHCW

According to Prof Abrahams the upper half of the drawing of a torso is a fairly accurate observation of the body. The liver, for example, is correctly placed not far below the woman's right breast. Its size suggests that the woman may have suffered from liver disease.

The problems with the image start lower down, however. Clinical anatomist Prof Abrahams says that the uterus is wrong. This image, he suggests, is reminiscent of what we see in animals such as cows.

It is possible that given the difficulty of getting hold of female corpses, Leonardo used the knowledge that he had gained from dissecting animals to help him understand the human body.

On the right arm, there is a finger print which has smudged the line of the drawing. It could very well be Leonardo's own.

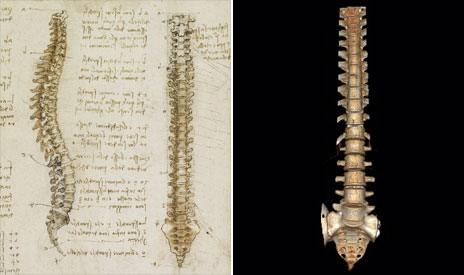

The spine

pics courtesy of Royal Collection and radiologist Dr Richard Wellings, UHCW

The spinal column shown here is thought to be the first accurate depiction in history.

According to Peter Abrahams, Leonardo perfectly captured the delicate curve and tilt of the spine, and the snug fit of one vertebra into another.

This drawing by itself would have secured Leonardo a place in history. As far as two-dimensional images go, it is as good as anything produced today.

But it is just one of a series of drawings in which he pushed forward the frontiers of science. He dissected and wrote up his investigations into every bone in the human body, except the skull.

Professor Abrahams suggests that it was Leonardo's skill as an architect and engineer that gave him the insight in to how the body actually works.

"This mechanistic approach, this engineering-approach, has only become really popular in the field of surgery within the last 50 or 60 years," says Peter Abrahams.

"There are still many people doing research on all these little ligaments and pulleys to this very day all over the world."

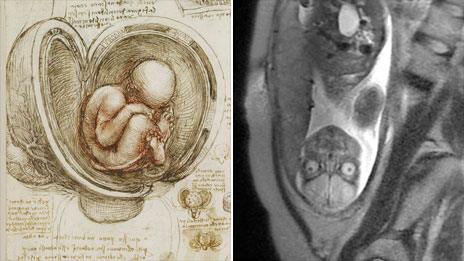

The embryo

pics courtesy of Royal Collection and radiologist Dr Richard Wellings, UCHW

Despite his desire to draw the body accurately, Leonardo was still wedded to certain ideas that he had inherited from the Middle Ages. He still, for instance, thought of the human reproductive system as in some way analogous to that of plants.

"All seeds have an umbilical cord which is broken when the seed is ripe," writes Leonardo. "Likewise they have a uterus and membranes, as herbs and all seeds that are produced in pods demonstrate."

Below his embryo, Leonardo sketched the uterus opening like the petals of a flower.

When he died, the treatise he planned to write was left incomplete. His detailed drawings were left to his assistant Francesco Melzi. Ground-breaking observations including the flow of blood in to the heart were lost to science.

Anatomists such as Prof Peter Abrahams believe that Leonardo's work was some 300 years ahead of its time, and in some ways superior to what was available in the 19th Century Gray's Anatomy.

They say it is only recently with 3D, digital technology and moving images that we have been able to take a decisive step beyond what Leonardo's hand and eye were able to achieve.